200 Years after His Death, Paris Invites Its Most Divine Debaucher to Sully Its Art Halls

‘Sade. Attacking the Sun’ at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (photograph by Nicolas Krief, all images courtesy Musée d’Orsay)

‘Sade. Attacking the Sun’ at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (photograph by Nicolas Krief, all images courtesy Musée d’Orsay)

Encouraged by the turnout at last year’s blockbuster collection of male nudes, Masculine, the Musée d’Orsay has whipped up a guaranteed succès de scandale with its bicentenary tribute to the Marquis de Sade, whose death anniversary was yesterday: December 2, 1814.

The scandal over Sade. Attacking the Sun set in before anyone had a chance to see what’s hanging on the walls, thanks to a racy publicity video on YouTube that many have decried as unbefitting Paris’ most revered masterpiece-repository after the Louvre. In the clip, dozens of naked bodies writhe together to spell out the name Sade, the frequently imprisoned writer, divine debaucher, and one of the dodgiest Frenchman who ever lived, who gave us The 120 Days of Sodom and the term “sadism.”

This provocative exhibition traces the impact of Sade’s banned writings through more than two centuries of art and literature. Although rarely so openly acknowledged for sparking a revolution in 19th-century thought, he liberated perceptions and portrayals of our bodies, sexuality, desire, violence and base human instinct.

Powerful stuff, even if most people will just come to the Orsay to point at the naughty bits. I went along with a young French couple and their three-month-old son. Papa didn’t want baby’s first exhibition to be a corrupting force, so he pushed the pram back to the safety of the Impressionists’ wing. Squeamish and prudish visitors may want to follow suit, but let’s head straight into the bowels of the beast.

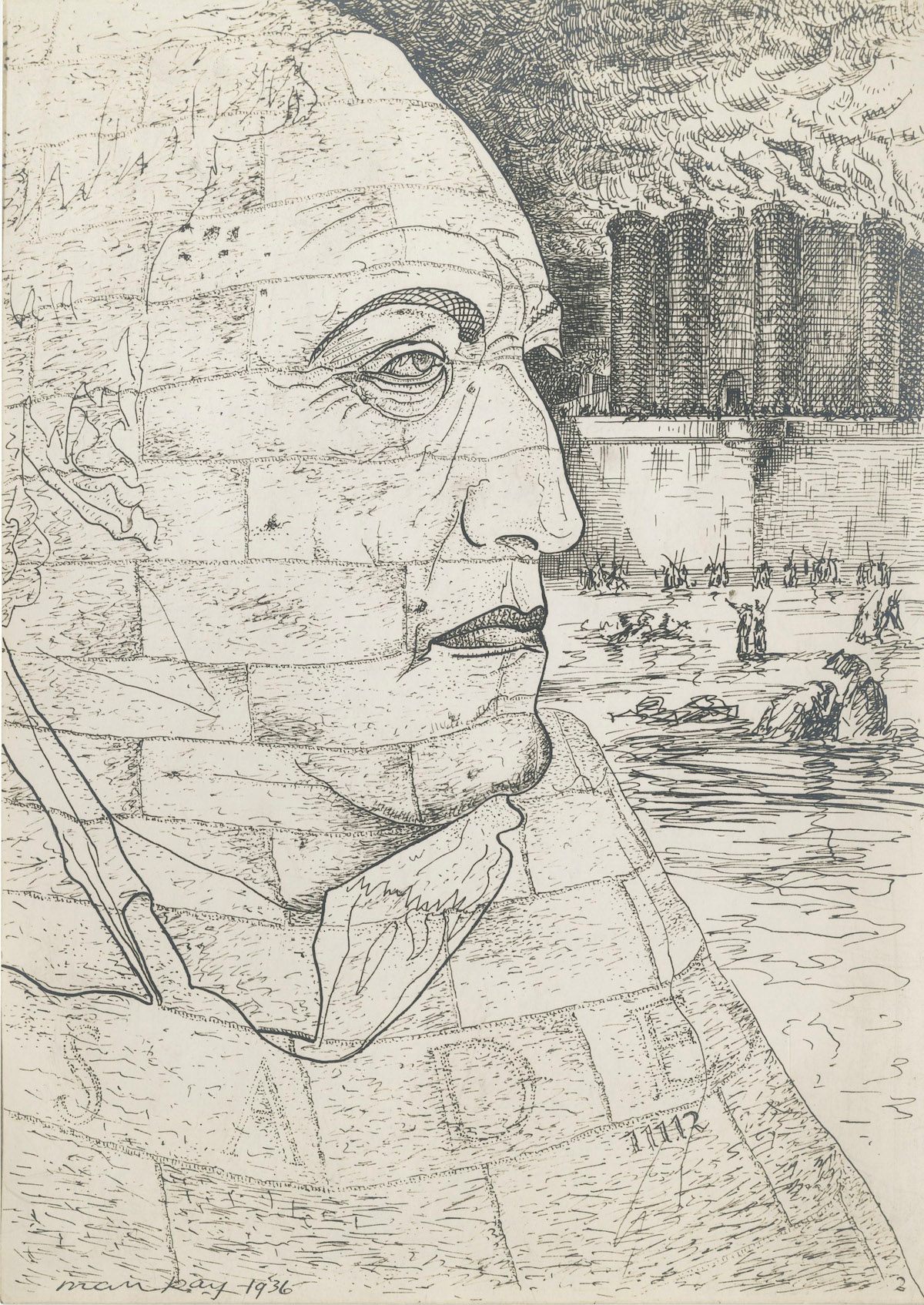

Man Ray, ”Portrait of the Marquis de Sade” (1936) (Art Institute of Chicago, © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP)

Man Ray, ”Portrait of the Marquis de Sade” (1936) (Art Institute of Chicago, © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP)

The Marquis himself is just a starting point in this wide-ranging exhibition curated by Sade specialist Annie Le Brun. The potency of his words jumps out as us from the walls where some of the juiciest quotations have been scrawled, along with snippets by other French 19th-century authors who seized on the same ideas. There are rare illustrations from banned editions, by André Masson among others, and an astonishing surrealist caricature of Sade by Man Ray. That Paris-dwelling American artist is beloved for his brand of iconic eroticism in black-and-white prints, but certainly less familiar is his explicit fetish photography.

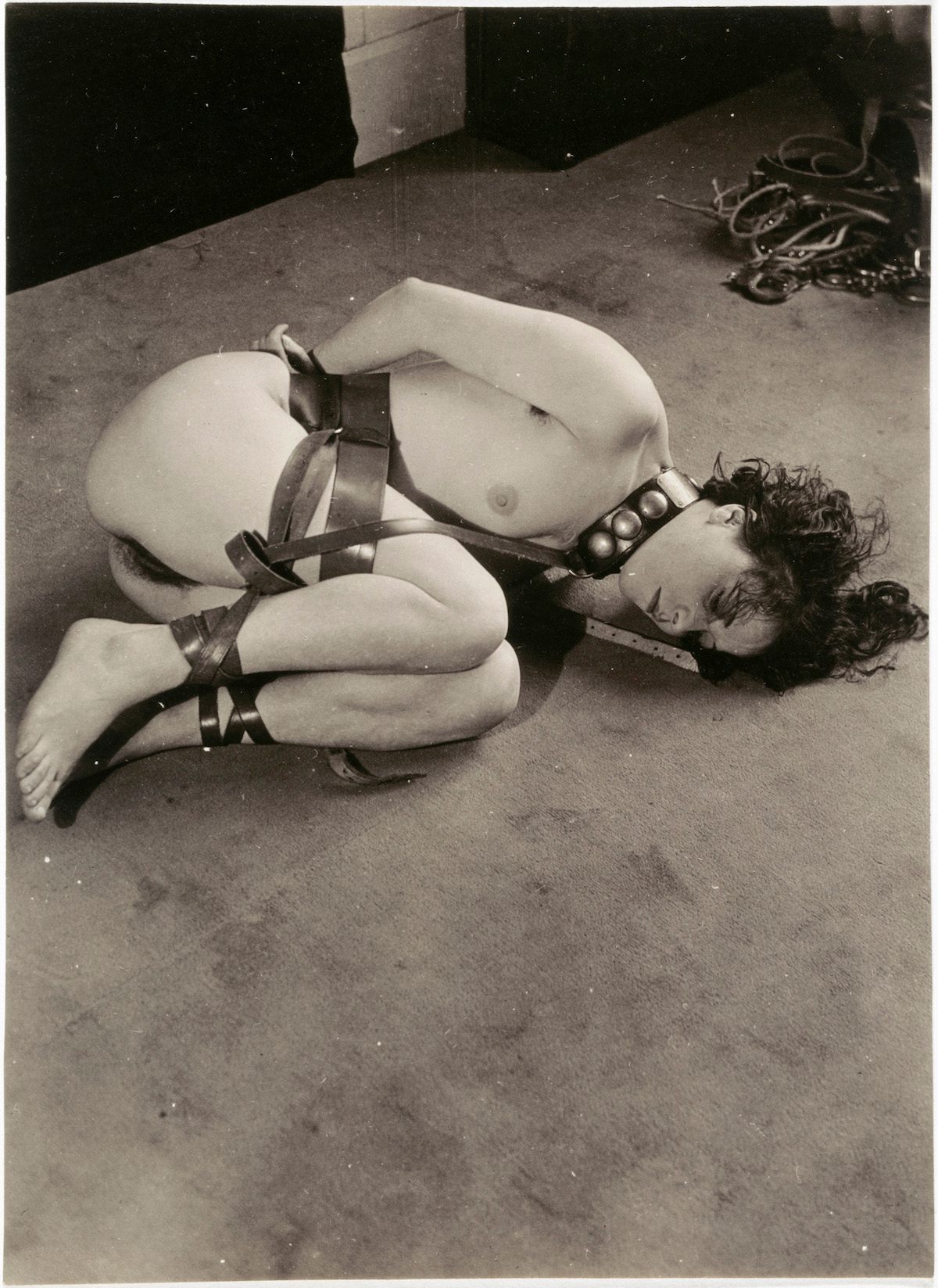

This side of Man Ray is exposed in stark portraits — a naked female model bound in leather straps and dog collar, prostrate on the ground under the inescapable gaze of the lens (“Nu attaché,” 1930) — and in a series of six vignettes posing two wooden articulated artist’s mannequins in flagrante (innocently titled “Mr and Mrs Woodman,” 1927). This last piece is somewhat less flexible than what you’ll find in the Kama Sutra exhibition running concurrently at the Pinacothèque.

Man Ray, ”Nu attaché” (1930) (Centre Pompidou, © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP)

Man Ray, ”Nu attaché” (1930) (Centre Pompidou, © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP)

All a bit tame so far, really. What, no viscera? Our good Marquis mused long and languorously over pain, cruelty, and ferocity as by-products or even complementary states of carnal passion, exhorting us to strip away corporeal limitations as a snake sheds its skin. To inflict pain as much as to endure it, however, one must first understand the body.

To that end, a room of the exhibition is given over to 18th-century specimens of the hyper-detailed wax anatomical figures that fascinated Sade, including some particularly unsettling examples by Honoré Fragonard. Jacques-Fabien Gautier-D’Agoty’s 1754 model dominates the space: a pregnant woman, cut open and splayed out, entrails and fetus ready for inspection. Must have missed that one at Madame Tussaud’s. Rather tongue-in-cheek on the wall (not literally, I should point out) is, as Balzac quipped in 1829: “A man shouldn’t get married without having dissected at least one woman and studied her anatomy.” Meanwhile, a well-chosen Baudelaire observation likens the act of lovemaking to torture or surgery.

Sade’s “no pain, no gain” policy finds expression in images and objects that demand our unflinching voyeurism, and even compliance. One photograph circa 1900 depicts a young woman, legs bound to a chair, receiving from her matronly punisher a brutal nipple-twist with metal pincers. Goya’s most sickening portrayals of so-called inhumane torture, rape, and cannibalism, also get a look-in.

‘Sade. Attacking the Sun’ at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (photograph by Nicolas Krief)

‘Sade. Attacking the Sun’ at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (photograph by Nicolas Krief)

Everywhere there are reminders of man’s bestial nature, including Picasso’s rarely-exhibited doodles of a reclining nude pleasured by a cunnilingus-trained fish; Klemm’s ink drawing of a woman and leopard grappling in 69, undoubtedly the most lovable exhibit; and Jean Benoît’s 1965 bondage sculpture of the sexually depraved, bloodthirsty bulldog from Isidore Ducasse Lautréamont’s 1869 prose poem Les Chants de Maldoror, decked out in leather, covered in broken-glass spikes and equipped with a life-size human penis.

Tackling religion is a must, since Sade’s stance on the Church was a major factor in why he was always evading imprisonment, reveling in acts of sexual violence as he decried the very belief system that would condemn him for it: “The idea of God is the sole wrong for which I cannot forgive mankind.” Within these walls we find scenes of papal rape, cavorting nuns, and a photograph of a female S&M offering strapped to a crucifix… The wrong way round. But for me, the theme is most elegantly summarized in Man Ray’s 1930 photograph Prayer.

The exhibition is a little light on Sapphic content: the penis reigns supreme, especially towards the final rooms, by which time it’s all degenerating into something carnivalesque. Engravings of allegorical penises from the 1760s, titillating female acrobats astride the erect members of her two urinating spotters (Carl Schleich’s “Pièce acrobatique,” 1820). Finely wrought pewter phalluses, complete with piston mechanism, marked “providence of widows and nuns,” circa 1800. And my personal favourite: penis phenakistiscopes — colored, patterned discs that spin to form an image, for which no imagination required. Reproductions would have sold like hotcakes at the gift shop.

Maybe not a great first-date exhibition, but definitely a conversation starter.

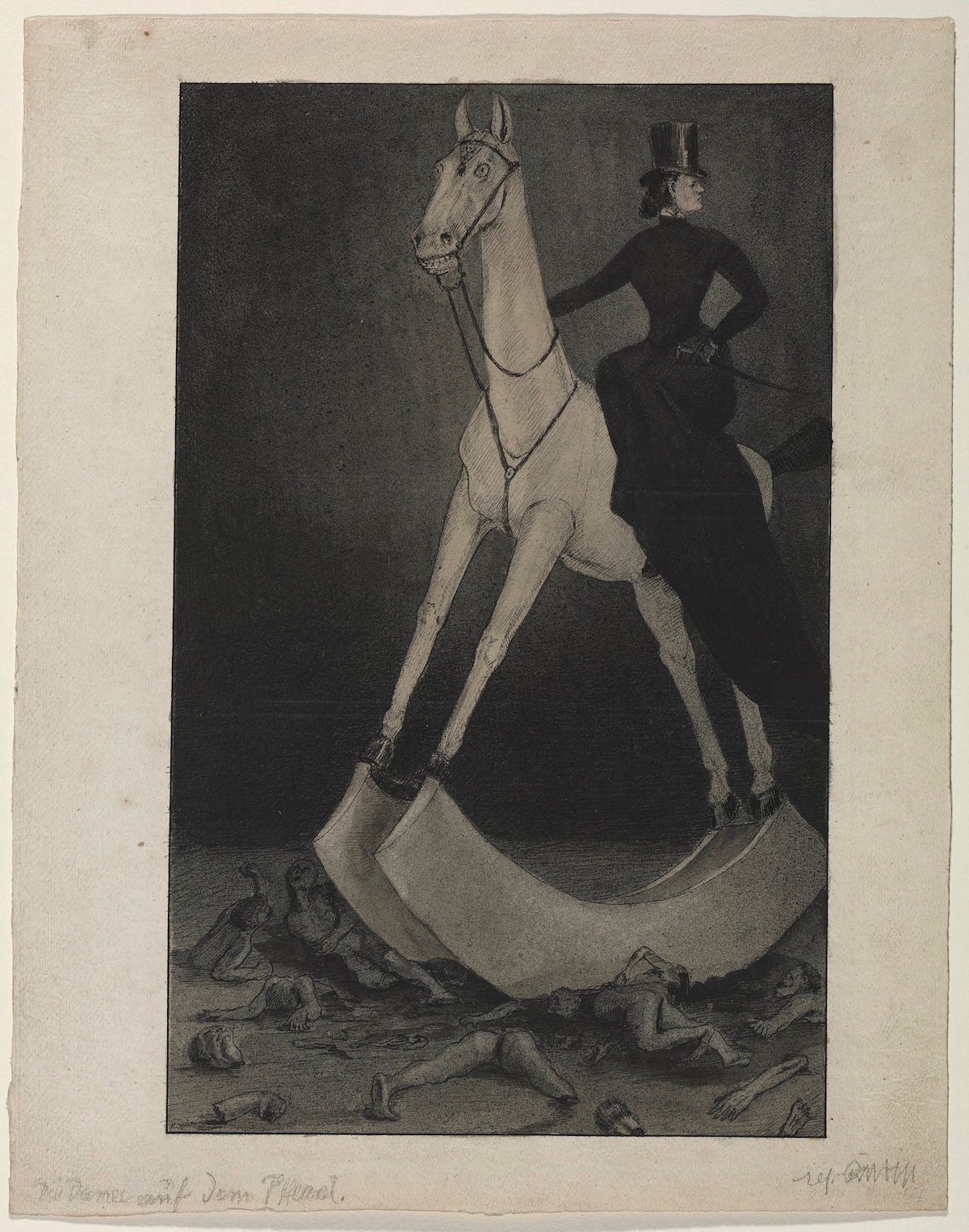

Alfred Kubin, “La Femme à cheval [Die Dame auf dem Pferd]” (1900-1901) (Städtische Galerie, © Eberhard Spangenberg / ADAGP)

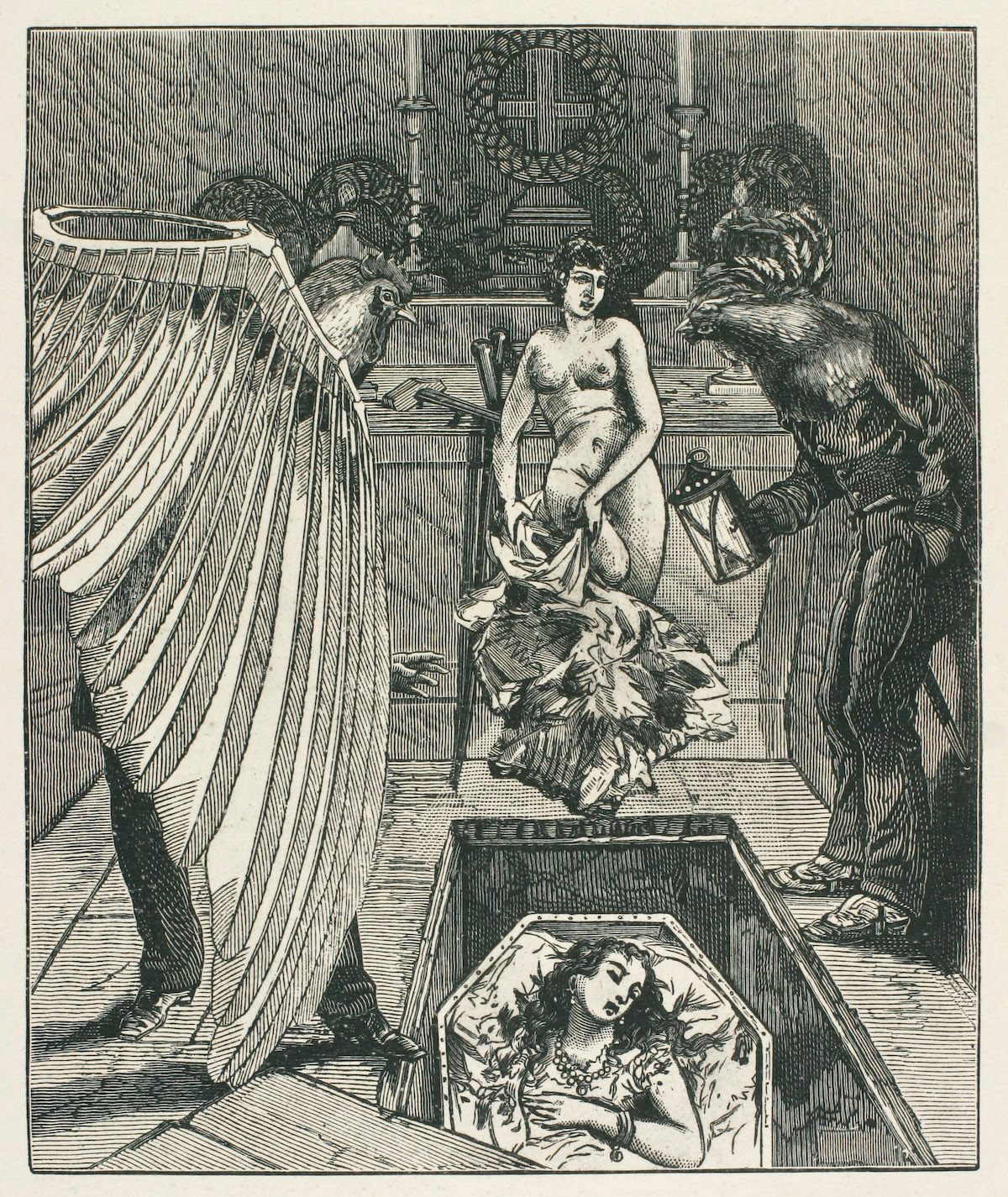

Max Ernst, “Une semaine de bonté ou les Sept Éléments capitaux, le rire du coq,” Édition Jeanne Bucher, Paris, 1934 (© Ubu Gallery, New York & Galerie Berinson, Berlin)

Max Ernst, “Une semaine de bonté ou les Sept Éléments capitaux, le rire du coq,” Édition Jeanne Bucher, Paris, 1934 (© Ubu Gallery, New York & Galerie Berinson, Berlin)

Charles Amédée Philippe van Loo, ”Portrait en buste du jeune marquis de Sade” (1760-1762) (© Photo Thomas Hennocque)

Charles Amédée Philippe van Loo, ”Portrait en buste du jeune marquis de Sade” (1760-1762) (© Photo Thomas Hennocque)

Sade: Attaquer le soleil (Sade. Attacking the Sun) is at the Musée d’Orsay until 25 January, 2015.

Sade fetishists can also see the remarkable 12m-long original manuscript of 120 Days of Sodom at a second Paris exhibition dedicated to the saucy writer: Sade, Marquis of Darkness, Prince of Light at the Institut des Lettres et des Manuscrits.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook