Remembering the Golden Age of Airline Food

Why were in-flight meals so much better in the past?

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE MAY 6, 2023, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

We were 30,000 feet above Utah when I found myself wondering, What the hell happened here? After four hours or so up in the sky, I had cracked and handed over my credit card to purchase food. The “snack pack” that arrived verged on parody: a dozen almonds, a shriveled turkey jerky stick, a bizarre hybrid between a granola bar and a cookie.

Airline food has long been a subject of ridicule, but as of late, it’s gotten downright depressing—especially within the continental United States. From desiccated chicken in questionable cream sauce to pasta lightyears past al dente, I’ve lost track of the number of tragic, bland meals I’ve picked at while flying over the years.

In fairness to the chefs who engineer these meals, the deck is stacked against them. Our ability to taste sweet and salty flavors drops by around 20 percent while flying. And even though airline meals tend to add extra sodium to compensate, it can still feel like you’re eating with your taste buds on mute.

Much of this has to do with the humidity level in an airplane cabin hovering around 12 percent—in the Sahara desert, it’s around 25 percent. Since our noses need moisture to smell properly, that bone-dry air, coupled with a low pressure and a generally stressful environment, is a recipe for disappointment.

And yet, it wasn’t always this way. Once upon a time in the pre-Reagan era, flying in the United States still had a whiff of glamor. In the 1950s, Pan Am passengers in economy dined on stuffed guinea hen, while those in first class enjoyed scoops of caviar and eggs made to order.

Passengers on Trans World Airlines (TWA) once dined on roast beef au jus, carved from a trolley in the aisle. And those on Alaska Airlines toward the tail end of the 1960s might have taken advantage of its Golden Samovar service, an homage to Eastern European culinary culture, complete with dishes such as tartlet Odessa and veal Orloff.

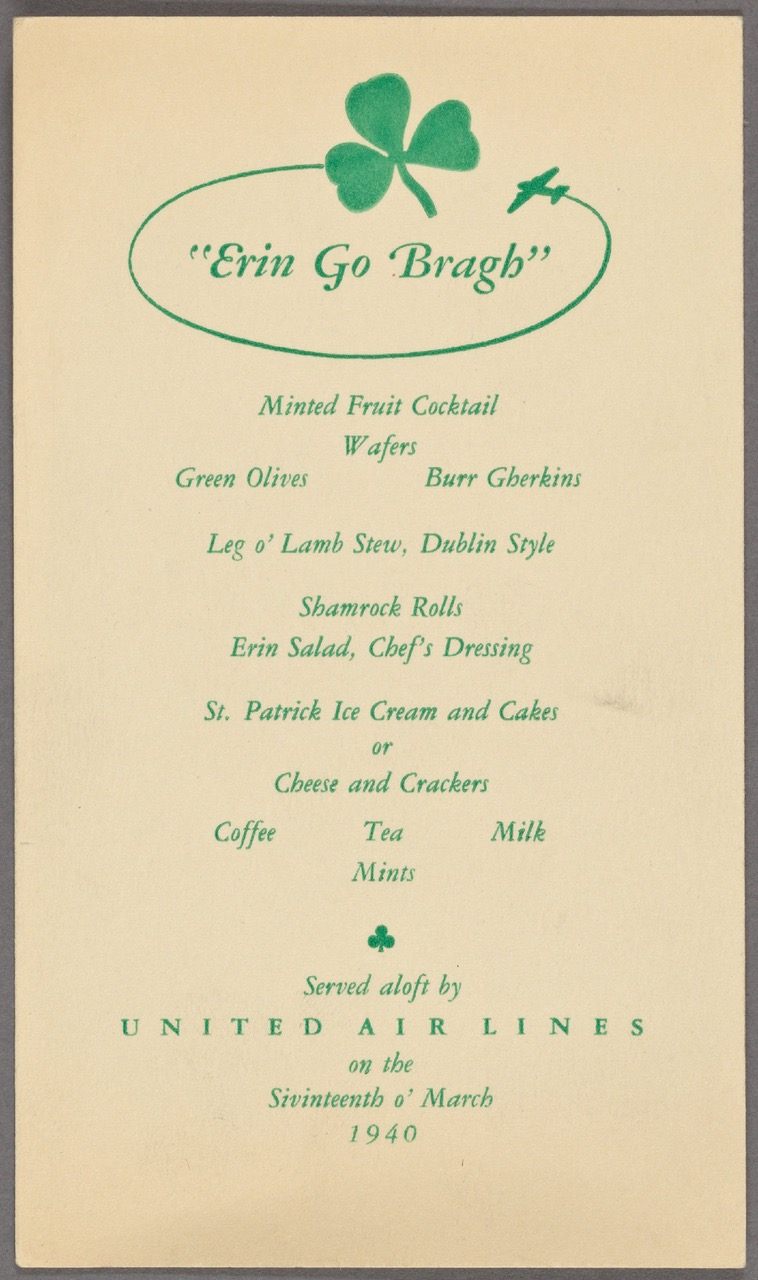

Perhaps most striking of all, United Airlines ran an “Executive” flight exclusively for men between Los Angeles and San Francisco, as well as between Chicago and New York, every weekday at 5 p.m. from 1953 to 1970.

Picture a gentlemen’s club, but with wings. The flight attendants were single and hot, the gin martinis were cold, and your cigar was free. Oh, and of course, “A full-course steak dinner [was] table-served by the two stewardesses aboard.”

While that Don Draper–esque fantasy may be a thing of the past, corporate suits on an expense account still have it pretty good on some flights, particularly once you get away from domestic options. Singapore Airlines, for instance, serves its first- and business-class passengers items such as grilled rib-eye with artichoke-potato hash and black olive chimichurri. Meanwhile, Qantas first-class passengers might dine on a green mango salad with Queensland spanner crab, pork, and cashews in a nam jim dressing.

Still, it’s fun to reminisce about a time when those of us in cattle class didn’t have to subsist on stale Cheez-Its. To get a better picture of the Golden Age of air travel, Gastro Obscura spoke with Richard Foss, author of Food in the Air and Space: The Surprising History of Food and Drink in the Skies.

Q&A With Richard Foss

What were some of the earliest in-flight meals like?

The challenges of cooking in flight dictate the quality of the food. Aboard the zeppelins, they actually had multi-course dinners served in a separate dining room. Now, when you’re in a hydrogen zeppelin, that’s a real bad place to have a barbecue. They wanted a kitchen with no open flame.

So the challenges of cooking in flight started being resolved before the first fixed-wing aircraft. It’s way before induction sources, but they had figured out that if you take a power source and hook it up with a cable, congratulations, you’ve invented the electric oven.

What happens once we start getting to actual airplanes?

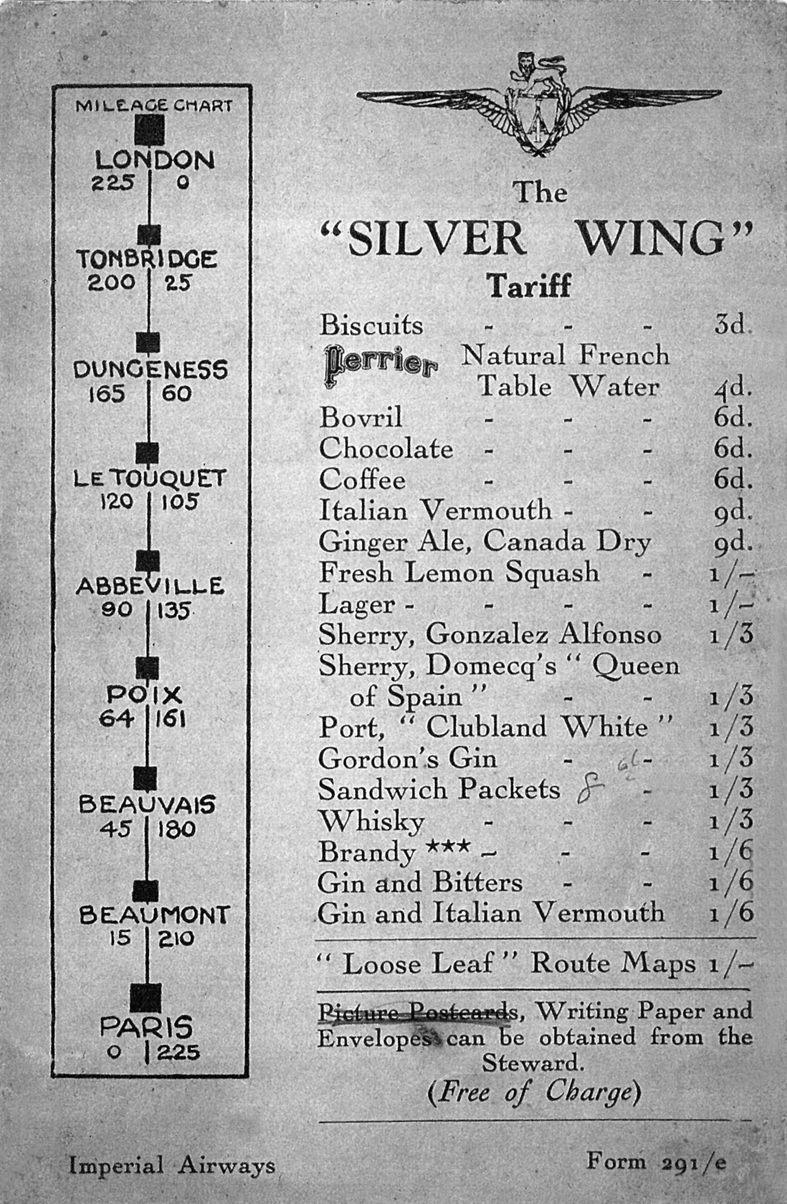

In fixed-wing powered aircraft, the very first meals were sandwiches, coffee, and cocktails on flights between London and Paris. For a very long time, food in those aircraft was very boring because there was no way to heat anything. You would come in with the coffee in a thermos and by the time you drink it, it’s lukewarm.

Aboard what would become United Airlines, the food was monotonous. Stewardesses had instructions to pack the fried chicken, rolls, and salad in separate baskets. It was basically a picnic lunch in the air. The thing is there were no frequent fliers in this era, because travel was extremely expensive. Air travel was done by the elite. Among other things, people were terrified of it.

How’d we get from sandwiches to roast beef dinners here?

War is a spur to technology of all kinds. We think of war as a spur to the technology of killing people, but it is also thanks to war that we get improvements to engines in aircraft and cars. What we think of as the modern airline meal was done as part of a defense contract [for World War II].

An experimenter named William Maxson in Los Angeles invented the convection oven. What Maxson figured out was if you took these little trays in an insulated box and blew hot air over them, you could reheat a whole bunch of things at once.

So if I have roast beef and mashed potatoes and some vegetables, I have to figure out how much I have to cook them in a convection oven at the same time. So they’re all partly cooked, then finished onboard.

Because convection heating is very fast, you have a meal that can be ready very quickly. You just slide 10 or 12 meals into these slots, let them sit in there for a couple of minutes, and slide more in. All of a sudden, you have zero waste and you’re feeding people much more efficiently.

Why exactly were the food options so much better?

Airlines in that era were prohibited from competing on price, so the only way they could compete was on quality of service. You see a slew of advertisements in the 1950s that are about the quality of food on aircraft.

Insofar as there was superior quality, it was often because an airline found themselves with inferior aircraft. So the only way they could get someone to fly them was better food.

United Airlines had the best food in the sky for a while. They put in a huge order of Boeing 247s in the 1930s. After four months, the DC-3 came out, which was bigger and faster. Since they couldn’t just scrap their brand-new aircraft, they were stuck with something smaller and slower. All they could do was get better food.

The same thing happened to Alitalia airlines after World War II. They had these lumbering slow leftover bombers, so they turned them into flying Italian restaurants.

What were some of the other international carriers up to then?

The best food in the air in the 1950s was by Scandinavian Airlines. And the reason was that they were perfectly aware that no one in their right mind would want to visit Stockholm in February. This was an era in which most people needed to change planes. So they had such good food that passengers would fly SAS on their way to Greece or Africa.

The same thing happened in Asia with Singapore Airlines. When Singapore became an independent country, [Singapore’s prime minister] Lee Kuan Yew asked consultants, “Should we have an airline?” and they all said no. But he wanted to be a global business hub. Previously, Singapore had been a relative provincial backwater; it became an international powerhouse. The airline was a big part of that transformation.

What about one of the most important components: booze?

In the early ’30s, a lot of people were terrified of flying and wouldn’t do it unless they were drunk. This was during Prohibition, so the stewardesses were at the ready to confiscate hip flasks. People would have to show their doctor’s prescription so they could get slammed on the plane.

Western Airlines called themselves the “Champagne airline.” Never in their life did they serve a glass of Champagne. They served California sparkling wine. But they still had someone running up and down the aisles pouring it on flights that took 20 minutes, because that was their trademark.

I should also mention the invention of the airline mini-bottle, which was partly a way to make the stewardesses stop stealing the full-size bottles to cater their own parties. There was an airline executive who went to the wedding of one of their own stewardesses and recognized that all the bottles were stolen.

So why is airline food mostly so bleak these days?

There was a cascade of things that happened. Fares had been controlled by the Civil Aeronautics Board, but starting in the 1970s and ’80s, you had airline deregulation by a guy who was an acolyte of Ronald Reagan.

Then once you get frequent flier points, especially for the corporate business people, people are going to stick with their loyalty program no matter what the food is like. Competition becomes much, much less because the most valued customers have those frequent flier programs. You have all the airlines with a race to the bottom, so flying becomes like riding a bus.

The irony is that airline food has gotten fantastically worse as the technology has gotten fantastically better. Airline food in first class is shockingly good because they have learned so much since World War II.

The more horrible you make it to fly coach, the more business people will demand to fly business and first class. The airlines make a bucket of money off people traveling up front, which is why they make coach as oppressive as possible.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook