In Alaska, Birch Syrup Is a Sweet Sign of Breakup Season

The running sap is like a local version of Groundhog Day.

In Alaska, “breakup” is the season that quickly sneaks in between winter and summer. Packed, pristine-white snow loosens and turns into brown slush. Mounds of snow melt until parking lots, over just a few days, turn into lakes. It’s not warm spring weather—it’s just warm enough for the ground to unfreeze and the ice to breakup and melt. Depending on whether you live on the coast or interior, more to the south or more to the north, breakup season can last from ten days to several weeks.

Alaskans feel strongly about breakup. It’s too warm to ski, but too early to fish. Yet, this inter-season limbo of dreary weather accompanies lengthening days, and signals that something better is coming.

One of those signs is a bucket on a birch tree, which collects sap that only begins to run during breakup. Alaskans turn that sap into birch syrup. Less sweet than maple syrup, its flavor notes include coffee and cherry, and it’s used to make chocolate or beer, to marinade fish, and to pour on pancakes. In highly weather-aware Alaska, the appearance of buckets on birch trees functions a bit like Groundhog Day, alerting Alaskans that the fishing and hunting season are not so far off.

In Alaska, foraging isn’t just for foodies. Outside of major cities, the nearest grocery store may be a two-hour plane ride or three-hour drive away, and even big-city grocers struggle to stock produce during the winter, so living off the land is part of everyday conversation. (When I joined the faculty of an Alaskan university, I learned to accept that half of a meeting might be spent discussing our weekend hauls.) The arrival of breakup is an opportunity to fill larders that emptied over the winter, so despite the mud and muck, people pull on their Xtratuf waterproof boots—a staple of commercial fishermen’s uniforms that become ubiquitous during breakup—and gather spruce tips (good for beer, ice cream, and pickling) and nettles (often used similarly to basil, in lasagna and pesto).

While a number of forager favorites can be gathered during breakup, I consider birch sap special because it signals the start of breakup and warmer, longer days. While melting snow can be caused by a quick warm-up, running sap only occurs as breakup starts. As noted by Dr. Janice Dawe, a biologist and founder of OneTree, a forest education and research program in Fairbanks, that’s because “the way plants and animals tell time is temperature and light … That’s also why birch trees know how to start their activities for spring.”

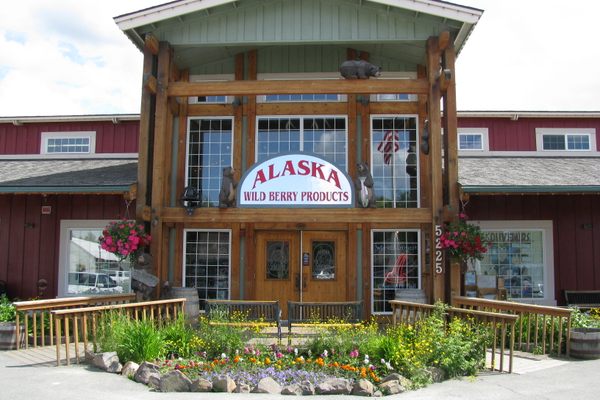

Since birch sap starts flowing through the tree almost exactly when breakup begins, the weather that tappers face is terrible. “It’s the worst possible conditions … it’s really hard,” says Dulce Ben-East, owner and general manager of Alaska Wild Harvest. After a tree has been tapped, by the time a sap-filled bucket needs to be picked up the next day, the ground may have already become hard-to-traverse mush overnight.

At Alaska Wild Harvest, they start looking for signs in their 11,000 trees in March or April, tapping several dozen in different areas in search of running sap. The actual tapping—placing a spigot and bucket—isn’t complicated or expensive, but timing is key. If the trees are tapped too early, they can dry-up and not run at all. If temperatures rise into the 50s before the sap run is over, the sap can spoil before it’s processed. For Ben-East, knowing when to tap is instinctual now. “It’s in the air; it’s breakup. The snow is rotting, the ground is yuck, and we have to transition from snow machines to four-wheelers to get to the fields.”

Processing the sap is tricky and time consuming too. The reverse-osmosis process of removing excess water takes several hours, and making one gallon of syrup requires boiling down nearly 100 gallons of raw, easily scorched birch sap (compared to only 40 gallons of maple sap).

As a result, only a modest number of individuals tap their own trees. Tom Barrett, a resident of Anchorage, began tapping three years ago after visiting a booth from Alaska Wild Harvest at a market north of Anchorage. Barrett, who is an avid skier, talks about break-up as a bittersweet time of year and even has a mantra: “When skiing going mushy, it’s time to make the slushy.” Birch slushy, that is. “It fills a void in my life … the afternoons are warm and the ground is mush. It’s a great time to just hang out inside and process some syrup.” Working with three taps in his own backyard, Barrett collects enough sap for about three small containers of syrup.

While not every Alaskan forages for birch sap, awareness of sap starting to run is still high. Personally, I always see the buckets out, or hear within a day or so from a coworker or the radio. This is just one example of residents’ awareness of weather and seasons: Local public radio often announces how many minutes of daylight we gained or lost each day, and an annual competition called the Nenana Ice Classic offers hundreds of thousands of dollars in prize money to whoever best guesses the exact second when the Tanana River’s ice breaks up.

And, of course, Alaskans who don’t tap birch trees can still get syrup from a store or a friend’s homemade haul. While home cooks have long slathered birch syrup on pan-fried cod and dressed salads with it, birch tapping is also a growing practice, both commercially and among foragers. Ben-East says she started tapping trees 30 years ago to address food insecurity by “utilizing an abundant resource that [we] could produce in Alaska, and not import from out of state.” Similarly, Dr. Dawe’s OneTree program runs a cooperative that encourages people to bring birch sap from their trees to be processed into syrup. “There is nothing like the gratitude you get when you are tapping a tree and you get something so delicious,” she says. “You can just tap one tree and get excited about it.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook