Remembering When America Banned Sliced Bread

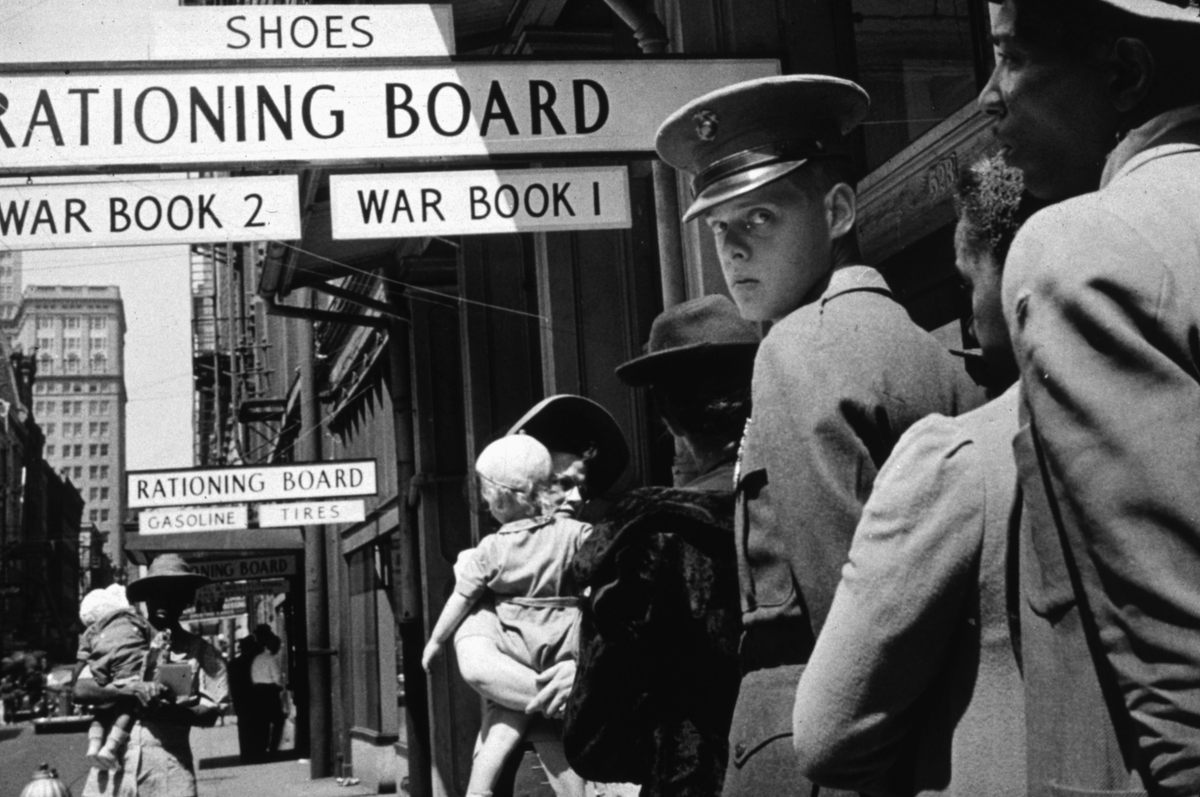

During World War II, the U.S. government turned to drastic rationing measures.

The year was 1943, and Americans were in crisis. Across the Atlantic, war with Germany was raging. On the home front, homemakers were facing a very different sort of challenge: a nationwide ban on sliced bread.

“To U.S. housewives it was almost as bad as gas rationing—and a whale of a lot more trouble,” announced Time magazine on February 1, 1943. The article goes on to describe women fumbling with their grandmothers’ antiquated serrated knives. “Then came grief, cussing, lopsided slices which even the toaster refused, often a mad dash to the corner bakery for rolls. But most housewives sawed, grimly on—this war was getting pretty awful.”

The ban on sliced bread was just one of many resource-conserving campaigns during World War II. In May 1942, Americans received their first ration booklets and, within the year, commodities ranging from rubber tires to sugar were in short supply. Housewives, many of whom were also holding down demanding jobs to keep the labor force from collapsing, had to get creative. When the government rationed nylon, women resorted to drawing faux-nylon stockings using eyebrow pencils and when sugar and butter became scarce, they baked “victory cakes” sweetened with boiled raisins or whatever else was available.

So by January 18, 1943, when Claude R. Wickard, the secretary of agriculture and head of the War Foods Administration, declared the selling of sliced bread illegal, patience was already running thin. Since sliced bread required thicker wrapping to stay fresh, Wickard reasoned that the move would save wax paper, not to mention tons of alloyed steel used to make bread-slicing machines.

Although Americans railed against the idea of living without sliced bread, only a decade earlier, it had been something of a novelty. Otto Frederick Rohwedder created the prototype for an automatic bread-slicing machine in 1912. After a fire in 1917 demolished both his machine and all of the work surrounding it, Rohwedder had to start over almost from scratch.

On July 7, 1928, the Chillicothe Baking Company in Missouri first put his invention to use, saying it was “the greatest forward step in the baking industry since bread was wrapped.” The front page of the local paper, the Constitution Tribune, proudly announced that “Sliced Bread Is Made Here.” “The idea of sliced bread may be startling to some people,” continued the article. “Certainly it represents a definite departure from the usual manner of supplying the consumer with baked loaves.”

Sliced bread really took off in 1930, when the Continental Baking Company’s pre-sliced Wonder Bread made its way into American homes. After a few years of aggressive marketing, the pillowy, preservative-laced loaves were synonymous with modernity and convenience. Consumers had no desire to give them up.

The backlash to the ban on sliced bread was immediate. “I should like to let you know how important sliced bread is to the morale and saneness of a household,” wrote an indignant Sue Forrester from Fairfield, Connecticut, in a letter to the editor of The New York Times. “My husband and four children are all in a rush before, during and after breakfast. Without ready-sliced bread I must do the slicing for toast—two pieces for each—that’s ten. For their lunches I must cut by hand at least twenty slices, for two sandwiches apiece. Afterward, I make my own toast. Twenty-two slices of bread to be cut in a hurry.”

On January 24, less than a week after the ban, the whole thing began to unravel. New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia made a public announcement that bakeries that already had bread-slicing machines could carry on using them. Needless to say, this caused a rift between those bakers with slicing machines and those without. One baker by the name of Fink, who also happened to be a member of the New York City Bakers Advisory Committee, publicly advocated for the ban, then was fined $1,000 (more than $14,000 today) for sneakily violating it.

By March 8, the government decided to abandon the wildly unpopular measure. “Housewives who have risked thumbs and tempers slicing bread at home for nearly two months will find sliced loaves back on the grocery store shelves tomorrow in most places,” noted the Associated Press. Wickard refused to acknowledge the ire of both housewives and bakers, saying simply that the savings were less than anticipated and that it turned out there was enough wax paper to go around after all.

In the end, no thumbs were severed and Americans were reunited with the sliced bread they had learned to hold so dear. When the 1950s rolled around, consumers were eating six slices of industrially produced bread a day, and the nationwide ban was little more than a quirky anecdote about the bizarre indignities of wartime rationing.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook