Learning About Cities by Mapping Their Smells

The U.K. artist Kate McLean is trying to preserve our olfactory memory.

Each of us probably has one: a scent that, as soon as we step out of a car, bus, or train, immediately reminds us that we have made it back home. But what happens when that smell isn’t there anymore? How would you describe it to people that never had any experience of it?

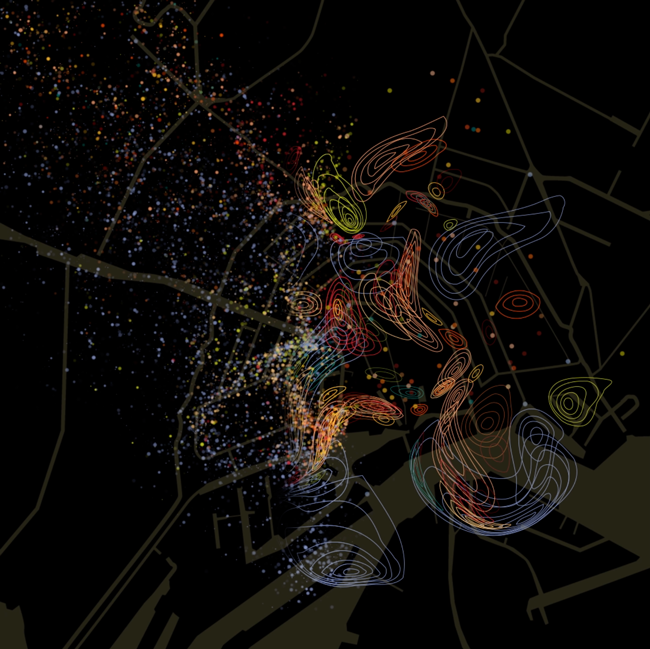

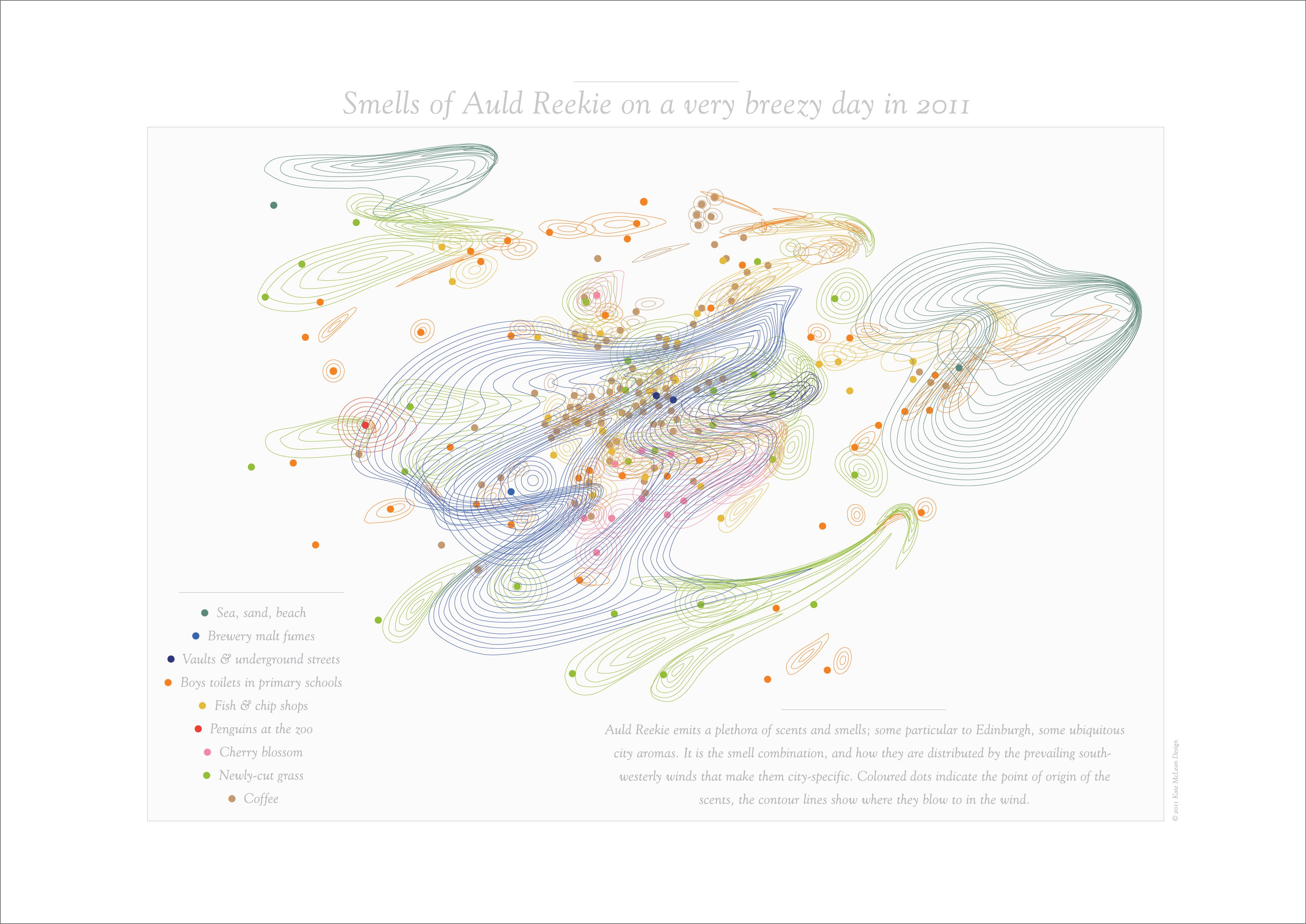

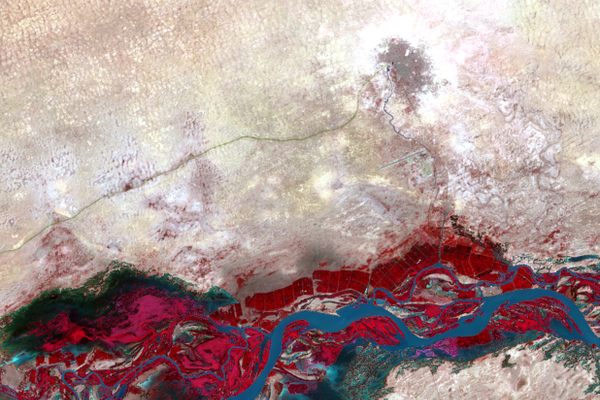

The artist Kate McLean has been trying to address these and other questions for the past seven years with her Sensory Maps project. In 2010, she began looking for ways to map landscapes based on sensory input. The first of these maps related to smell. “I collected comments about smell from people in different parts of Edinburgh,” she says, “and transformed that into a visualization that had this amazing link to the environment, as smell often has to do with conditions like wind direction, rain, or changes in temperature.”

McLean calls such a visualization a “smellmap.” Smellmaps can come in handy for people interested in new ways of exploring both the cities they live in and the ones they visit. So far, McLean has led small armies of urban explorers on “smellwalks” around 12 other cities, including New York, Singapore, Barcelona, and Kiev. Participants are provided with a smell visualization kit, replete with scoring cards and colored pens, that helps them log odors as they walk. After cataloging each scent, the smellwalkers also evaluate some of its attributes, such as intensity, pleasantness, and familiarity. They then mark their findings on white canvasses, which McLean later turns into beautiful visualizations.

A smellmap, made up of colored spots and concentric lines that look like galaxies, is a visual synthesis of the different experiences reported by smellwalkers, explains McLean. “It’s very unlikely that two people standing in the same place would smell the same exact scent,” she says. “So rather than seeking precise definitions and classifications, the way classic scientific cartography does, I am interested in negotiating different perceptions.”

As McLean explains, negotiation is not just about averaging out how many times people wrote “coffee” in their report cards. Often, it is about finding common ground regarding what is evoked by a particular scent in a particular context.

During a smellwalk in Brooklyn, one of her participants reported the “smell of shattered dreams.” McLean asked each person in the group what that meant and eventually a consensus was reached. “We agreed that the ‘smell of shattered dreams’ is the smell of walking out of a bar, with that typical stench of beer and cigarettes, and going home alone again.”

But McLean’s work is also about disagreement. She is currently developing a smellscape app, which will be designed so that users can easily contest scents that have been logged by others. “You have to disagree with the map,” she says. “Someone may have logged a smell of ‘bakery,’ but you should feel free to say, ‘well no, now it doesn’t [smell that way].’”

Disagreements about how a place smells can in fact lead to interesting questions about changes in that place’s environmental and social history. “Contested smells should lead us to ask ourselves what it is about cities’ daily routines and rhythms that may be changing? What happened historically?” says McLean.

Often the answer to such questions lies in how human activities are, whether intentionally or not, confined to a particular space. “If we had to walk around a (European) city two hundred years ago there would be many smells we would not be able to recognize” says Professor Jonathan Reinarz, Director of the History of Medicine Unit, University of Birmingham, and author of “Past Scents: Historical Perspective on Smell.” There would be many scents that are now considered rural smells, like cattle or dirt.”

Reinarz says this partly has to do with the industrialization of food production. We no longer need to keep hens in our backyards to have fresh eggs, and many cities now relegate fresh food markets to one common area. But even beyond food, industry has shaped the characteristic odors of our cities and our neighborhoods.

“From pulp and paper towns in Canada, to tobacco-producing regions, or the chocolate scent that still permeates the suburb of Bournville in Birmingham, England, where British chocolate maker Cadbury opened one of its first production sites in 1879, industry can shape people’s identities through their scents,” Reinarz says. “So when they close down or relocate it can be very disorienting for locals.”

Indeed, living in a place that smelled like chocolate for 140 years and waking up one day to realize that smell is gone sounds like a twisted fairy tale. But losing the “smell of home” can be traumatic, whatever the scent.

When McLean asked people what home smelled like, the answers had nothing to do with good or bad scents, but rather with some kind of threshold that signaled a return to a familiar place. “When I asked people in Newport, Rhode Island, the smell of home was ocean based,” she says. “It was about crossing bridges to be able to get to the island. But when I asked people in Ellesmere Port, an industrial city in the north of the U.K., they said that it was the distinctive smell of local industries that, to them, meant home.”

And while photos can help preserve the visual culture tied to an industry, when it comes to smell, we can only rely on stories told by those of us that have been around long enough to remember. But sooner or later, even this kind of shared olfactory memory gets lost.

Throughout history we have long kept official records of many things, from landscapes (maps) to people (censuses) and full moons (almanacs). But olfactory record keeping was never really institutionalized in this way. Historical references to smell often come from non-fiction texts, such as travelogues. One of the first mentions of smell and travel in Western historical literature can be found in Herodotus’s Histories, written in 440 B.C., wherein the Greek writer described the Arabian peninsula as “giving off a scent as sweet as if divine.” But, adopting McLean’s line of thinking, we may ask: What does “divine” mean? Was that how locals perceived their own home smell?

For now, we can’t really answer those questions. But McLean is on a mission to address our historical smell illiteracy. “The goal of my project is to archive smellscapes, to investigate them, to visualize them… to create a sort of Flickr of smells,” she says.

She notes that keeping track of odors through time can also give us insights about social and cultural change. New odors, whether the result of waves of immigration introducing new scents or the evolution of social norms (like those around smoking or changing urban regulations), are often registered as complaints by those that are not familiar with them. “People go, ‘oh, I have never smelled this before, it’s not appropriate,’” says McLean.

“In many communities the introduction of foreign smells can make people very uncomfortable,” Reinarz says, adding that new scents get ranked according to values that may vary significantly across different societies. “In some agricultural communities, the smell of cattle was regarded as a scent associated with wealth. The person smelling of cattle was not ranked any lower—in fact, it was a way to distinguish oneself. But that might not be the same for a urban community.”

Reinarz also explains that smell has long been used as a way to “other” social groups. He cites the case of Samuel Johnson, one of the most prominent English writers of the 18th century and a devout Anglican who famously wrote that he could notice the moment he crossed from England to Scotland by the smell. “Clearly he couldn’t actually do this,” Reinarz says, “but what he was doing was making a very provocative political statement that people have repeated through history whether crossing borders, entering different neighborhoods, or even a restaurant that serves new and unusual cuisine.”

Indeed going for a smellwalk around cities, where scents associated with different cultures get mixed up in the beautiful and complex ways that make up McLean’s maps, can tell us a lot about our unconscious biases. “Smell is often where our hidden prejudices can be found,” McLean says. “But we need a whole new ton of research to unpack this.”

McLean says that one of the things people often report during “smellwalks” is the mismatch between expectation and reality. Her Amsterdam “smellscape,” which will feature in an upcoming exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York City, is one such example.

“People expect Amsterdam to smell primarily of cannabis,” she says. But in her spring 2013 smellwalk, participants recorded the sugary sweetness of waffles, the spices of Asian and Surinamese restaurants, and pickled herring from the markets, which McLean notes is a link to one of the city’s old industries. These food smells were accompanied by the wafting aromas of old books in basement doorways and laundry odors from the city’s house hotels.

Were people bewildered about the wealth of scents captured in the Dutch capital? “Participants are often surprised about how many odors can be detected if you really pay attention to smell,” McLean says. “Humans can differentiate a trillion different smells but we breathe about 24,000 times a day. Much of it can easily go unnoticed.” Unless you map it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook