Once a Boom Town, Now a Ghost Town, Always a Hometown

The Soto family has lived through Arizona’s mining booms and the broken promises that come with them.

This piece was originally published in High Country News and appears here as part of our Climate Desk collaboration.

Centuries-old sycamore trees tower over the dry riverbed of Harshaw Creek, in the Patagonia Mountains of southern Arizona. Where houses once stood, flat, barren earth stretches to the base of nearby low, oak-covered hills. A crumbling wooden building, relic of a mining supervisor’s home, and a cemetery are all that remain of what once was one of the West’s richest mining towns.

Now a ghost town, Harshaw was one of nine mining camps in the area that saw waves of prospectors come and go in the 19th century. It held some of the Arizona Territory’s highest-grade silver, lead, and gold ore, so when the U.S. government passed the General Mining Act in 1872, giving prospectors the right to claim mineral deposits on public land for no more than five dollars per acre, investors poured in. A patchwork of mining claims soon covered the region, with 40 operations in Harshaw alone. Within three decades, the Patagonia Mountains had produced 79 percent of all the ore processed in the territory, with a total value exceeding $2.5 trillion yearly in today’s currency.

With the mines came thousands of workers and their families, most of them Mexican Americans and Latinos. For nearly a century, they drilled and transported ore through tunnels for two dollars a day—half of what their Anglo counterparts earned. But in 1925, and again in the 1950s, the combination of collapsing metal prices and exhausted mineral veins sent the mining companies looking elsewhere, leaving tons of untreated mineral waste behind and no future for the workers who’d powered the industry. Now, more than half a century later, mining is coming back to Harshaw: South32, an Australia-based polymetallic mining company, estimates that there are still at least 155 million tons of high-grade metals hidden deep underground. It is currently doing exploratory drilling half a mile away from the ghost town, acquiring permits and gearing up to operate in the near future. But whether modern mining—with its much greater profits and the promise of better environmental safeguards—will leave a better legacy this time around remains to be seen.

Frank, Henry, Mike, and Juan Soto grew up in Harshaw in the 1940s and ’50s with their parents and three sisters. On a recent spring day, they sit around their family dining table on the south side of Tucson, 70 miles north of Harshaw. Angelita Soto, the fourth of the siblings, joins in by phone as the conversation flies back and forth in English and Spanish. The siblings laugh and reminisce about their childhoods: the pranks they played on each other, their backyard with its bounty of black walnuts, acorns, watercress, and fruit trees. The Soto kids grew up running around barefoot, without tap water or electricity. “We were poor, but we had everything,” says Angelita.

“Harshaw was named after the guy [who] founded the mines, but it already had a name: El Durazno,” says Henry Soto. “We still call it El Durazno [the peach].”

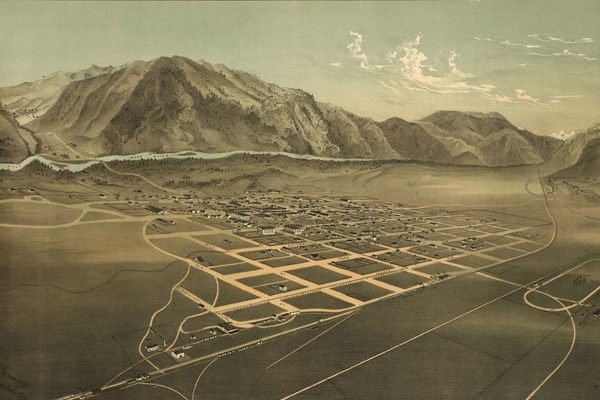

The Sotos have been in the West for nine generations, since before it became part of the United States. They came from Mexico in 1775, with the Spanish expeditions that founded San Francisco and Los Angeles. However, after the Mexican-American War ended in 1848, they suddenly found themselves foreigners in their own land, when the U.S. failed to honor the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and took their property rights away. The Sotos believe this is what pushed Angel and Josefa, their great-grandparents, to leave California in the 1870s. During the gold rush years, the couple headed eastward, jumping from mining camp to mining camp until they finally reached Harshaw—then a town bustling with 2,000 people, 30 saloons, several breweries and shops, a church, a school, and a post office. Only 8 miles away, in the town of Patagonia, the Pacific Railroad connected the local mines to the rest of the West.

“Harshaw at that time was booming, and word got around,” says Frank Soto, the oldest sibling.

According to the Soto brothers, Angel’s first job was probably at World’s Fair, the district’s deepest mine, extracting silver, gold, lead, and copper with chisel and bar through nearly two miles of underground shafts, 500 feet below the ground. Less than two decades later, Angel’s kids and grandkids would do the same work with air-pressure jackhammers, powder, and dynamite.

Most mining companies relocated when the Great Depression took its toll, leaving toxic waste rock that would leak acidic surface waters downstream for decades to come. The workers left town or survived by taking jobs in railroad and highway construction; the Soto family joined the Civilian Conservation Corps. The once-thriving town dwindled into a scatter of abandoned shacks. “There was nothing else, so people just packed up and left the houses,” says Mike Soto, the second of the siblings.

When the American Smelting and Refining Company (Asarco) took over in 1939, it resumed operations at the Trench and Flux mines, where Miguel, Mike’s father, pushed mineral-bearing ore wagons out of the shafts. Less than three decades later, however, Asarco halted operations and abandoned 2 million tons of untreated hazardous waste. The workers’ families moved away. The Sotos left Harshaw in 1956 and eventually relocated to Tucson’s south side, where Miguel Soto and three of his kids found work in the nearby Pima Mine.

With mining in retreat and no one staking deeds over the land, the U.S. Forest Service reclaimed Harshaw in the 1960s, knocking houses down as soon as the occupants moved out or passed away. Eventually, the entire town was bulldozed.

Today, half a mile from the Soto homestead, a third wave of mining is gaining speed. A dirt road passes the old Harshaw cemetery and climbs a four-lane drive to the hilltop where South32’s mining operation is located. Galvanized fencing and security cameras line the nearby roads.

South32, which purchased the Hermosa project in 2018, is currently doing exploratory drilling in what is probably the largest undeveloped zinc deposit in the world. The “Mine of Tomorrow,” as South32 calls it, would be largely underground, 2,000 to 4,000 feet. Most of the mining will be on private property, but some of the tunnels will extend horizontally into the deposits of zinc, lead and silver that exist underneath Coronado National Forest.

Not everyone welcomes the prospect of renewed mining: The Patagonia Area Resource Alliance (PARA), a local environmental organization, fears that South32 could deplete the region’s water supply and pollute the surrounding environment. “They go through aquifers when they drill to get their core samples,” says Glen Goodwin, a longtime local resident and PARA co-founder, explaining that the company would need to draw large volumes of water in order to reach the deposit. “They claim that there is no cross-contamination. How they can guarantee that, I don’t know.” A South 32 spokesperson has assured Patagonia residents that there will be little to no environmental impact.

While mining technology has evolved from what it was a century ago, environmental policy has lagged behind: The U.S. Government Accountability Office reports that, over a period of just 11 years, taxpayers had to pay $2.6 billion for the cleanup of abandoned mines. Only in 2001 did the Bureau of Land Management start requiring mine operators to prove they can pay for their own cleanup, though the GAO later acknowledged that the requirements were insufficient and the system used to track financial assurances was unreliable.

Through it all, the Sotos have continued to visit El Durazno almost every week. In fact, they never really left: In the 1930s, their grandfather, Tata Mariano, acquired 60 acres on the edge of Harshaw through the Homestead Act, thereby ensuring his family’s legal claims to the land. Some of his descendants still live there today. “I have a theory of why my grandfather had the vision to get a homestead when other Chicanos didn’t,” says Juan Soto, the self-described family historian. “It was the memory of dispossession.” He goes on to explain how the memory of the broken Guadalupe Treaty left Mariano Soto feeling wary, pushing him to get titles on land that others took for granted.

The Sotos keep a calendar to rotate visits to their homestead, where they spend the night, breathe the fresh air, and pick acorns and wild oregano in the nearby mountains. Yet they, too, have mixed feelings about the resumption of mining.

“We are a mining family, so to me a mine is just another mine,” says Henry Soto, who worked as a surveyor at Pima Mine for about 10 years. Still, he can’t help worrying that the new venture will entirely transform the place where he finds peace. “But it is too close to home,” he says, “kind of a ‘not in my backyard’ thing.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook