How We Know That This Dinosaur Had Bright, Audacious Plumage

Microscopic structures hint at an iridescent past.

Don’t be fooled by the fossil’s slate hue: Newly discovered Caihong juji, a winged dinosaur that roamed what is now China around 161 million years ago, was likely bursting with color—a shock of blue and green around its face, and streaks of orange highlighting its wings and tail. The duck-sized theropod has already been christened with the Mandarin word for “rainbow.”

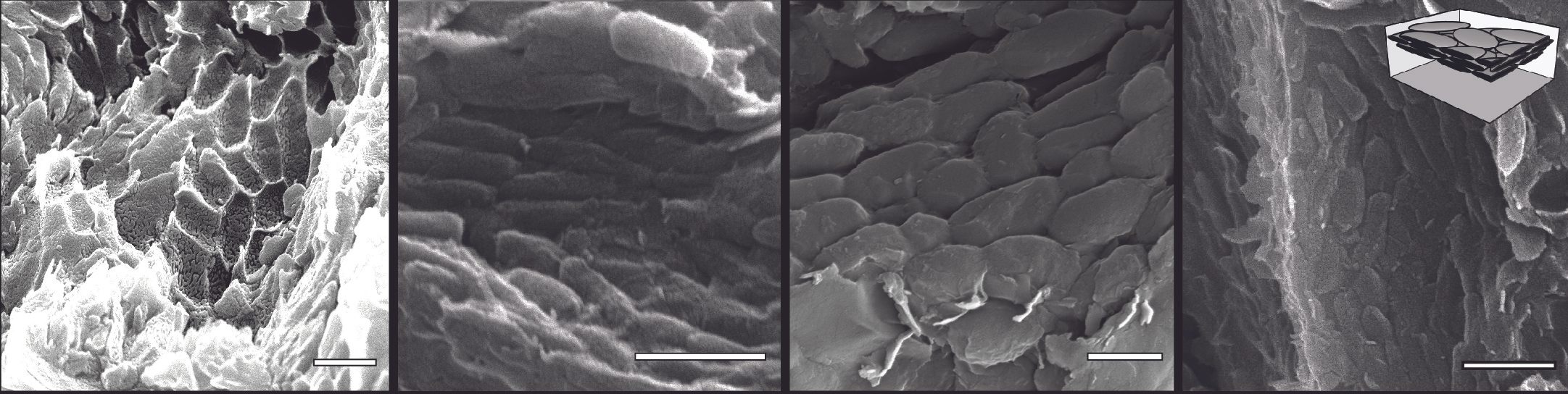

All those colors are long gone to the human eye, but because feathers owe their color to microscopic anatomy, striking evidence of the dinosaur’s plumage is still there to be found. By looking at the feathers of C. juji with a scanning electron microscope, a team led by China’s Shenyang Normal University was able to speculate about its once-dazzling coloration.

The feathers on this fossil stand out because they preserve the pigment-storing parts of cells, called melanosomes. If you smashed a feather to smithereens, “you’d only see black dust,” said Chad Eliason, a postdoctoral researcher at the Field Museum, in a statement describing the work, which is newly published in Nature Communications. “The pigment in the feathers is black, but the shapes of the melanosomes that produce the pigment are what make the colors.”

To determine the relationship between the melanosomes’ shapes and particular colors, the researchers consulted a database, begun by researchers now at the University of Ghent, that holds thousands of scanning electron micrographs of melanosomes from modern birds in collections around the world. The platelet-shaped melanosomes around C. juji’s head, chest, and tail base recall the vivid, iridescent colors of some hummingbirds and swifts—but also the more muted charcoals and blacks common in penguins. (C. juji is thought to be the earliest known example of this melanosome shape.) The dinosaur’s melanosomes were arranged differently than a penguin’s, so the researchers settled on screeching neon over somber black.

Julia Clarke, a coauthor and paleontologist at the University of Texas, says that the melanosome database could help solve a number of future scientific puzzles—especially if it continues to grow. “The measurement data is out there but it is a lot of work to package the rest,” Clarke says. “It would be cool if the community could add to this dataset and we’d have an even richer resource.” And many more prehistoric colors would likely come out into the light.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook