To Conceive a Girl in Ancient Greece, Eat a Salad and Tie Your Right Testicle

Doctors wrote recipes to cure patients’ ailments and determine the sex of their children.

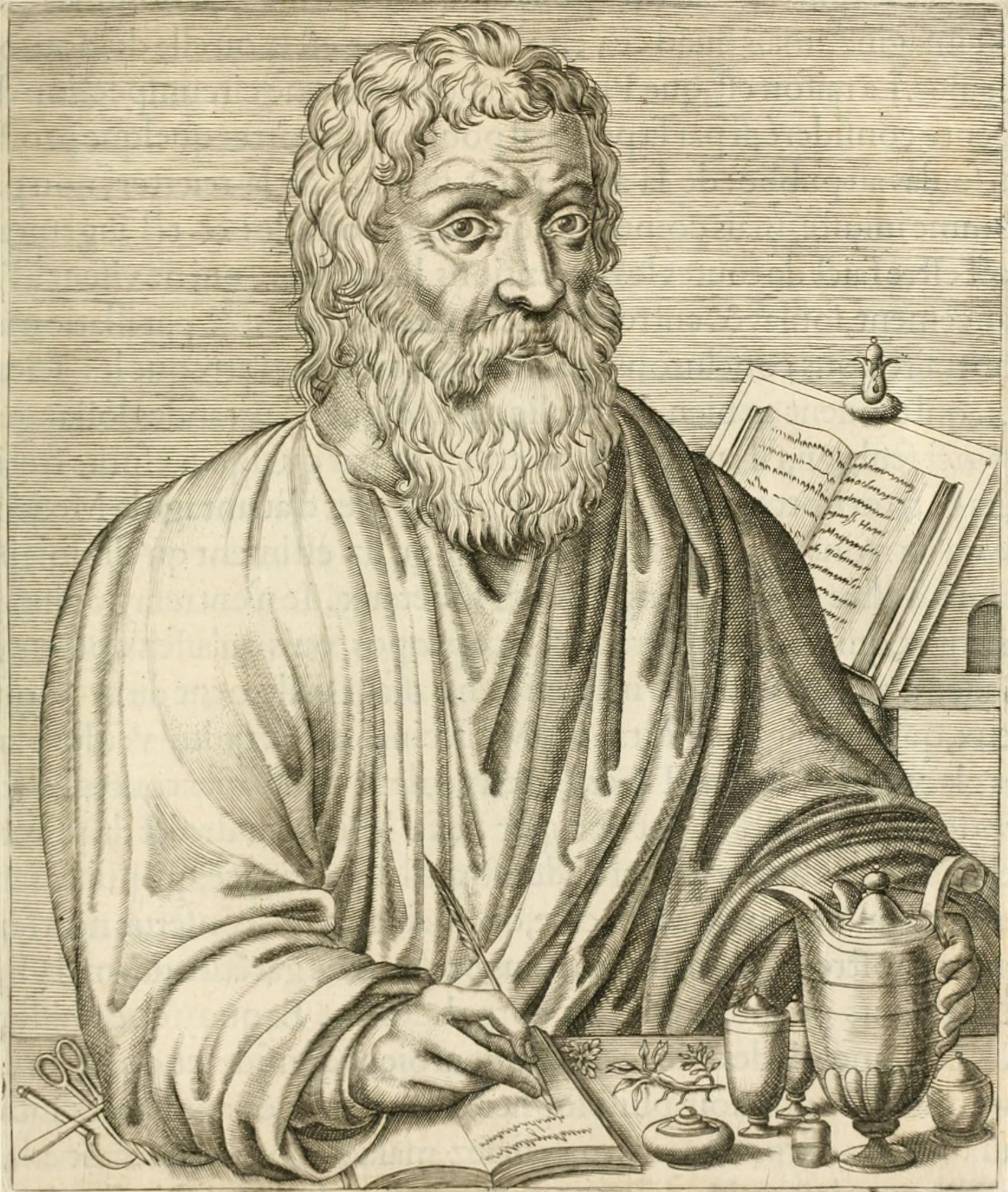

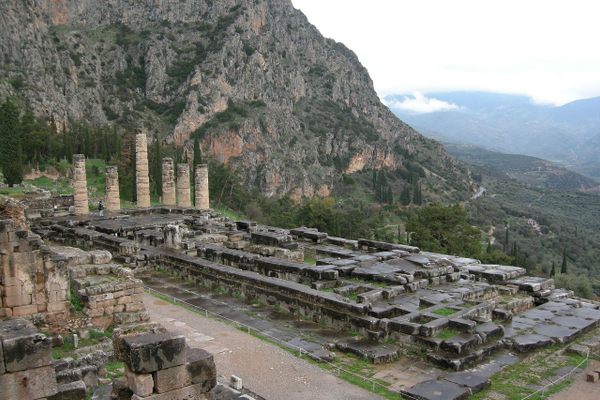

Greek women had it tough. At any moment, their wombs could dislodge and wander through their bodies, strangling them—or so said Hippocratic doctors. Their medical texts, which emerged in the fifth century B.C. and were attributed to the physician Hippocrates and his followers, changed Greek science by suggesting that illness had natural, rather than exclusively divine, causes. While wandering womb syndrome, which has been thoroughly discredited, is largely forgotten, one Hippocratic idea is likely familiar to modern parents: that what you eat can determine the sex of your child.

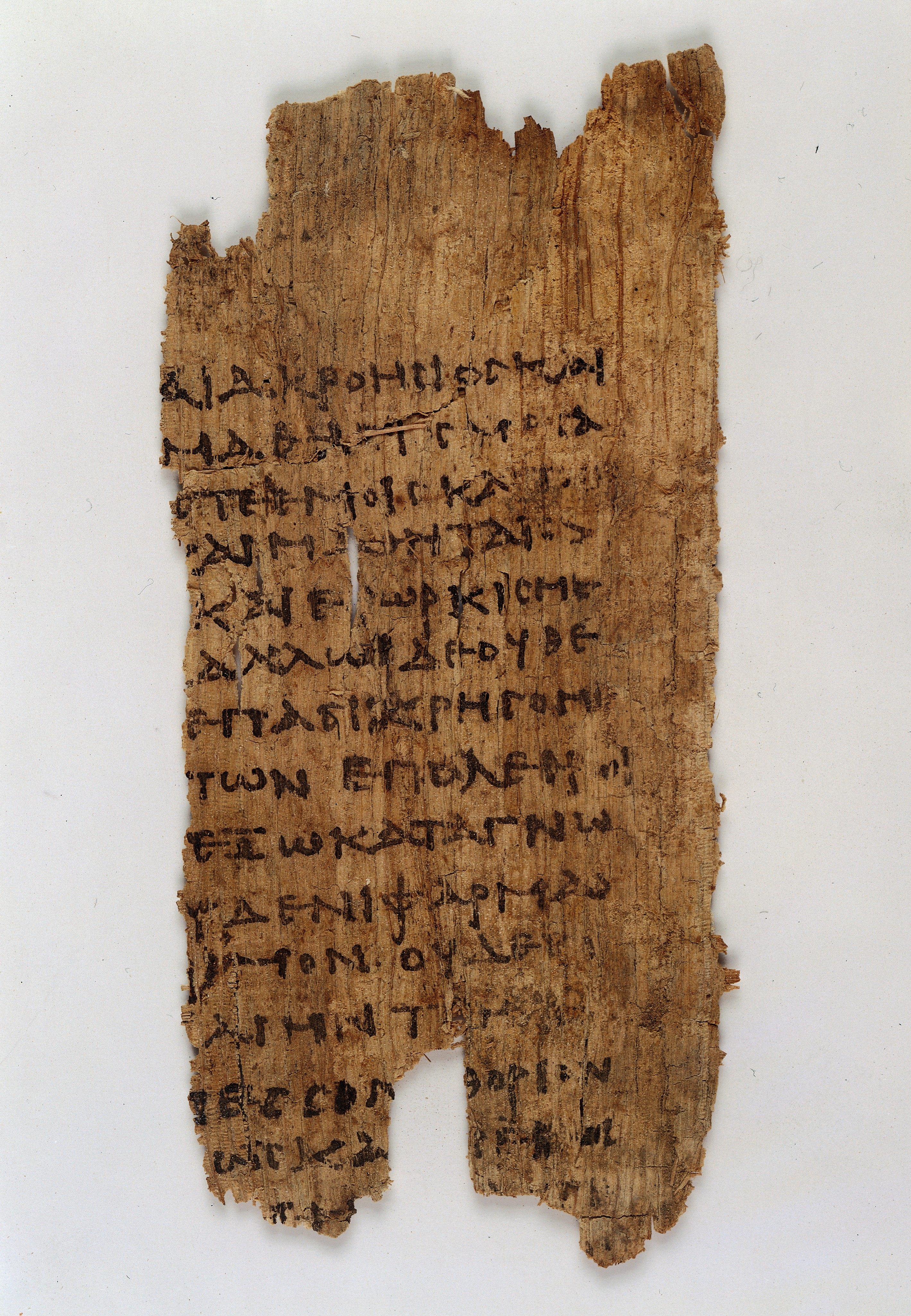

We don’t know much about Hippocrates’s life or contribution to the texts of the Hippocratic corpus, says Dr. Rebecca Fallas, a visiting research fellow in classical studies at the U.K.’s Open University who specializes in fertility in Ancient Greece. We do know, however, that Hippocratic texts were widely read in the centuries after they were written, and were compiled in the Great Library of Alexandria. Surviving texts show that Hippocratic doctors were, to put it lightly, very concerned with women’s reproductive health. In fact, the majority of the 1,500 existing Hippocratic recipes come from gynecological treatises. Of these, the dietary prescriptions for choosing the sex of one’s children reveal a complex set of beliefs around food, gender, and the human body.

Hippocratic doctors believed the body was ruled by four, or sometimes three, humors, classified according to heat and moisture. Phlegm was cold and wet. Blood was hot and wet. Yellow and black bile were dry and hot or cold, depending on the text. This system of heat and moisture underlied all aspects of patients’ health, including fertility.

Quick quiz: According to Hippocratic medicine, is coriander hot and dry, or cold and wet? What about lettuce? If you said coriander is hot and dry, and lettuce cold and wet, you’re right. But these classifications weren’t descriptions of foods’ literal moisture content and temperature. They were instead rooted in beliefs about how foods interact with bodily humors. Red wine, for example, was believed to heat and dry out the body, while white wine cooled and moistened it.

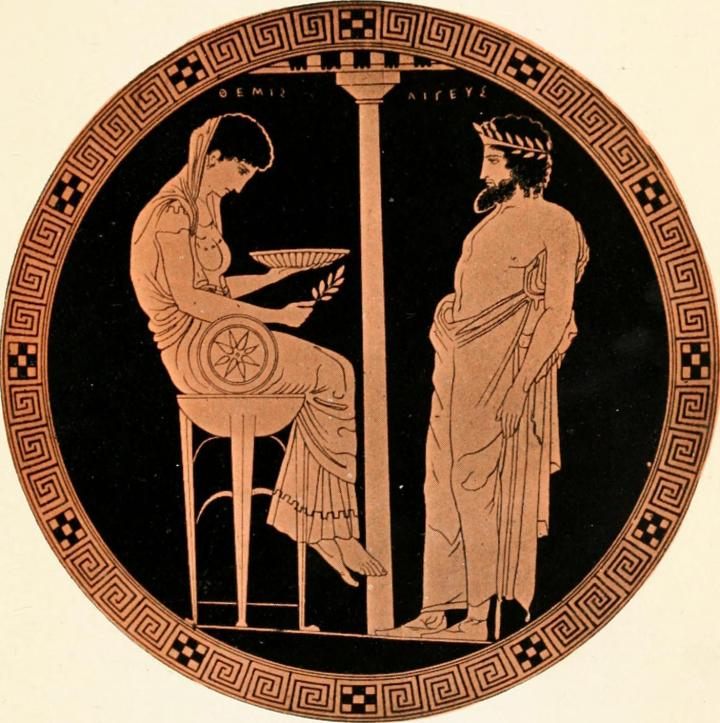

This delicate balance of humors was particularly important for women trying to conceive. With ancient couples facing high rates of infant mortality, producing healthy, viable children was a high-stakes affair. Boys and girls benefitted families in different ways: Boys promised future economic and political power, while girls offered the possibility of marriage alliances. While many scholars argue that Ancient Greeks valued boys over girls, there is evidence of women in holy shrines petitioning the gods for daughters.

As this system of medicine developed, Greek women had the option of skipping shrines and heading straight to a Hippocratic doctor. In the Hippocratic world, women were naturally weak, damp, and cold, while men were strong, dry, and hot. Doctors believed that conception resulted from a fight between “strong” male seed and “weak” female seed, with the winner determining the child’s sex. Hippocratic doctors advised parents hoping for boys to consume hot, dry, and strong foods, such as red wine sprinkled with black cumin. To conceive a girl, Hippocratic doctors prescribed wet, cool, feminine foods, such as lettuce and white wine.

But if couples were really serious about sex selection, diet alone wouldn’t cut it. Hippocratic doctors believed that the left side of the womb nourished female children, and the right nourished males. To choose a child’s sex, women had to conceive on the side of the womb corresponding to their preferred gender. So Hippocratic doctors advised couples who wanted girls to tie the male partner’s right testicle with string, thus hopefully directing sperm toward the left side of the womb. The opposite was true for conceiving a boy. Scholars have no evidence of this method delivering anything besides sore nether regions.

While modern-day dads have left the testicle-tying behind, some Hippocratic beliefs do persist. Thanks to first-century Roman physician Galen and the work of Arab and Renaissance translators, says Fallas, “Hippocratic and Galenic medicine became the cornerstone of Western European medicine.” This includes the Hippocratic oath, the ethical pledge that doctors do no harm. And just like their ancient counterparts, contemporary parents continue looking for dietary prescriptions, be they from scientific studies or friends, to determine their children’s sex.

While Fallas says scholars can’t know for sure if this contemporary dietary advice descends directly from Hippocratic medicine, some folk wisdom, such as the belief that eating veggies will help couples conceive girls, resembles ancient beliefs. Modern doctors say most of this advice is quack. But for Fallas, the enduring appeal of diet-based interventions stems not from their efficacy, but from women’s desire to control their own health, at home, with ingredients they have on hand. As for the methods’ effectiveness? “Well,” says Fallas, “You’ve got a 50/50 chance of getting it right.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook