Candid Portraits Smuggled From Behind the Iron Curtain

One American photographer’s inside look at the Soviet Union in the 1970s.

It was June 1977 when American photographer Nathan Farb first arrived in Novosibirsk, Siberia. He carried a 4-by-5-inch Polaroid camera, and an additional Polaroid 195, for his role in an upcoming Photography USA exhibition. It had been arranged by the United States Information Agency (USIA), whose remit was to promote American interests at height of the Cold War.

For Farb, this was a unique chance to see inside the Soviet Union—not Moscow, which was more than 2,000 miles away, or St. Petersberg. “Vice President Spiro Agnew and the conservative right talked about middle Americans,” he later recalled, “so I wanted to go to a ‘middle Russian’ city.”

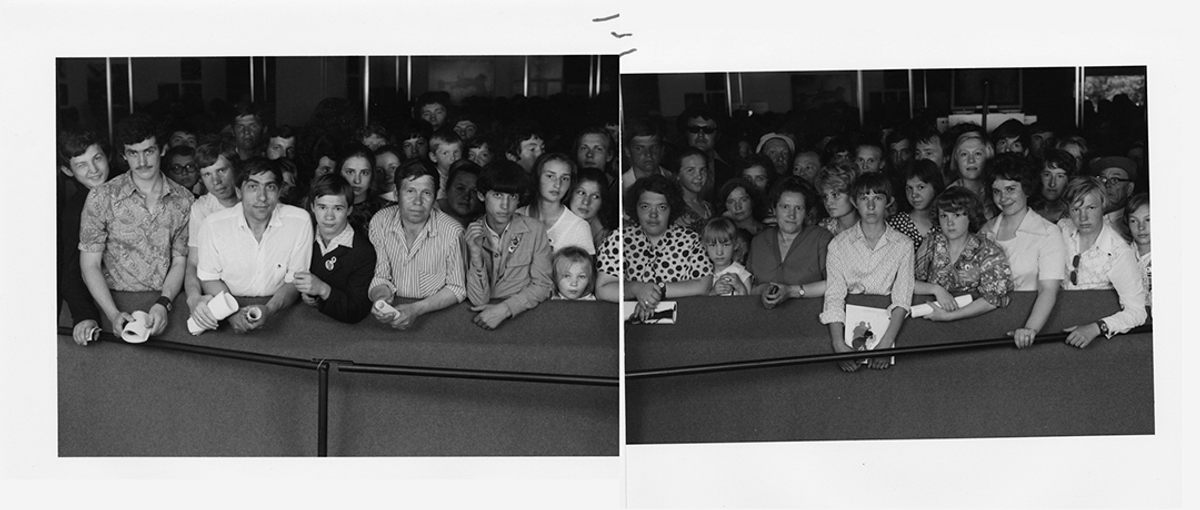

“I was supposed to be lecturing about photography,” he says, in a telephone interview with Atlas Obscura. Instead, over the course of six weeks, with his Polaroid cameras, in a temporary studio, Farb photographed the exhibition attendees. He took so many portraits that even Farb himself is unsure of the numbers: “Somewhere above 400 and maybe not more than 600 or 700.”

Farb offered his sitters a simple exchange. If they posed for portraits, they would receive prints of them. “It was really easy. There was no persuasion. Literally hundreds of people would line up.”

“This was an unusual film,” he notes. “It had both a positive and a negative.” Farb had used the same film on the streets of New York, when he had sold portraits to people that he would put on buttons. Doing this “explicitly for them, not as a journalist or as an artist,” he found, was more special, more “open, in a human way.” From this experience, he learned that offering his subjects physical prints would result in more candid responses. “I think that really helped the process a lot.”

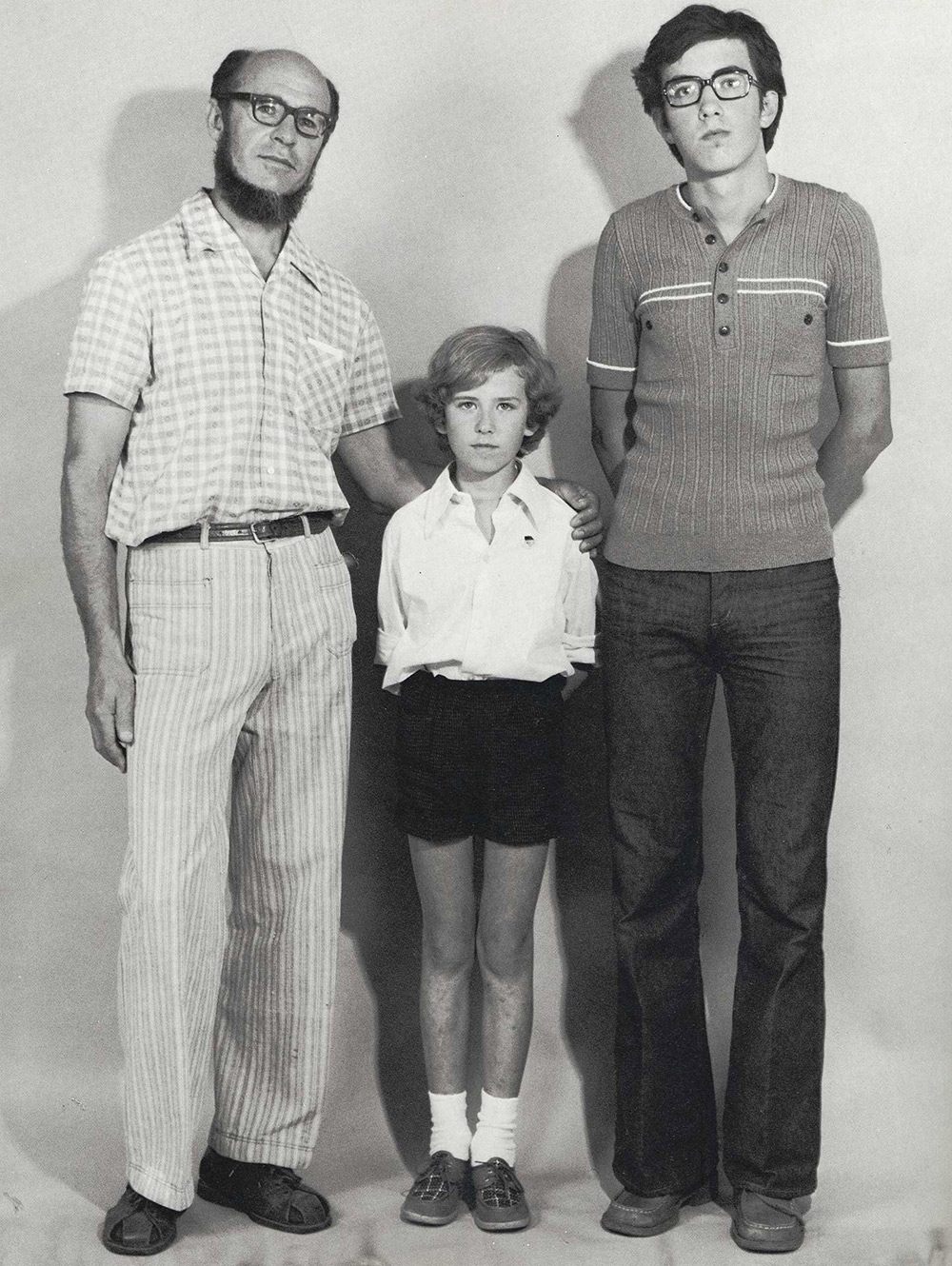

“I’ve always thought of a portrait as a collaboration anyway, so they were an active participant in it,” he says. His choice of subjects was also deliberate. “I was also trying to select a cross-section of people,” and had previously observed that Eastern Bloc weren’t as classless as they purported to be.

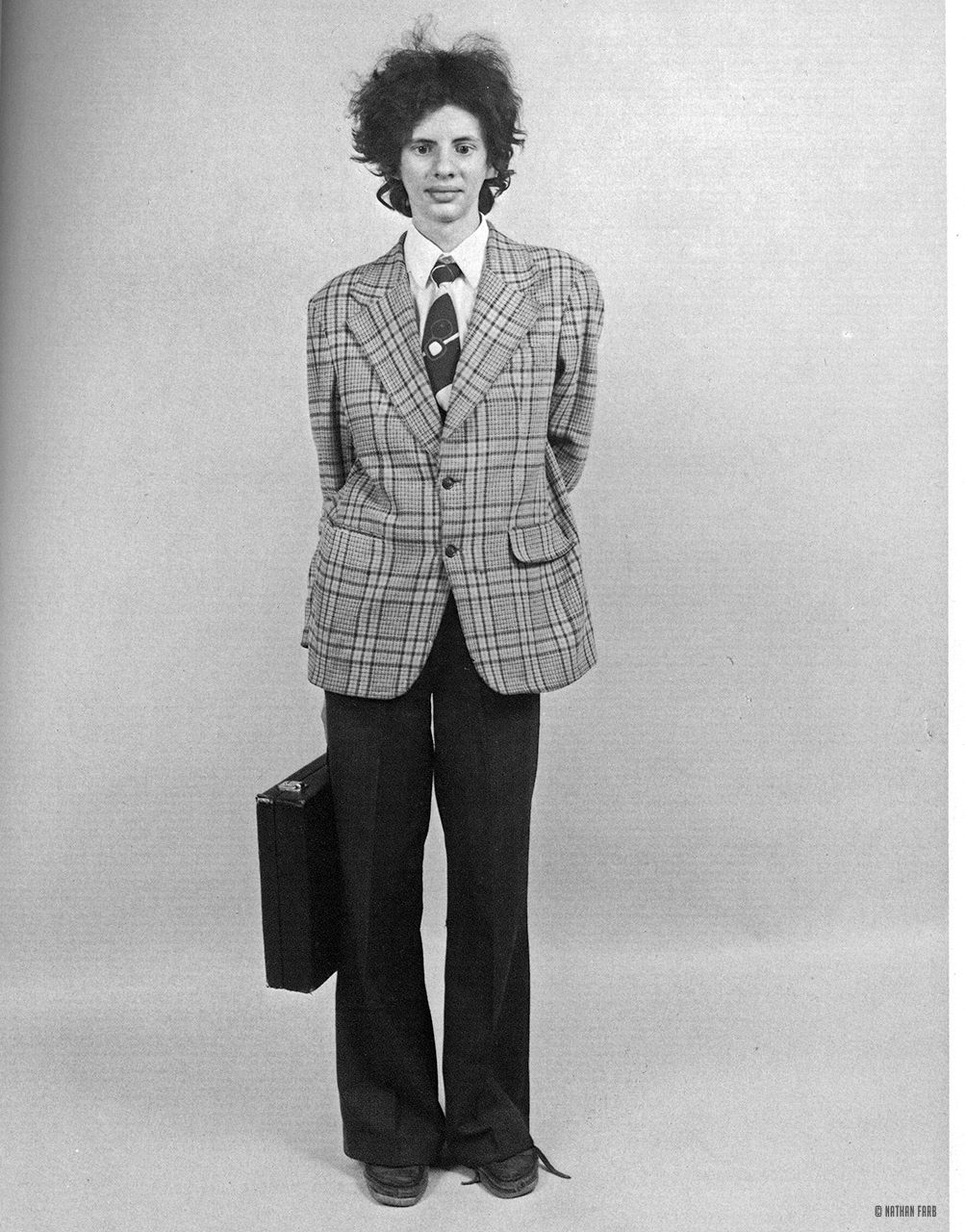

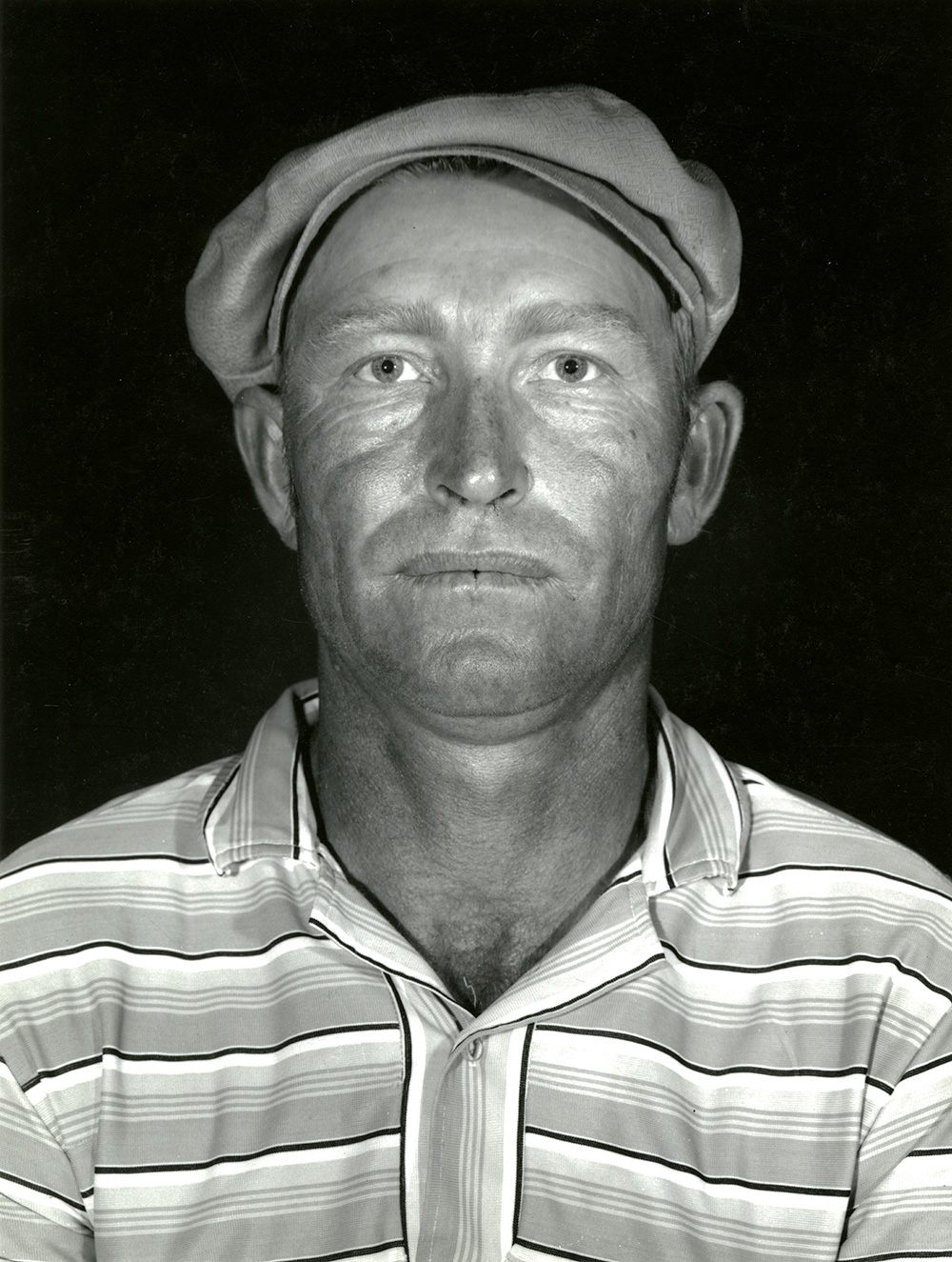

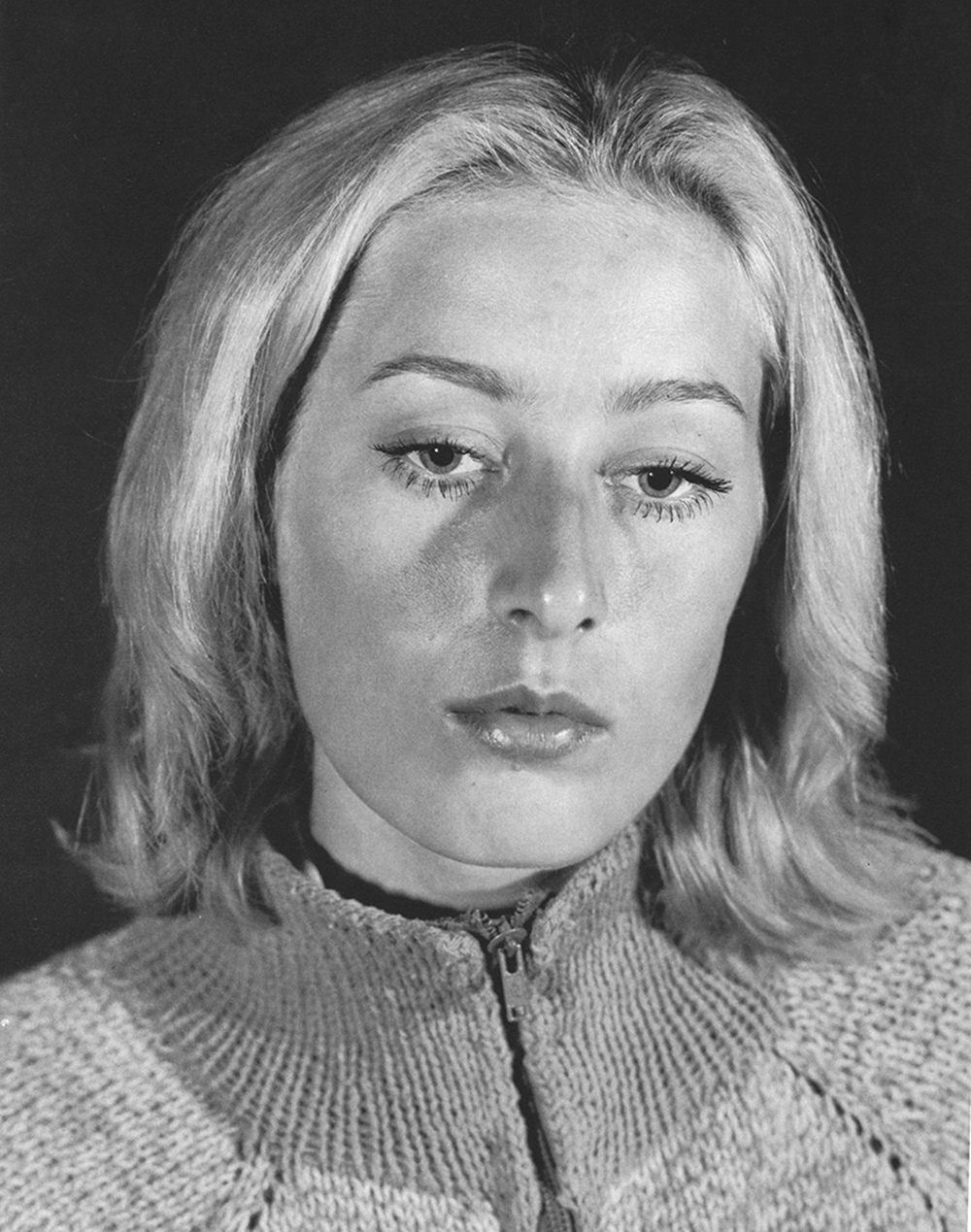

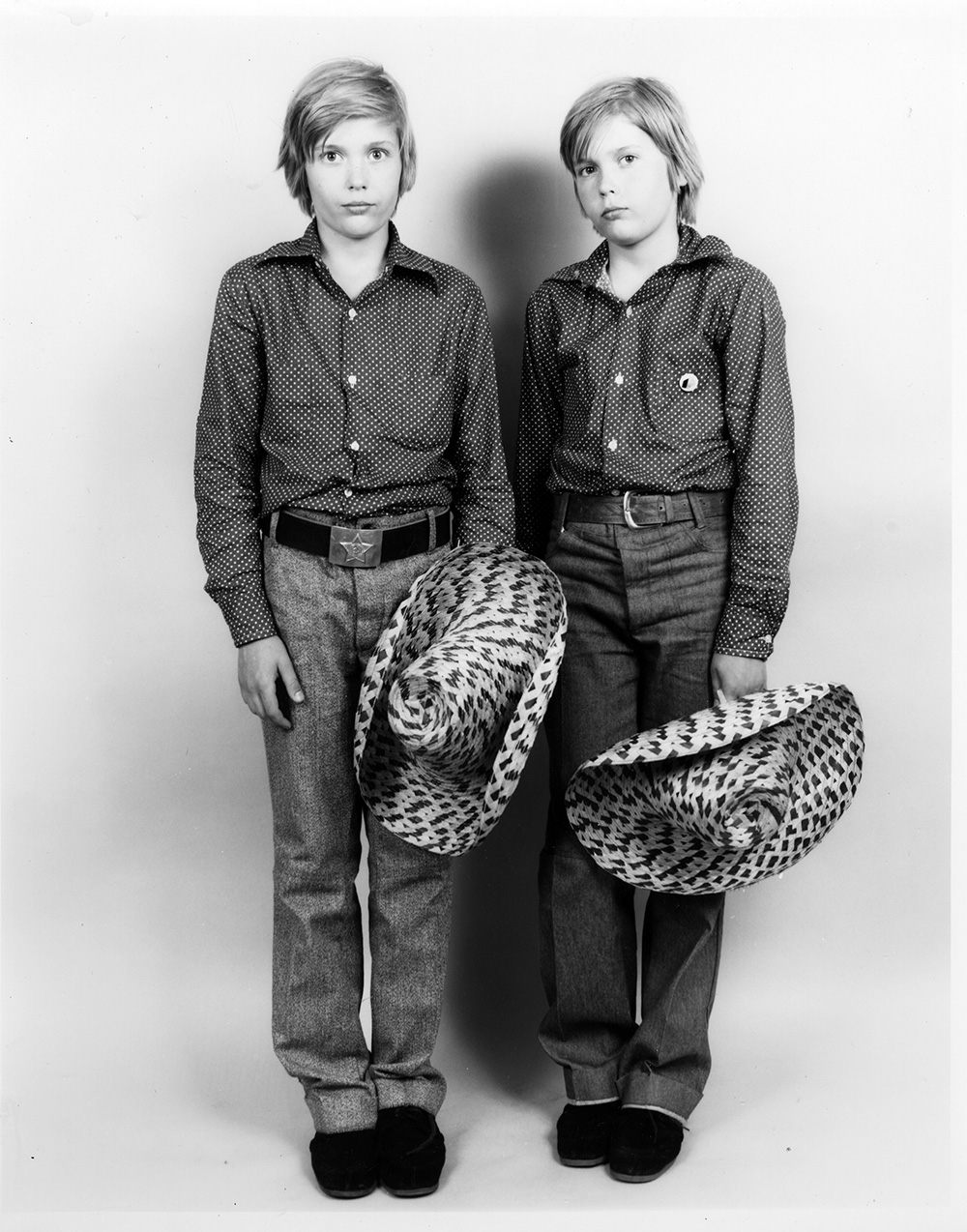

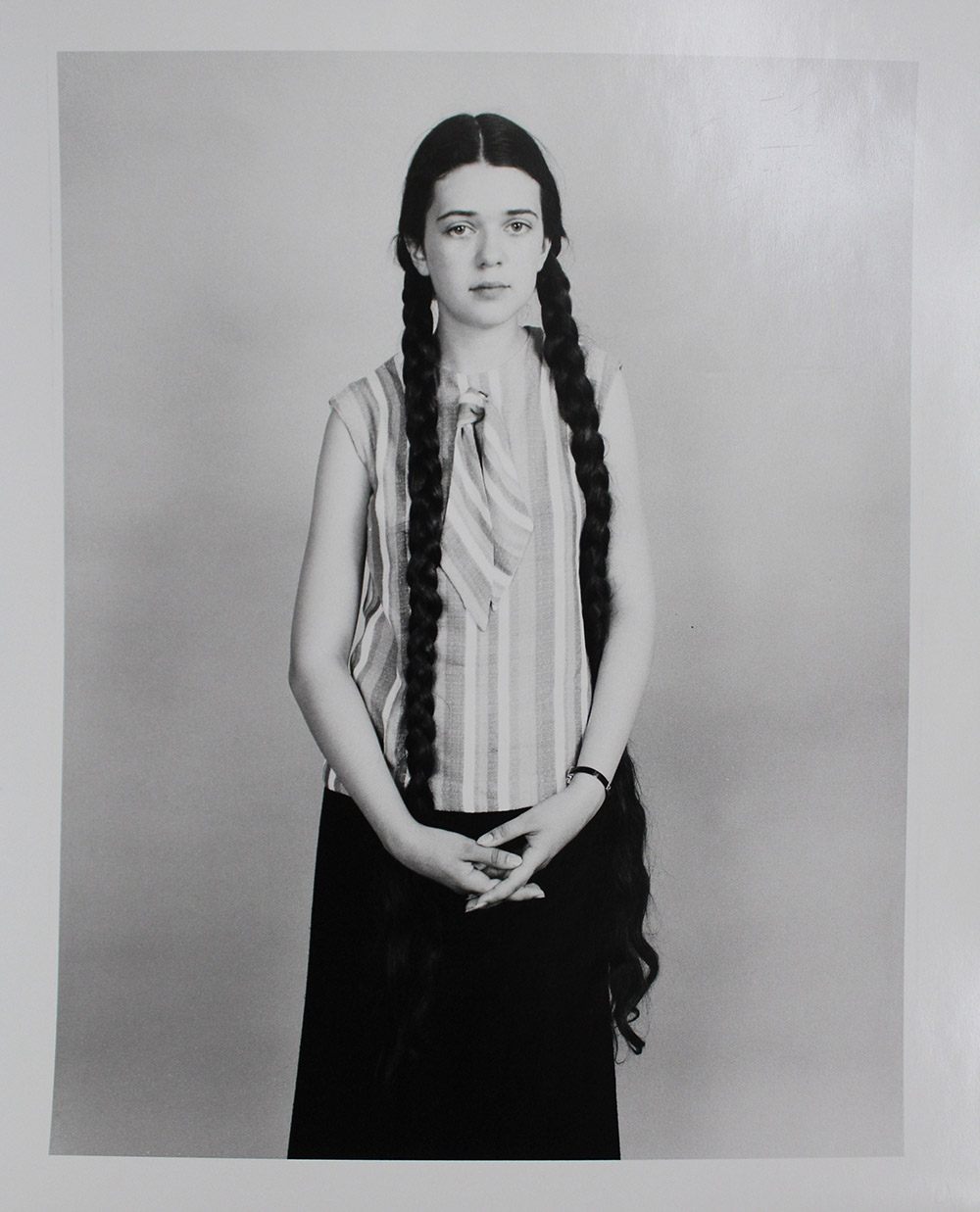

The resulting photographs are both unusually candid and departures from many of the preconceptions that Americans had about Soviet society in the 1970s. In one, a mother and daughter pose in complementary floral dresses. Another shows a boy standing stiffly in sunglasses and a trench coat. A third reveals a gangly student in classic 1970s style—flares, long hair—and holding a briefcase. This is Boris Klyachko, who reconnected with Farb in 2016, 39 years after his portrait was taken. In the intervening decades, the Soviet Union had crumbled, then collapsed, and Klyachko had immigrated to Australia in 1990. He remembered the exhibition as being “like a fairy tale .… That day’s Soviet brainwashing machine achieved completely opposite to the intention of the apparatchiks.” Of the portraits themselves, Klyachko stated, “As someone who lived in the USSR for 30 years I can attest that every single portrait … represents a slice of society that is immediately recognizable.”

As for Farb’s recollection of Kylachko, what he thought was most fascinating was that he “looked like he could have gone to my daughter’s school in New York.”

Unbeknownst to his subjects, Farb retained the negative of each photograph. He thought that they could be published once he was back in the United States. “I felt like I had this incredible opportunity to bring a document out of the Soviet Union of people that just had not been seen,” he says.

Farb began to smuggle the negatives out in batches, through the U.S. Embassy’s diplomatic pouches. Reflecting on it 40 years later, he doesn’t recall the circumstances that led to this decision, but he knew he had a lot of material that he wanted to share with the wider world. And while he’d been stopped several times while in the Soviet Union, he didn’t feel unduly concerned. “I didn’t think of it as smuggling,” he says. “I thought of it as getting them out safely.”

Or perhaps the smuggling was made easier by his belief that his portraits could serve a greater purpose. “I would make it possible that people would see exactly what these people were like, the suits they wore, what kind of clothing they had. I felt like I was—to say a little bit messianic is maybe a little bit of an understatement,” he says a little ruefully. “I couldn’t have worked as hard and did as much as I did in a short time if I hadn’t felt I was on some kind of mission.”

However, by the time Farb left Novosibirsk, the Soviet authorities seemed to be onto him. “When I left the country, when they were inspecting my bags, a supervisor came over to the guy inspecting my bag and he said, ‘His negatives have already left the country, you don’t have to look for them.’” Until that moment in his trip he had struggled to communicate in Russian, but “that was the first time I really felt confident I understood what somebody said!”

After his return to the United States, Farb did publish his portraits in a book, The Russians. His photographs will also soon be exhibited at the Wende Museum’s new space in Culver City. Atlas Obscura has a selection of Farb’s portraits. The exhibition runs from November 19, 2017, through April 29, 2018.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook