Found: Bottles of Hair Dye From a Civil War Photography Studio

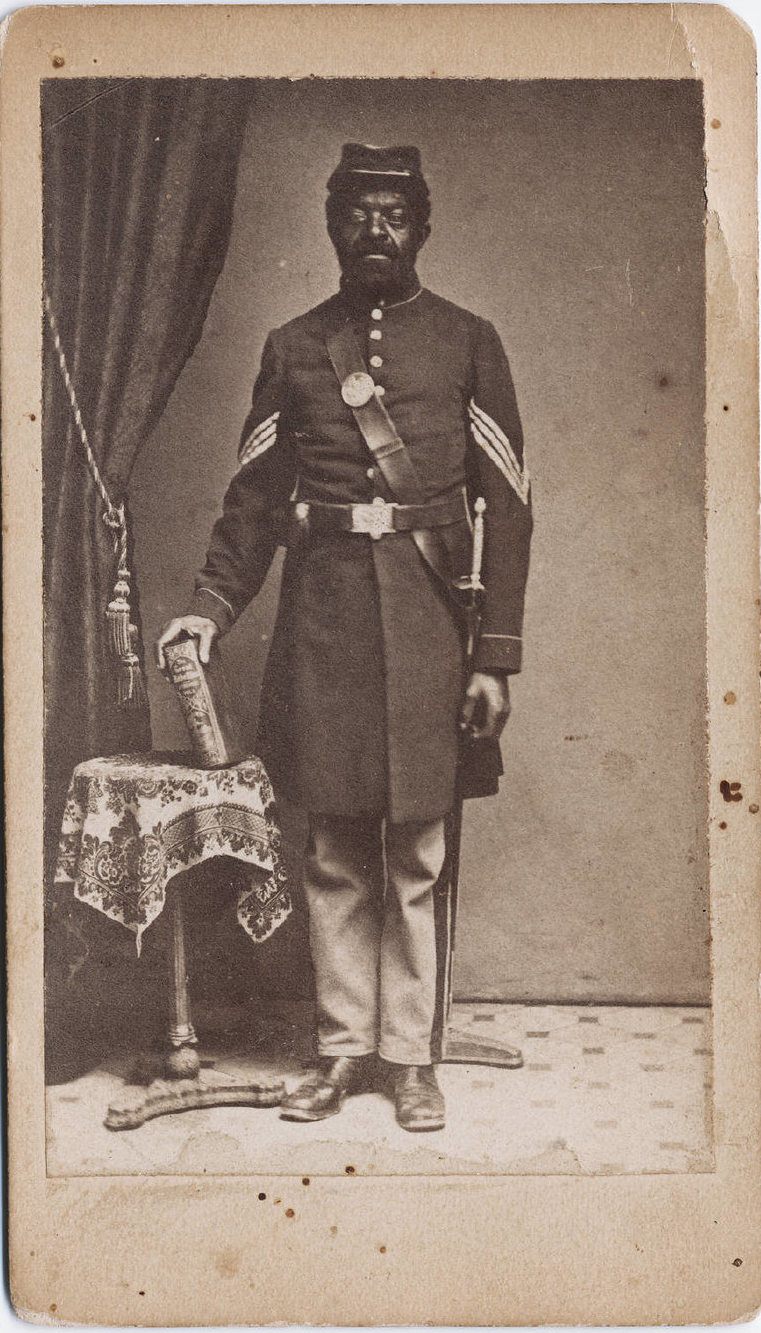

When soldiers posed for portraits, they wanted to look their best.

A few years ago, as archaeologists combed through the dirt of Camp Nelson, in Kentucky, they kept stumbling across bits of old glass. The several-thousand-acre landscape, which was designated as a National Monument in 2018, was a significant Civil War site, serving as a Union Army hospital and supply center, and one of the nation’s largest enlistment hubs for African Americans joining the U.S. Colored Troops. Before they headed to battle, many of the men likely posed for photographs—and, judging by the glass that has turned up on the site, scores of them seem to have dyed or shellacked their hair before they wandered in front of the camera.

Camp Nelson was a bustling place: Its grounds contained barracks and a hospital, plus kick-back spots including taverns and a billiards hall, the Lexington Herald-Ledger reported. Archaeologists have found smashed green and amber bottles—probably once full of since-glugged alcohol—and shards of other clear ones, which likely held ink for letters and reports. The more unusual bits of glass are the aqua of a cloudless sky. Hundreds of these fragments and clear ones clustered around the footprint of a former shop operated by a man named William Berkele, who managed a so-called sutler store—a civilian-run shop where enlisted men could stock up on candy, cigars, sardines, and other provisions that the military didn’t necessarily dole out.

The jagged pieces of clear and blue glass were jumbled together with other artifacts, like glass plates, bits of brass photograph mats, and a stencil reading “C.J. Young, Artist,” says Stephen McBride, director of interpretation at Camp Nelson. The presence of these other materials suggested to McBride and his fellow diggers that there was also a photography studio on the premises, perhaps operated by Cassius Jones Young, who was a photographer’s apprentice before the war, and later set up his own studio in Lexington, Kentucky. Once the archaeologists cleaned their finds and began to reassemble the the glass pieces back into the shape of bottles, they got a sense of the grooming products that they once contained.

The still-young medium of photography was tottering toward maturity just as the bloody war erupted. “The technology of photography was in rabid flux, and just as the war was about to begin, portrait photography had become much more accessible,” says Matt Gallman, a historian at the University of Florida and the author of several books about the Civil War. Because of the growing popularity of the carte de visite format—where eight exposures could be made on a single glass plate, then chopped apart and mounted onto slim calling cards—customers could pop into a portrait studio and wind up with several images to hand out. Photographers still struggled to capture movement as anything other than a blurry streak, and the labor-intensive, wet-plate photography technique was poorly suited to the front lines. As such, many Civil War photographs show young men either steeling themselves for conflict, or strewn across a battlefield, their bodies drained of life.

When they posed for photographs, soldiers often dressed up in crisp uniforms and brandished multiple weapons, some of them borrowed from the 19th-century portrait studio equivalent of a prop closet. They wanted to look strong, brave, and maybe even a little handsome. That’s where the grooming products came in.

It’s hard to gauge exactly how many 19th-century men were slathering their head with hair dye, says Sean Trainor, a lecturer at the University of Florida and historian who of men’s hairstyles. Men were “tremendously touchy” about the subject, he adds, because it was often seen as “foppish, vain, and unnatural.” But even if men didn’t fess up to purchasing hair dyes—which contained dangerous ingredients including silver nitrate, turpentine, and sulfur—Trainor says that it’s clear that they used them. Newspaper advertisements marketed these products, both through urban shops and via mail order, and men could even cook up chemical cocktails at home. “If I had to make a guess,” Trainor says, “I’d bet that middle-aged professionals and younger, fashionable men were the heaviest users of dyes—groups, incidentally, that were well-represented in the Union Army.”

McBride says that, according to a note he encountered in a book on Civil War photos, people sometimes darkened blonde, white, or salt-and-pepper hair for photos, so it didn’t look too washed out. “I’ve never seen any written evidence to confirm that dyeing one’s hair for photos was common,” Trainor says, “but it sounds reasonable.”

McBride and his collaborators used toothbrushes and warm water to scrub 150 years of dirt off the fragments. After that, the team began the finicky work of matching them with other bits from the same bottles. The lips and bases of bottles helped McBride’s team puzzle out the minimum number of containers they were working with. To piece them back together, the reconstructors applied a bit of superglue, added some masking tape to help fasten the pieces together, and then nestled the bottles into a bit of fine sand, to keep the repaired vessels stable while the glue dried.

Once McBride’s team had reassembled the bottles, they found that text marched down some of the sides. They embarked on a bit of detective work, scouring newspaper articles and books about historic bottles to learn about the companies that produced them and what they were advertised for. They found bottles of Dr. Jaynes (also spelled “Dr. Jayne’s”) and Cristadoro hair dye, plus Bear’s oil, which also claimed to make sparse locks a little bushier. Near the portrait studio site, the researchers found about 10 bottles of hair dye and seven bottles of hair oil. (None of those types of bottles showed up anywhere else at Camp Nelson.) Roughly half of them have been reconstructed. Though none are presently on view to the public, McBride hopes to exhibit some in the future.

Since the bottles were shattered and anything in them is long gone, McBride says it’s hard to say exactly what was inside. But Trainor suspects that the dyes would have been a beguiling dark brown or black. “As far as I know, virtually all available dyes darkened the hair,” he says. Even if blonde dyes had been available—and Trainor isn’t sure whether they were—they likely wouldn’t have been as popular as the inkier options. “Mid-nineteenth century Americans considered dark hair fetching,” he adds.

Soldiers knew that there was a good chance they wouldn’t return home from the war; at least 620,000 of them (and possibly many more) lost their lives. McBride’s team hasn’t yet found any of the photos that they believe were taken at the Camp Nelson studio, but the bottles are a reminder that, before they went to battle, many men tried to preserve their visage in portraits, and put their best face forward.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook