Victorian ‘Coffin Torpedoes’ Blasted Would-Be Body Snatchers

Grave robbing got more hazardous in the 1880s.

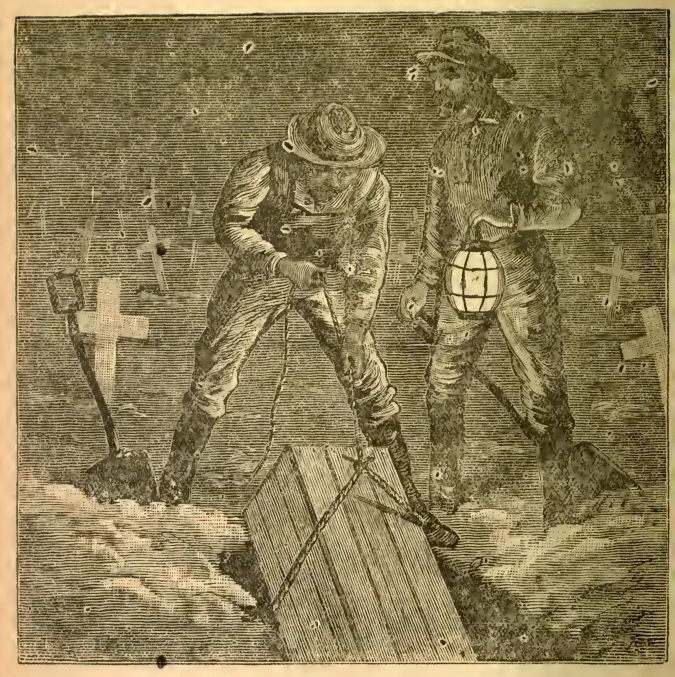

On the night of January 17, 1881, a would-be body snatcher by the name of Dipper was killed by a blast in a Mount Vernon, Ohio cemetery. The attempted grave-robbery was a three-man operation, according to the Stark County Democrat. The explosion broke the leg of the second thief. The third—tasked with keeping watch—was allegedly left unscathed and hoisted his wounded friend into a sleigh.

Another win for the coffin torpedo.

Keeping the dead buried was a matter of grave concern in 19th-century America. As medical schools proliferated after the Civil War, the field grew increasingly tied to the study of anatomy and practice of dissection. Professors needed bodies for young doctors to carve into and the pool of legally available corpses—executed criminals and body donors—was miniscule. Enter freelance body snatchers, dispatched to do the digging. By the late 1800s, the illicit body trade was flourishing, and salacious accounts of grave robberies peppered local papers across the country, historian Michael Sappol, Ph.D., chronicles in A Traffic of Dead Bodies.

At least 12 body-snatching scandals were reported in 1878, including that of Ohio congressman John Scott Harrison, the son of ninth United States president William Henry Harrison. (Harrison’s body was found at the University of Cincinnati and his remains were ultimately returned to the family tomb.)

Capitalizing on the public’s funereal anxiety, inventors got to work. Their solution? Explosives.

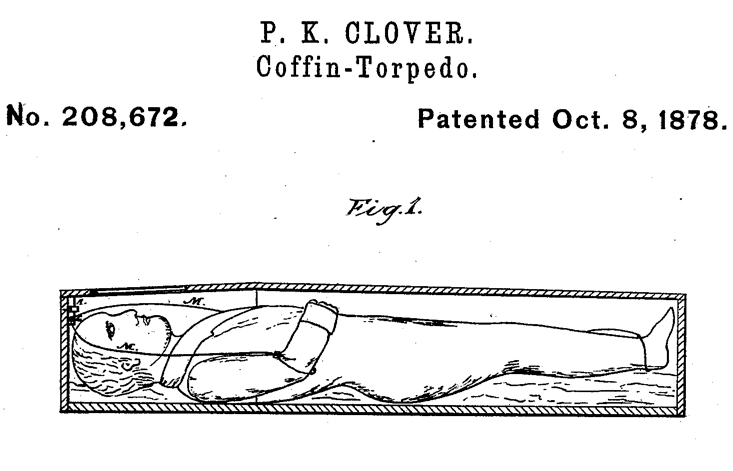

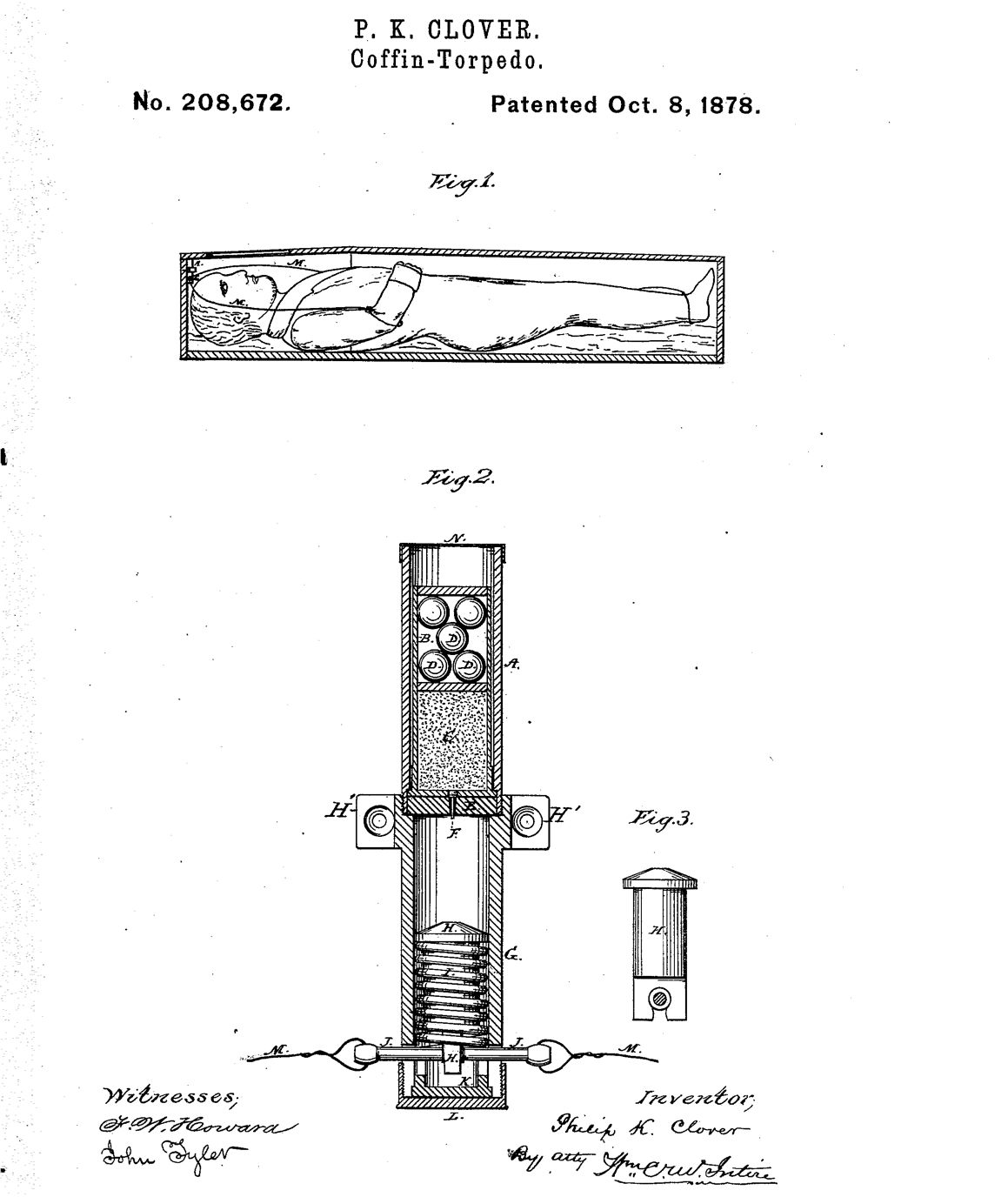

Philip. K Clover, a Columbus, Ohio artist, patented an early coffin torpedo in 1878. Clover’s instrument functioned like a small shotgun secured inside the coffin lid in order to “prevent the unauthorized resurrection of dead bodies,” as the inventor put it. If someone tried to remove a buried body, the torpedo would fire out a lethal blast of lead balls when the lid was pried open.

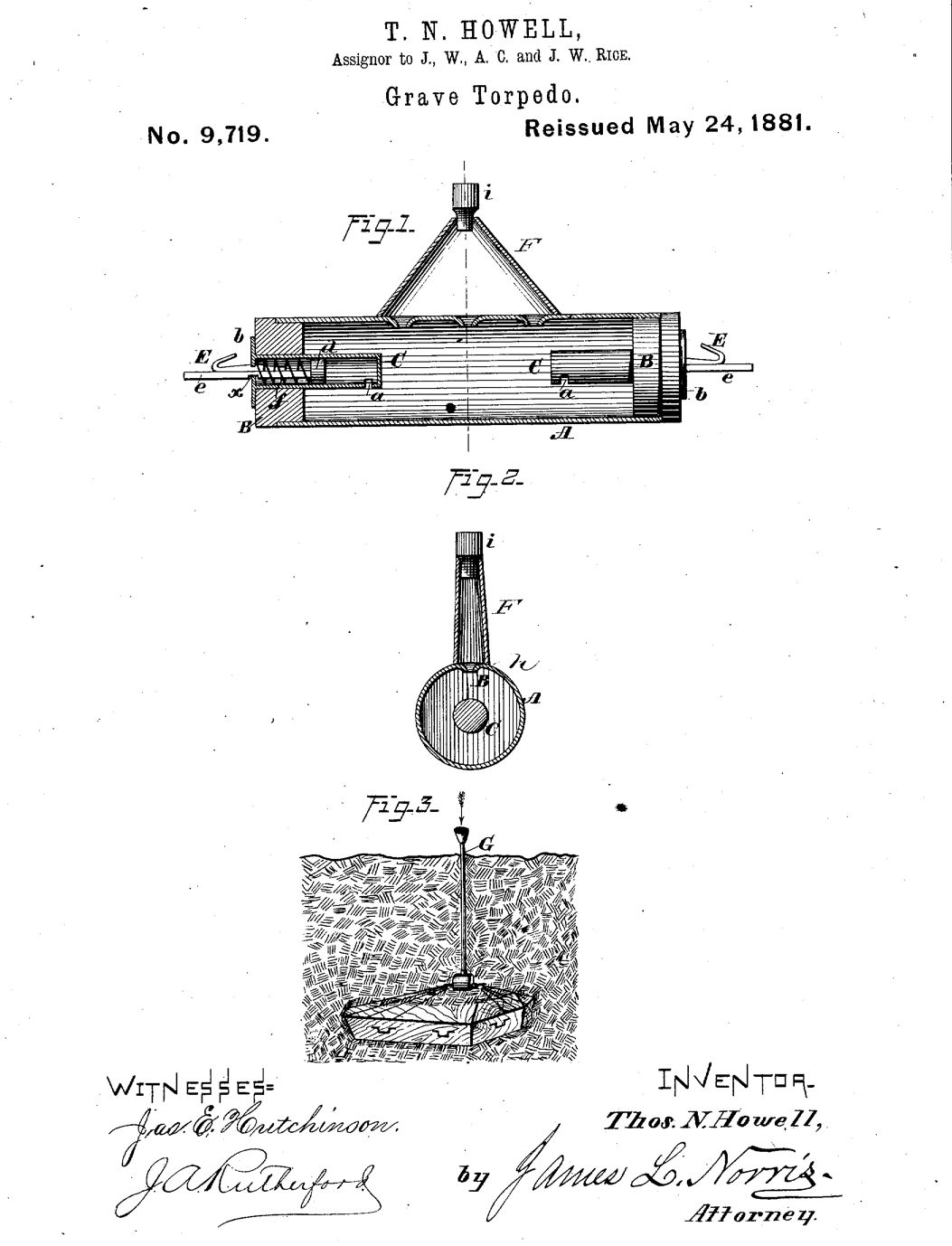

Another Ohioan, former Circleville probate judge Thomas N. Howell, patented a grave torpedo of his own on December 20, 1881. Unlike the Clover torpedo, Howell’s gadget was a shell buried above the coffin and wired to it. This worked like a landmine and would detonate when thieves ran into the wiring.

“Sleep well sweet angel, let no fears of ghouls disturb thy rest, for above thy shrouded form lies a torpedo, ready to make minced meat of anyone who attempts to convey you to the pickling vat,” read an advertisement for the Howell torpedo.

“It’s a period in which people devoted a considerable portion of their savings to funerals, and the development of a funeral industry around that,” Sappol says. “For many working people, if you saved any money at all, it might be for funeral expenses for you and your family. People felt that it was desperately important to have a ‘decent burial.’”

Lore of coffin torpedoes and graves loaded with them spread in patent catalogs and newsprint.

A particularly gossipy 1899 issue of the Topeka State Journal claimed the late Mrs. W.C. Whitney’s grave was “sown with powerful torpedoes” and fiercely guarded by watchmen at all hours. The report referenced the case of A.T. Stewart, a gilded-age tycoon whose body was taken from its grave in 1878 and held for ransom. “There is no secret about the torpedoes,” the Journal claimed. “All the village talks of them.”

Despite all the yellow rag chatter about graveyard artillery, there is little to suggest coffin torpedoes were widely manufactured or commercially successful.

“For the most part, these devices seem to have been used very little,” says anthropologist Dr. Kate Meyers Emery. “They were definitely oddities designed to make money off of the widespread fear about body snatching. The truth is, most of the time you really just needed someone to watch over your grave for a few days or weeks to make sure that the body had time to decay and wouldn’t be of use.”

Doctoral candidate Megan Springate, who authored the book Coffin Hardware in Nineteenth-century America is similarly unconvinced that coffin torpedoes made it out of patent catalogs. According to Springate, these news clippings probably reference “general explosives” placed around graves rather than inventions specific to the funeral industry.

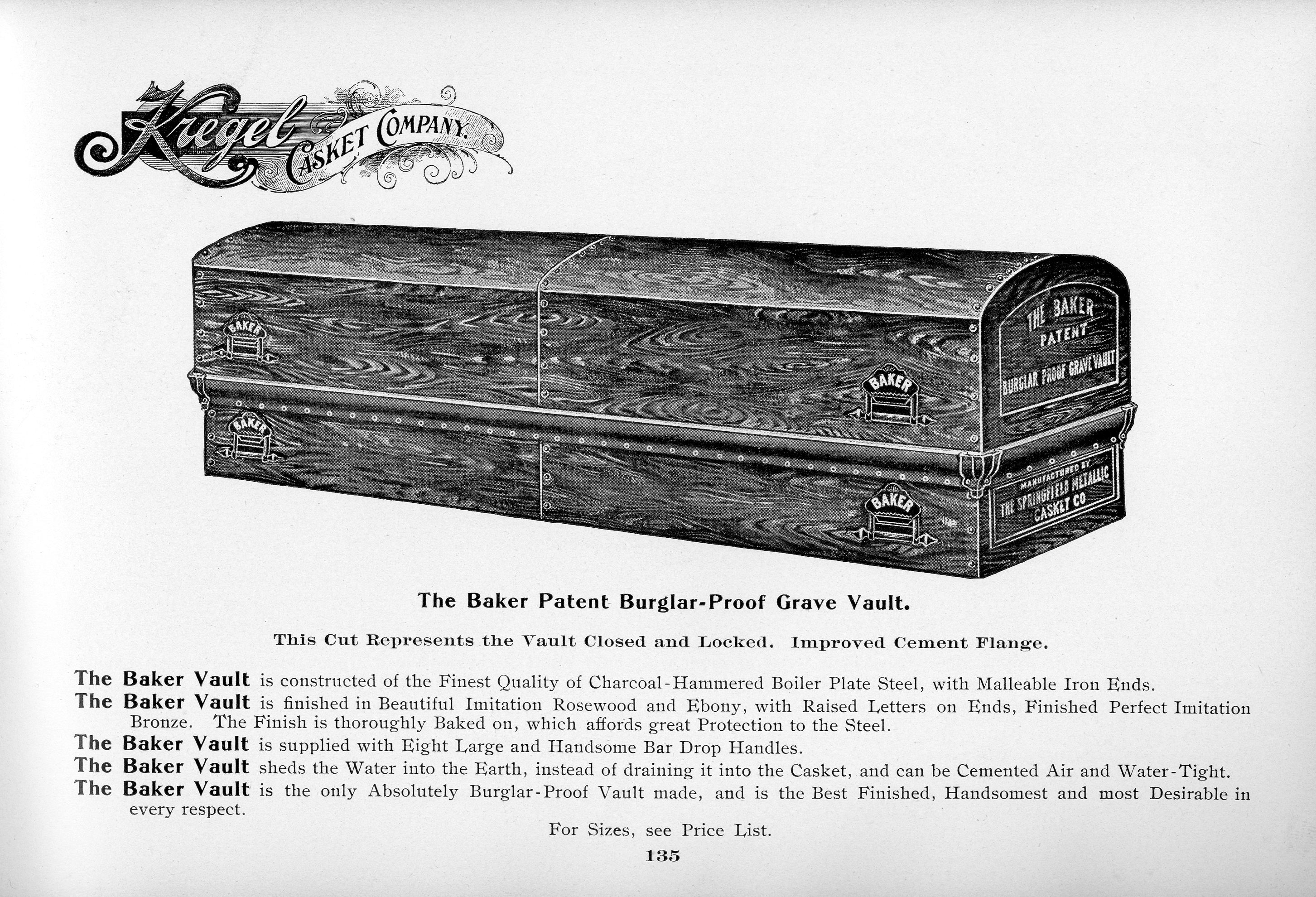

“Other aspects of the mortuary industry in the U.S. would have also deterred body snatching, including burial in sealed shipping crates as makeshift vaults, the use of hidden locking mechanisms on casket lids, and the use of cast iron coffins,” she says. “All of these have been recovered archaeologically.”

By the early 20th century, the controversy around resurrection men and the body trade had died down considerably—though not due to “grave ghouls” going out with a bang. Anatomy laws gave medical schools access to bodies of the poor in most states by 1913, curbing the black market for cadavers. Improved refrigeration technology also allowed corpses to be stored and preserved in medical institutions, so there was less of a premium on the newly deceased. Microbiology, advances in the surgical field, and early X-Rays relegated anatomical dissection to the sidelines of medical innovation. Anatomy continued to be taught in medical schools, but it primarily served as an introductory course, rather than the central focus of the medical curriculum.

Though there is little archaeological evidence of grave torpedo use, these inventions provide a peculiar window into the curiosity, horror, and unease anatomical practice inspired among 19th-century society.

“It’s a lost world, and part of it is the politics of death, the importance people attached to having a decent burial and the strong meanings they attached to narratives of death,” says Sappol. The industry that arose in service of that incorporated “casket and mausoleum manufacture, but also funerary clothes and trinkets, hearses, gravestones, post-mortem photography, and embalming post-Civil War.”

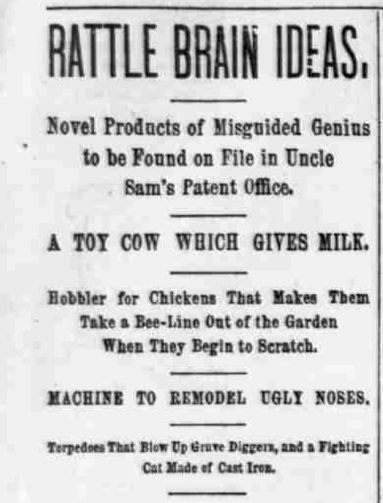

“Then there’s the tinkerers culture, people making goofy devices for perceived need or non-need,” Sappol says.

Addressing a coffin torpedo patent, Scientific American boasted: “In consequence of the increasing number of graveyard desecrations, the genius of the inventor has been incited to devise means of their defeat.” This clipping was reprinted in various local publications during the late 1870s and early 1880s.

Some accounts of coffin torpedoes and the tinkerers who thought them up take note of their impracticality. The Pittsburg Dispatch dedicated part of an 1890 round-up of “Rattle Brain Ideas” to cemetery explosives, locating them within the larger culture of invention and its esoteric, ill-conceived byproducts.

“There’s a premium on novelty and ingenuity,” Sappol says. “People in their barns have their tools, and they’re making stuff. Sometimes they make brilliant inventions and make fortunes, and sometimes they just make stupid things.”

Occasionally, they also made good punchlines.

The joke column of an 1882 Montana paper described the detonation of “one of the patent Ohio grave torpedoes.”. The device was being tested on a mule. At the point of explosion, the animal picked up a single hoof and continued grazing.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook