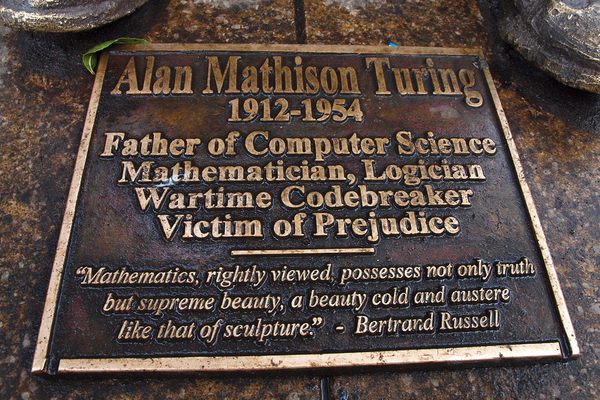

Listen to the First Computer-Generated Christmas Carols, From Alan Turing’s Lab

“Jingle Bells” and “Good King Wenceslas” haven’t sounded like this in a long time.

You only need five notes to play “Jingle Bells.” But even that would have been a challenge for the colossal early computers at Alan Turing’s pioneering Computing Machine Laboratory in Manchester, England. Though they were never designed to play music, the Ferranti Mark I and its successor, the Mark II, were able to generate some of the first computer-generated melodies in the world in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Now researchers from the Turing Archive at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand have used old recordings to recreate a now-lost 1951 BBC broadcast of a couple of Christmas carols.

As far back as 1948, researchers at the lab used the Mark I’s audible “hoot”—a short burst of sound for signaling users—to produce different notes. Turing wasn’t interested in making music, but a young schoolteacher, Christopher Strachey, had impressed him enough to gain access to the Mark II, and coaxed from it three melodies—“God Save the King,” “Baa Baa Black Sheep,” and Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood”—that were later recorded and broadcast on the radio. Jack Copeland, director of the Turing Archive, and composer Jason Long recently analyzed and restored a recording of that BBC performance, thought to be the earliest surviving recording of computer-generated music.

In old documents, Copeland and Long read that the BBC’s 1951 Christmas broadcast included computer renditions of “Jingle Bells” and “Good King Wenceslas,” but there are no known surviving recordings. The researchers saw an opportunity to use notes from the extant recordings to recreate what listeners heard 66 years ago. They cut and pasted, manufactured missing notes from what they know the computer was capable of, and stretched others out.

The result is a faithful rendition of what the Mark I or II would have sounded like when in a festive mood, but it’s not exactly easy on the ears. The timbre is somewhere between a foghorn and a sore violin, and there are some po-faced bum notes. “Because the computer chugged along at a sedate 4 kilohertz or so, hitting the right frequency was not always possible,” Copeland and Long wrote in a blog post for the British Library. “It’s a charming feature of this early music—even if it does in places make your ears cringe.”

Whether these versions will become holiday standards remains to be seen, but they do evoke some of the sense of wonder and bafflement radio listeners might have felt back in 1951.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook