Does Mrs. Claus Have a Life of Her Own?

Who are you, lady on the right? (Photo:

Here’s a trivia question for the festive season: What is the first name of Santa Claus’ wife?

Trick question. Not only does Mrs. Claus have no definitive first name, her identity is so tied up in that of her husband that she is best known for elf-wrangling, cookie baking, and assisting with toy assembly. Since she first emerged in the mid-19th century, Mrs. Claus has been a secondary character living in the shadow of her famous, workaholic husband. But along the way there have been glimmers of who she is as an independent person–and even a few suggestions for what her name could be.

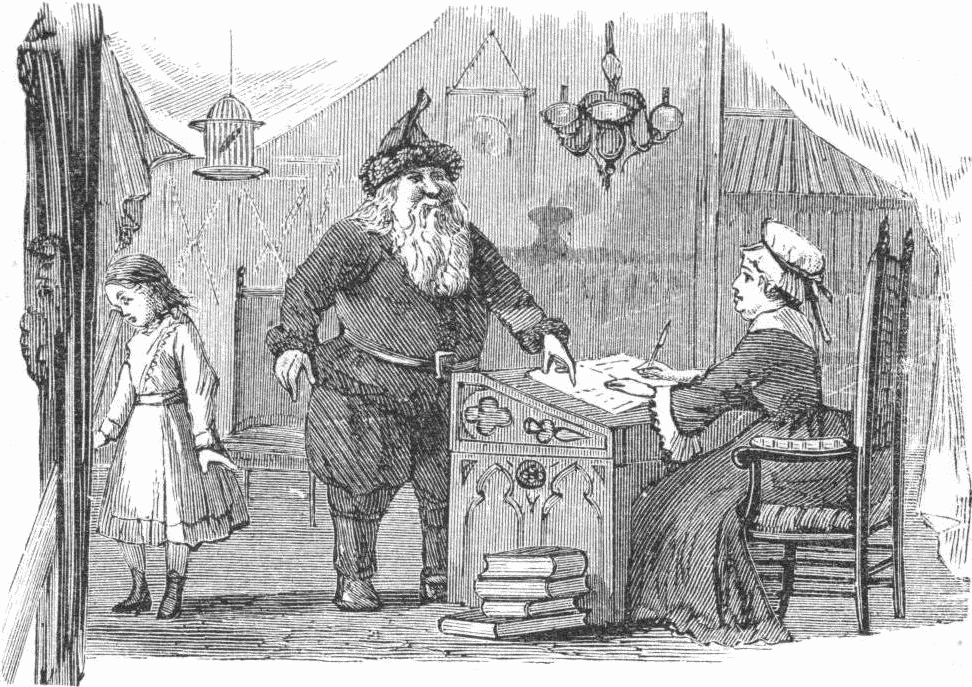

One of the first hints of Mrs Claus’ existence came in the 1878 children’s book Lill’s Travels in Santa Claus Land and Other Stories. In it, Lill, a young girl, goes for a stroll beyond the family orchard, encounters a wall that extends into the sky, and follows it to Santa Claus Land, where she encounters “a lady sitting by a golden desk, writing in a large book.”

This unnamed woman, whom Lill’s sister, Effie, speculates is “Mrs. Santa Claus,” is essentially Santa’s secretary. Lill watches as the big man in red spies on children through a telescope, then dictates his naughty-or-nice observations for the apparent Mrs. Claus to transcribe. An accompanying illustration shows the scene:

(Image: Wikipedia)

After lurking in the background of Santa-focused tales for a few decades, Mrs. Claus finally got a starring role in “Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride,” an 1889 poem by Katherine Lee Bates. The poem is told from the perspective of Mrs. Claus herself, who is given a name of sorts: Goody, which is short for Goodwife, a polite form of address once used in place of “Mrs.”

Goody has a few bones to pick with her jolly old husband. Bates depicts her as a dutiful wife prone to asking the odd passive-aggressive question. “Santa, wouldn’t it be pleasant to surprise me with a present?” she asks, having laid out the fact that Santa gets “all the glory of the joyous Christmas story” while “poor little Goody Santa Claus” gets “nothing but the work.” Two stanzas later, the resentment gets more intense:

You just sit here and grow chubby off the goodies in my cubby

From December to December, till your white beard sweeps your knees;

For you must allow, my Goodman, that you’re but a lazy woodman

And rely on me to foster all our fruitful Christmas trees.

Eventually, Goody convinces Santa to let her come on his Christmas Eve present delivery run, during which she fulfills her dream of descending a chimney to mend the hole-filled socks of a poverty-stricken child. Live it up, Goody.

In the 20th century, tales focusing on Mrs Claus tended to tell the same general story: Santa’s wife takes his sleigh on Christmas Eve, either sneakily while he is asleep, or by necessity due to him being incapacitated by illness or injury. She dresses in his clothes, stuffs her shirt with pillows, and makes the global round of deliveries, often screwing things up along the way by mixing up the presents—but in an endearing, forgivable manner.

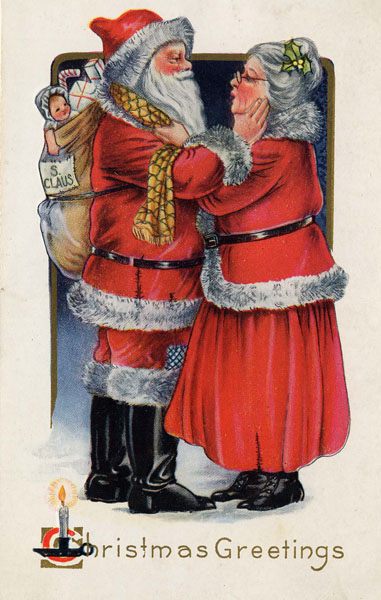

Despite appearances, Santa is not strangling his wife in this 1919 postcard. (Image: Wikipedia)

This “Mrs Claus delivers presents while Santa is indisposed” trope was established in a 1914 one-act comedic play entitled Mrs. Santa Claus, Militant. In this story, Mrs. Claus goes rogue and steals the sleigh while Santa sleeps, having gotten fed up with receiving no recognition for her hard work:

Here I sit year after year in Iceland dressing dolls and making candy bags and aprons and slippers and caps and what-not, and when they are all done Mr. Santa Claus just packs them in his sleigh and hitches his deer and away he goes to have all the fun and all the thanks. (Laughs merrily.)

Having discovered her ruse and chased her down, Santa resolves to take Mrs Claus—whom he refers to as “my helpmate”—along for the ride on all future Christmas deliveries. A similar storyline unfolds in the 1923 book The Great Adventure of Mrs. Santa Claus, as well as the 1963 poem, “How Mrs. Santa Claus Saved Christmas,” in which the “cozy, rosy, grandmotherly” woman accidentally delivers “ribbons to tomboys” and toy dump trucks to doll-loving girls. In all of these works, Mrs. Claus remains unnamed.

The most radical image shift for Mrs. Claus came in the 1970 Rankin/Bass stop-motion Christmas special Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town. The program tells the story of Kris Kringle, a plucky redheaded guy voiced by Mickey Rooney who goes on to become Santa Claus. In the tale, Kringle travels to Sombertown, a grey-hued bummer of a place in which toys have been outlawed. There he meets a school teacher named Miss Jessica who will eventually become his Mrs. Claus. Santa’s main squeeze goes from being a kindly, put-upon grandmother type to a fetching young fashionista with a real first name and a sleek red Vidal Sassoon-style coif.

Miss Jessica; future Mrs. Claus. (Screenshot from Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town)

The Rankin/Bass depiction of Mrs. Claus as a hip chick with a beehive is something of an anomaly, but it did usher in stories of Mrs. Claus that give her a fuller life of her own. The 21st century has thus far shown a greater appreciation for Mrs. Claus as main character in books like A Bit of Applause for Mrs. Claus (2003), The Story of Mrs. Santa Claus (2007), and What Does Mrs. Claus Do? (2008).

As for her name, Mrs. Claus was called Anna in a 1996 made-for-TV film starring Angela Lansbury–though the title of the film was Mrs. Santa Claus. (The plot also follows the same old “Mrs. Claus, feeling neglected, takes the sleigh out for a joyride” story.) A 2011 children’s book about the origin story of Mrs. Claus dubbed her Annalina, while in Jeff Guinn’s 2006 book, The Autobiography of Santa Claus, Santa refers to his wife as Layla.

“She’s a much more interesting person than the meek little lady people usually picture,” he assures.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook