Florida Has More Archaeological Canoes Than Anywhere Else in the World

The oldest dugout ever found there is almost 7,000 years old.

Florida is the boating capital of the United States: In 2016, the state had more registered recreational boats than any other. But to Julie Duggins, an archaeologist for the state’s Division of Historical Resources, that nautical achievement is only the modern iteration of a history that goes back more than 6,000 years.

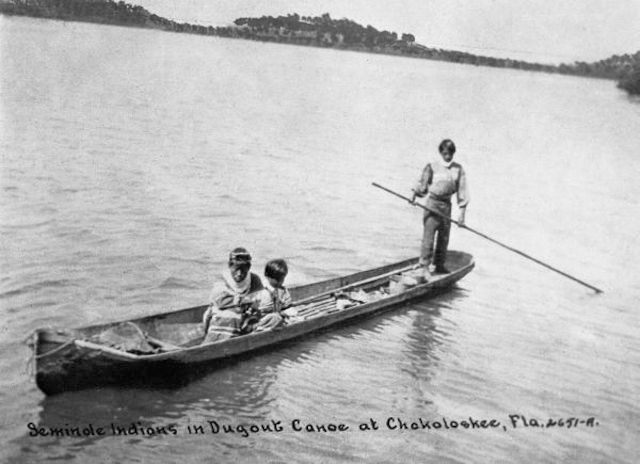

“Florida has always been a capital for watercraft and boating,” she says. More impressive than the state’s current boating record is its archaeological one. Florida has the highest concentration of archaeological dugout canoes of anywhere in the world—more than 400 wooden boats that show, as Duggins says, “how early Floridians navigated our rivers like highways.”

The most recent addition to that collection is a battered canoe spotted by a photographer out for a bike ride following Hurricane Irma in September. It has not yet been officially dated, but this newly discovered dugout—a canoe made from a single, hollowed-out log—has metal nails and other features that indicate it’s anywhere from a few decades to centuries old

For a Florida dugout, though, that’s not a particularly impressive age. Of the canoes in the state’s database, almost three-quarters are considered prehistoric, meaning that they were made before 1513, when Juan Ponce de Léon first documented his experiences on the peninsula. The earliest canoe ever found in the state is close to 7,000 years old.

Archaeologists there first started collecting information about these discoveries in the late 1970s, after a drought revealed a lot of long-preserved wooden artifacts. Barbara Purdy, who was an archaeologist at the University of Florida for many years, started surveying these ancient canoes and publishing ads that asked anyone who had found an ancient boat to call and report it.

There were heartbreaking moments in her quest. In 1985, a large company told Purdy its earthmovers had uncovered a trove of canoes and other artifacts. She and her colleagues took a sample of one boat and promised to return when the water table was lower, so they could excavate. That small sample indicated the canoe was 3,300 years old—the oldest they had discovered at the time. But when they came back the next year, the entire find had been destroyed.

By 1990, the state’s archaeologists had documented more than 200 canoes and found a much older example, dating back 5,120 years. One of the most intriguing aspects of these discoveries was that some canoes appeared in groups of up to nine boats, usually found on the shores of lakes. Purdy and her colleague Lee Ann Newsom wondered what might account for these concentrations. “There are accounts from other areas that Indians deliberately sunk their canoes if they were going to be gone for awhile in order to prevent their destruction from natural or enemy forces,” they wrote in 1990. Perhaps, they imagined, a group of people had used the canoes seasonally, sunk them for safekeeping, and never returned.

These dugout canoes turn up so often in Florida in part because the state is covered with expanses of peatland, wet and boggy soil where organic material decays slowly. Sunk in the muck, locked away from oxygen, wooden canoes can last for thousands of years with relatively little damage. Most often, they’re reemerge in times of drought, when the level of lakes and other waterways drops away.

The largest concentration of prehistoric dugout canoes found in Florida—most likely the largest cache of such boats anywhere in the world—appeared in 2000 on the shore of Newnans Lake, near Gainesville. That year, a severe drought had lowered the lake’s level, and hikers and bird watchers started spotting boats on the new shoreline. State archaeologists who documented the finds later wrote, “Every additional search revealed the remains of more canoes.” Sometimes, they’d be excavating a newly discovered canoe, and would reveal a few more in the process. In the end, they found 101 dugouts, the oldest dating back to 5,000 years ago.

When the locations of all the dugouts discovered in Florida are mapped, two concentrations stand out—Newnans Lake and another in the north central highlands. Duggins says this suggests that people were purposefully caching canoes in certain places. “It’s starting to look like perhaps those canoe sites represent points on the landscape that were strategically located between watersheds,” she says. She compares it to riding a bike to a subway station and locking it up there, so that on your return trip, the bike will be waiting for you. In other words, these canoe concentrations could represent nodes in an extensive transportation network that would have allowed people to travel efficiently over long distances.

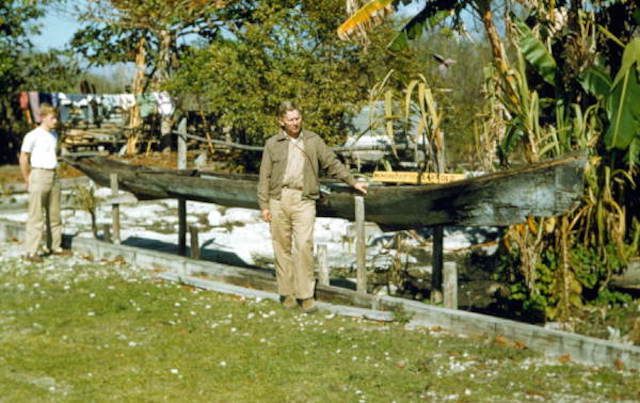

Part of the reason Duggins and her colleagues encourage the public to report dugouts when they find them is that the boats are incredibly delicate. Once exposed to light and air they can disintegrate rapidly, especially if moved. “Our rule of thumb is to leave it in place,” says Duggins. “If it’s been preserved for thousands of years in the bottom of the lake, the most protective thing is to leave it there.” The alternative is to place it in a bath of polyethylene glycol for a year or more, while the waxy substance replaces the structure of the wood. Every canoe, even ones that aren’t preserved like this, can be added to the state’s database and help fill out the picture of how people used these boats over thousands of years. “Even if it has been in someone’s barn for 50 years,” Duggins says, “we still want them to report it.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook