Enter Sandia Man: Revisiting the Site of a 20th Century Archeological Scandal

View from inside the Sandia Man Cave. (Photo: Skarz/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

In Las Huertas Canyon, northeast of Albuquerque, New Mexico, there is a cave that was once touted as holding astounding evidence of the earliest inhabitants on the North American continent.

It’s a strange place, positioned high up on the side of a sheer cliff wall, accessible by a winding metal staircase that leads to a three-sided cage over the cavern’s entrance. The cave itself is filled with red dust and the marks of old graffiti can be dimly seen on the stone walls. There is little to see inside: no impressive formations, no stunning “ballrooms” as in Carlsbad away to the south; only dust and the smell of ancient earth.

But this unassuming cave was once the setting of a strange, convoluted story —and, some would say, a scam that continues to create controversy in the halls of academia today.

In 1934, a graduate student named Frank Hibben, already a shining star of the archeology program at the nearby University of New Mexico, excavated the cave and discovered that it contained artifacts from as far back as the Folsom culture, then considered the earliest inhabitants of the Americas. But Hibben didn’t stop there. He kept digging, and soon found another cache of artifacts from what appeared to be a far older group of humans. He named the people of this group “Sandia Man,” and estimated that they had lived approximately 25,000 years ago, predating the Folsom culture by some 10,000 years. When the discovery was reported in a May, 1940 issue of Time magazine, Hibben, by then a full professor, was hailed as a revolutionary figure and the University of New Mexico became world renowned for its archeology and anthropology programs.

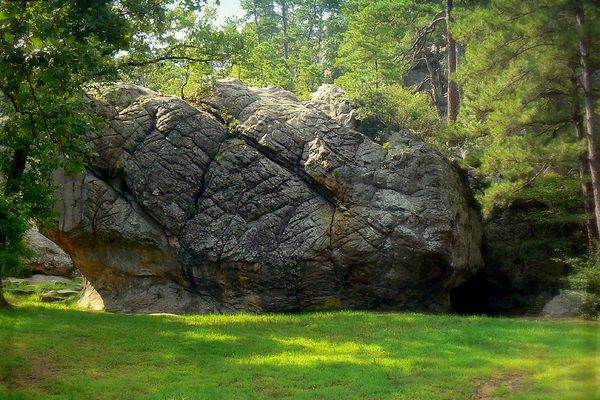

Set into the sheer side of Las Huertas Canyon, Sandia Cave offers a story of discovery and scandal. (Photo: Ty Bannerman)

But by the mid-1960s, other scholars began to levy disturbing allegations against Hibben and his discoveries at the cave. Decades of academic quibbling in various journals finally reached the public consciousness in 1995 when journalist and fiction author Douglas Preston published a damning article in the pages of the New Yorker. Archeologists who later visited the Sandia Cave site cast doubt on Hibben’s assertions that the artifacts were found beneath an unbroken crust. Researchers who had worked with samples purportedly from the site pointed to inconsistencies in the samples’ makeup, and, most disturbingly, suggested that the iconic “Sandia point,” a slope shouldered flint spear-head unique to Sandia Man and the European Solutrean complex, may have been planted in the cave by Hibben himself. The Sandia Man disappeared from textbooks.

Somehow, though, despite these allegations, Hibben’s personal reputation was strong enough to ensure he had a lasting impact on UNM’s campus. Hibben died in 2002, and arranged for some of his considerable fortune to be donated to the university. Now, on the western end of campus, the Hibben Center for Archeology Research rises up like a temple to the man.

A local caving club volunteers time to clean up the trail and site. They also offer regular tours of the cave itself. (Photo: Ty Bannerman)

As the building was nearing completion in 2003, the journal Nature singled it out as emblematic of the kind of moral compromises universities make in accepting large donations. “Sometimes donations are made by individuals or firms who are seeking legitimacy after miring themselves in controversy,” the November 27 article, entitled “University buildings named on shaky ground” stated before referring to Hibben’s Sandia site discovery as “discredited” UNM professors at the time were quoted as stating that they only used Hibben’s findings as a way to teach students how not to do field work. A similar article appeared in the Guardian that same week. Titled “Dodgy donors embarrass scholars”, writers Robin McKie and Ben Wilson state that, although he was never publicly accused of fraud, Hibben was “known among colleagues for his decades-long habit of forging research results.” Despite the backlash, UNM completed the building and retained Hibben’s name.

These days, it’s not easy to find anyone at UNM who is willing to talk about these matters. After speaking to several current and former members of the faculty who refused to go “on the record” regarding Hibben, I tracked down Dr. David E. Stuart, author of Anasazi America, a renowned survey of early American inhabitants of the Southwest and many other books, who worked with him as a graduate student.

The spiral staircase makes for a dizzy, rickety ascent. (Photo: Ty Bannerman)

“Frank Hibben was an extraordinarily complicated figure,” he tells me. “He was a smart guy and a flamboyant guy. “

In Stuart’s telling, Hibben was, more than anything else, a victim of his own ego and propensity for exaggeration. “He was a teller of cowboy stories,” he says, adding that Hibben’s tall tales typically had a nugget of truth. “He was a showman… He added to his own legend, but that doesn’t mean there was nothing there!”

When I ask about the allegations raised in Preston’s 1995 article, the suggestions that Sandia Man samples may not have come from the Sandia Cave site, and the questions scholars raised about Hibben’s interpretation of the stratigraphic dating of the cave itself, Stuart sighs. There were two big problems, he says: turning over the Sandia Cave site to a graduate student (“he probably didn’t think there was going to be anything there”) and not opening up his findings to his peers, for review.

From Stuart’s perspective, it was this, combined with Hibben’s inclination to exaggerate that ultimately tarnished his legacy, as opposed to his committing outright fraud. “I view his archeological work as neither exemplary science nor completely craven,” he says.

Even so, I ask, given how controversial his legacy is, is it appropriate for UNM’s archeology program to build a monument to him in the form of the center that bears his name?

The cave extends some 140 meters back, but proper lighting and dust masks are essential for full exploration. (Photo: Ty Bannerman)

There is a long, pregnant pause as Stuart considers my question. Finally, he says in a very deliberate manner, “I do. But [UNM] may not be touting the right reason for having it.” Instead, Stuart says, Hibben should be remembered for his abilities as a teacher. “People loved his teaching. We used to have to get the fire marshal to clear the kids out of the aisles in the lecture hall,” Stuart says, “He was a faculty member who could motivate 500 kids semester after semester, year after year, generation after generation!”

A plaque once described Frank Hibben’s “discoveries” in Sandia Cave, but it has recently been taken down. (Photo: Ty Bannerman)

On a recent weekend, I went back to the cave to check on something that stood out in a previous visit, a bronze plaque that was bolted into a granite boulder near the cave entrance. It extolled Hibben’s discoveries and the legacy of Sandia Man. I was curious if, after all these years and the back and forth over the discoveries, it was still there. As I climbed up the snowy trail toward the cave, I almost passed the spot without noticing it. The plaque itself is now gone; all that remains is an empty black rectangle on the boulder’s face. In fact, Hibben’s name is nowhere to be found near the cave that, for better or worse, made him famous.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook