Facial Reconstruction, Nazis, and Siberia: The story of Mikhail Gerasimov

Mikhail Mikhaylovich Gerasimov was a Soviet archeologist and anthropologist who introduced major advancements to the field of forensic sculpture. He pioneered paleo-anthropological facial reconstruction of historic figures.

Mikhail Gerasimov hard at work in his studio, sculpting skulls from skulls. (source)

Gerasimov reconstructed the faces of more than 200 people, including Ivan the Terrible, Yaroslav the Wise, Tamurlane and Rudaki (founder of classic Persian literature).

Born in 1907 in St. Petersburg to a municipal doctor, Gerasimov’s father was transferred to Irkutsk, Siberia before the revolution. While Irkutsk was a site of many battles during the Russian Civil War, Gerasimov’s father was able to continue his practice.

Gerasimov’s interest in the intersection of sculpture and anatomy developed in part because of his father’s extensive library. Gerasimov began studying at the Irkutsk Medical School’s anatomical museum at the age of thirteen. He made his first sculptural reconstructions, those of the Pithecanthropus and of the Neanderthal, for the Irkutsk Regional Museum.

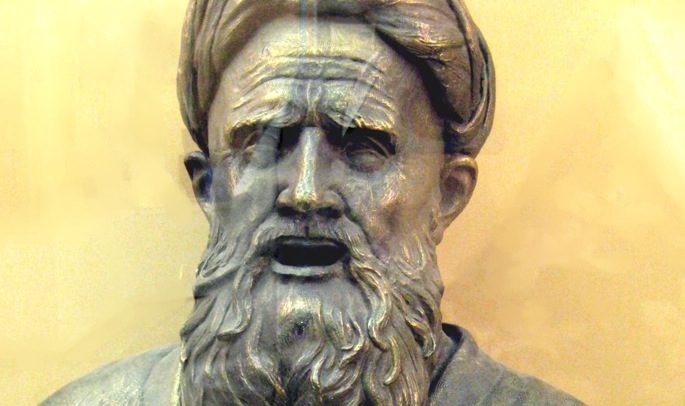

Gerasimov’s facial reconstruction immortalizing the Persian poet Rudaki. (source)

With years of practice, Gerasimov developed a deep understanding of the relationship between the skull and the facial soft tissues thanks to a combination of paleontology, archaeology, anthropology, and forensic science. Gerasimov’s meticulous workflow started with the restoration of the skull and the determination of the age, gender and individual characteristics of the cranium. He would then create a graphical reconstruction of the face, starting with the skull and adding on layers of facial muscles, the position of eyes, the nose shape and mouth shape. After the graphic reconstruction, Gerasimov would create the sculptural reconstruction using modeling putty.

Gerasimov’s responsibility for Hitler’s attack against the USSR is still a widely held belief in Russia and other post-Soviet states. While working at the Institute of Material Culture in Leningrad, he was commissioned by Stalin to lead an expedition to Uzbekistan to open the tombs of Tamerlane and other members of the Timurid Dynasty. Motivation for Stalin’s interest in this exhumation remains unclear.

The face that launched a thousand tanks: Timur (Tamerlane) himself. (source)

The religious leaders of Samarkand tried to stop the exhumation. The keeper of the memorial, Masood Alaev, translated the cautionary inscription carved on the jade tomb: “When I rise from the dead, the world shall tremble.” Even though Gerasimov was unfazed, word was sent back to Moscow, just in case. From there came the order: Arrest Alaev for spreading false rumors and panic, open the tomb immediately.

On June 19th, 1941 the huge slab of green jade sarcophagus covering Tamerlane was raised. Another inscription inside his casket read:

Whomsoever opens my tomb shall unleash an invader more terrible than I.

Nazi Germany launched “Operation Barbarossa” on June 22, breaking the earlier non-aggression pact between the USSR and Germany. Even though people close to Gerasimov claim that this story is a fabrication, the legend persists.

Gur-e Amir Mausoleum, Tomb of Timur. (source)

Tamerlane’s body was re-buried in the Gur-e Amir Mausoleum, under Islamic burial procedure in November 1942. The re-burial coincided with Operation Uranus in Stalingrad, which was the turning point leading to eventual Allied success on the Eastern Front. For the remainder of the war, Gerasimov remained in Central Asia working at the military hospital in Tashkent.

After the war, Gerasimov headed the Laboratory of Plastic Reconstruction at the Institute of Ethnography for twenty years until his death. He reconstructed the face of Ivan the Terrible in 1953. In 1961, Gerasimov travelled to Germany to help identify the scull of the poet Friedlrich Schiller in a mass grave.

.jpg)

Gerasimov’s Ivan the Terrible. (source)

After Gerasimov’s death, his students continued his work. His method has been instrumental in facial reconstructions of pharaohs. In 1991, Russian investigators also used Gerasimov’s method to clarify the identities of the remains of Nicholas II’s family. Gerasimov, a staunch atheist, would have probably been conflicted about the use of his method to approximate what Jesus looked like.

Gerasimov’s work can be seen at:

- Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography

- State Historical Museum of Russia

- Anthropological museum of Moscow State University

- Georgian National Museum

- Termez Archeological Museum in Uzbekistan

Further Reading:

- The Face Finder (Gerasimov’s autobiography)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook