The Italian Town Where You Can Eat Like a Renaissance Royal

Residents of Ferrara dine like 16th-century dukes.

Every morning by 3 a.m., at his shop in the northern city of Ferrara, Italian baker Sergio Perdonati recreates a Renaissance bread. Using a 90-year-old starter (which his father managed to save after the bakery was bombed during World War II), he rolls two lengths of dough, one beneath the palm of each hand, until they begin to curl. He then presses the two pieces together at the middle to form an “X” and pops it on a tray with a dozen others ready for baking.

With a texture like a soft breadstick, the coppia remains Ferrara’s favorite bread nearly 500 years after its invention. In fact, much of the city’s traditional cuisine is an ode to 16th-century cooking and the tastes of the city’s rulers at the time, the powerful Este dynasty. Ruling from 1240 to 1597, they transformed the city into a sophisticated artistic and cultural center. Their monumental castle still dominates the main thoroughfare and the collections of art they amassed fill the galleries. The tables of the epicurean Estes were also masterpieces, laden with sumptuous and extravagant dishes.

The city has endeavored to preserve the Este’s foods throughout the centuries as, like the artistic treasures, they represent Ferrara’s golden age. The residents of Ferrara have a penchant for pretending they are still living in the great Este era with reenactments of Renaissance parades and festivals. Recreating the food of the dukedom is a similar, albeit less extravagant, glorification of this great heritage.

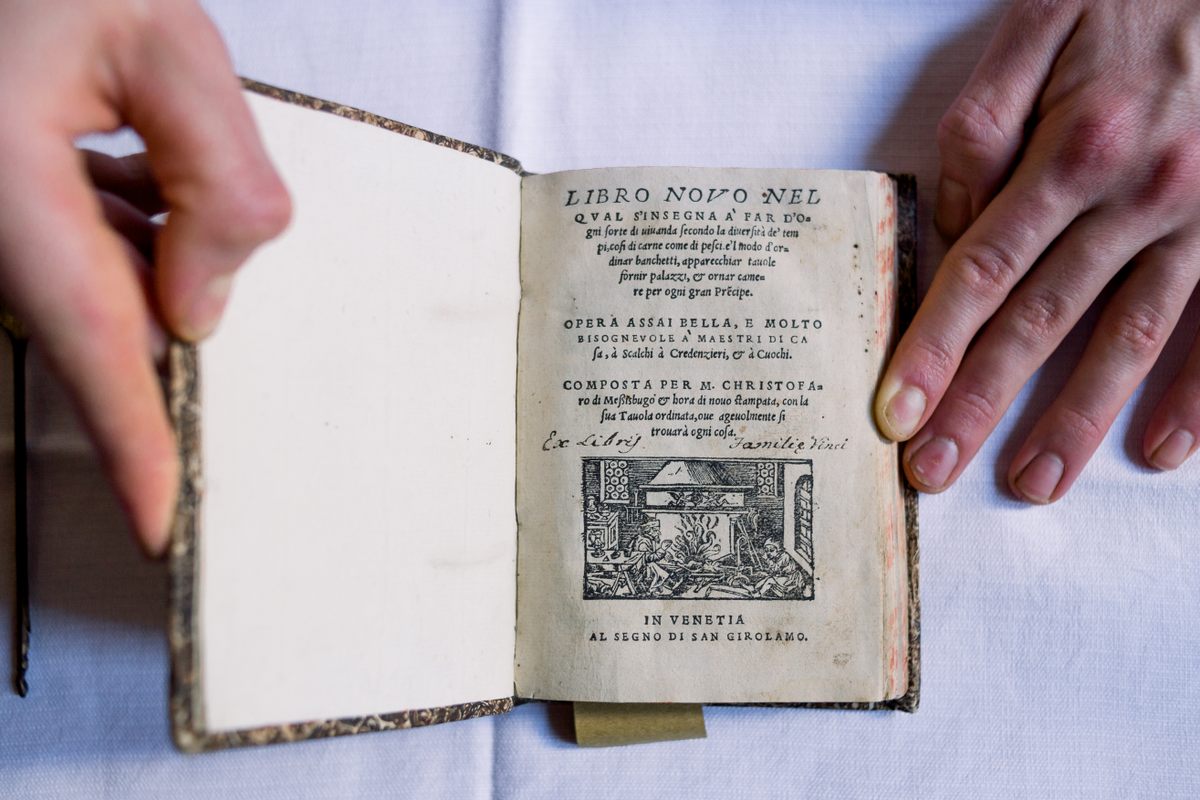

The origins of many dishes can be traced to the Estes thanks to the recipe book of the great court chef Cristoforo da Messisbugo, who died in 1548. Baker Perdonati explains that Messisbugo invented the coppia for a carnival dinner in 1536. The twisted form was supposedly intended to recall the luscious curls of Lucrezia Borgia, a noblewoman infamous as a femme fatale, whose third husband was Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara.

Nowadays, the coppia could be made with mechanical assistance for the mixing and kneading, but at Perdonati’s bakery, it is made rigorously by hand. That means each bread bears the “signature” of the baker who made it. “It’s a lot about technique,” says Perdonati, “you need two or three years to learn.” Under European Law, the coppia ferrarese has Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status recognizing it as a local specialty. Perdonati is passionate about sticking to the traditional recipe because “it is authentic and it is good for you, there are no additives like in modern bread.” The formula seems to be working, as his coppia flies off the shelves each morning and graces the tables of several restaurants in the city.

Also originating from Messisbugo’s opus Banchetti, Composizioni di Vivande e Apparecchio Generale (“Banquets, Recipes and Table-laying”) is salama da sugo, a traditional second course. To make this delicacy, various parts of a pig including cheek, tongue, and liver are minced, saturated in wine, flavored with salt, pepper, and nutmeg, and stuffed inside the pig’s bladder. This is then hung up to age for around a year. The cooking process involves boiling the salama for between four and eight hours. It is commonly served with potato purée, which helps moderate the powerful flavors of the meat.

At Ristorante Raccano, chef Laura Cavicchio serves the dish with an unusual, but once traditional, accompaniment. She adds a little cube of deep-fried custard sprinkled with icing sugar, which counterbalances the overpowering richness of the salama surprisingly well. Cavicchio has also recently given the archaic recipe a modern lift to ensure it remains popular. Her ravioli alla salama da sugo are pasta parcels stuffed with sweet potato and topped with a cheese sauce and a scattering of salama. It’s definitely less onerous than the original dish.

Cavicchio is constantly delving into historical recipe books (“I have a fire inside me,” she jokes), and she has resurrected another Messisbugo classic as a starter. Her crostini alla Messisbugo are triangles of toasted bread spread with chicken liver paté and aromatic herbs. “I translated and recreated the recipe myself,” she says, with obvious pride.

A dish that features almost ubiquitously on restaurant menus in Ferrara and is also frequently made at home is cappellacci di zucca—pasta parcels stuffed with pumpkin. The name translates as “little hats,” supposedly because their shape resembled peasants’ headgear. The recipe for this dish was first written in 1584 by Giovan Battista Rossetti, a “scalco” or member of a guild of gastronomic servants of the Este court.

Today’s recipe replicates Rossetti’s “Tortelli di Zucca con il Butirro” almost exactly. The filling, made from velvety butternut squash purée flavored with pepper and nutmeg, only omits ginger from the original ingredients. The stuffing also contains Parmigiano Reggiano or Grana Padano cheese, eggs, and breadcrumbs. The pasta parcels are served doused in butter and sage or in a meat or tomato sauce. At Ristorante Raccano, they are one of the best sellers. “Out of 100 people, 90 eat the cappellacci either because they are tourists who want to try it or because they are Ferrarese and they like it,” Cavicchio says.

But it is pasticcio, a centerpiece pie, that really feels like something resurrected from an Este banquet. At Trattoria da Noemi the hefty domed pie is decorated with strips, flowers, and an “N” from leftover pastry and is double egg-washed for a glossy finish. Inside is short maccheroni pasta with minced pork and veal and bechamel sauce in four thick alternating layers, flavored with generous shavings of black truffle. The full preparation process takes two days.

Maria Cristina Borgazzi, the daughter of Noemi, who opened the eponymous trattoria in 1958, has to make one of these colossal pies each day to satisfy demand. In order to keep the Renaissance recipe alive, Borgazzi took courses with local pastry chefs to learn the art of the pie lid. For the filling, she’s tweaked it a little, including omitting some of the more unusual spices, to ensure it would appeal to her modern diners. “It’s a delicate balance,” she says, “and with lots of time you work it out. That’s the idea of the pasticcio.” Though Borgazzi’s pie tastes exquisite, it’s inescapably heavy. But she laughs and remarks that for the Este, it would have been just one of up to 80 dishes at a banquet.

Borgazzi also prepares the 16th-century desserts, which are no lighter than the savory courses. One of them, torta di tagliatelle, also honors Lucrezia Borgia’s iconic hair. A shortcrust pastry case with almond and honey filling is decorated with delicate strands of crunchy pasta to mimic her golden locks. Borgazzi finishes off the dessert with a healthy dose of almond liqueur that sizzles as it hits the hot pastry.

Borgazzi explains that many of these Renaissance dishes have remained popular because they use local, easy-to-source ingredients. But more importantly, there is a distinct sense of pride in the historic cuisine (Borgazzi has Messisbugo’s cookbook in her kitchen). Echoing baker Perdonati, Borgazzi notes that food is as much a cultural treasure as the imposing Este castle that dominates Ferrara’s city center.

There’s plain evidence of this local pride during the festive period in Ferrara, when another Este treat, pampepato, fills market stalls in the central square. Nuns supposedly invented the spicy cake in 1660, drawing inspiration from a recipe in Messisbugo’s book. They named their creation Pan de Papa (Bread of the Pope), intending the sumptuous rich flavors to reflect the pontiff’s majesty. The inside is filled with almonds, hazelnuts, candied fruit, and spices, and the exterior is coated in dark chocolate.

Market stalls also sell local wines that, as expected, are sufficiently strong in character to match Ferrara’s cuisine. The Vini delle sabbie (Wines of the Sands) are again thanks to the Este, though with a little French influence. When Renata di Francia, daughter of Louis XII, married Ercole II, Duke of Este in 1528, part of her dowry was a vine of the Côte d’Or of Burgundy. The grape thrived in Ferrara’s sandy ground and the humid, salty air, producing a tannic, astringent wine that complements the meaty, rich cuisine.

Overall, it seems the only negative side effect of feasting like a 16th-century duke every day is somnolence. But the city has an antidote: nine kilometers (5.6 miles) of ancient walls encircling the city are preserved as a walking and cycling route, perfect for a post-prandial wake-up.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook