The Microscopic Majesty of Sugars, Salts, and Spices

A molecular biologist turned food writer put kitchen staples under the microscope.

While working on his upcoming cookbook, The Flavor Equation, food writer Nik Sharma packed up an array of salt, sugar, and spices and headed to the University of California, Berkeley. With the help of Steven E. Ruzin, director of the Biological Imaging Facility, he trained an AxioImager M1 microscope down at slides covered with brown sugar and kala namak, Indian black salt. With a ZEISS confocal laser scanning microscope, he peered down at bonito flakes and yeast suspended in vinegar.

These powerful microscopes revealed the razor-like ridges of Maldon salt and the fat, gem-like grains of brown sugar. The resulting photos make up a single spread at the end of his 352-page book. Nevertheless, both in his introduction to the book and over the phone, Sharma notes that including the super-zoomed-in photos was his “one dream.”

Though Sharma has been a food writer and columnist for years (currently with bylines in the New York Times, the Guardian, and Serious Eats), he started out as a molecular biologist, with a background in biochemistry and microbiology and a degree in molecular genetics. The Flavor Equation shows how Sharma has used his education. The book itself is replete with colorful diagrams that wouldn’t look out of place in a chemistry textbook and techniques such as one for making oven fries that Sharma adapted from blood collection. (Turns out, citric acid and sodium citrate, via lemon juice and baking soda, can both keep blood from coagulating and improve the texture of your fries.)

While Sharma has pondered a science-themed cookbook for years, from the beginning, he had a clear idea of what he would write: a cookbook that broadens the conception of food science beyond its narrowly Western focus.

“As someone who loves science and loves cooking, I have noticed always that there’s a very strong emphasis on European foods when it comes to food science,” he says. He’d never seen microscope photography of a number of his favorite ingredients.

It was this impulse that led Sharma to take his ingredients to the lab at Berkeley. The resulting photos reveal quite a bit about the qualities of the seasonings, all of which are used in various recipes in the book. There’s an enormous contrast between the defined shape of coarse salt and the fluffy-looking texture of kala namak. Sharma notes that the difference stems from the compounds that make up each. Most table salts are close to pure sodium chloride, while kala namak, mined from the earth and smoked, is made up of numerous other compounds that give it its unique properties. With its sulfuric chemicals, the black salt (which, despite its name, is red and not black) is often used by vegans to give foods a taste reminiscent of eggs.

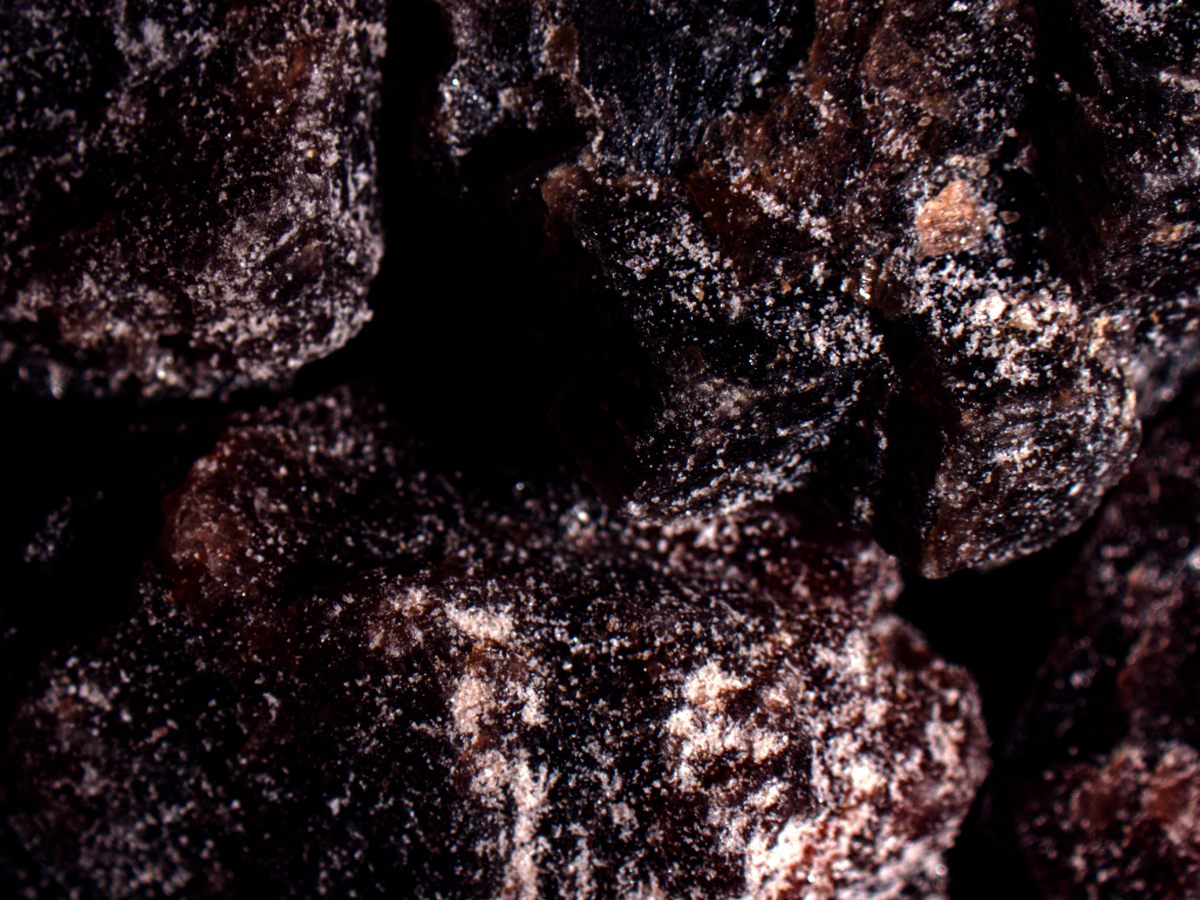

The same comparison applies to brown sugar and jaggery. Brown sugar is simply white sugar blended with molasses. The result, when viewed under a super-powered microscope, is large, distinct crystals. Jaggery, on the other hand, is much less processed. Boiled down from the juice crushed out of sugarcane, its relative complexity compared to brown sugar is obvious from its varied texture. “So it’s more of an amorphous powder,” Sharma says, as the additional compounds inhibit its ability to form a defined crystal structure.

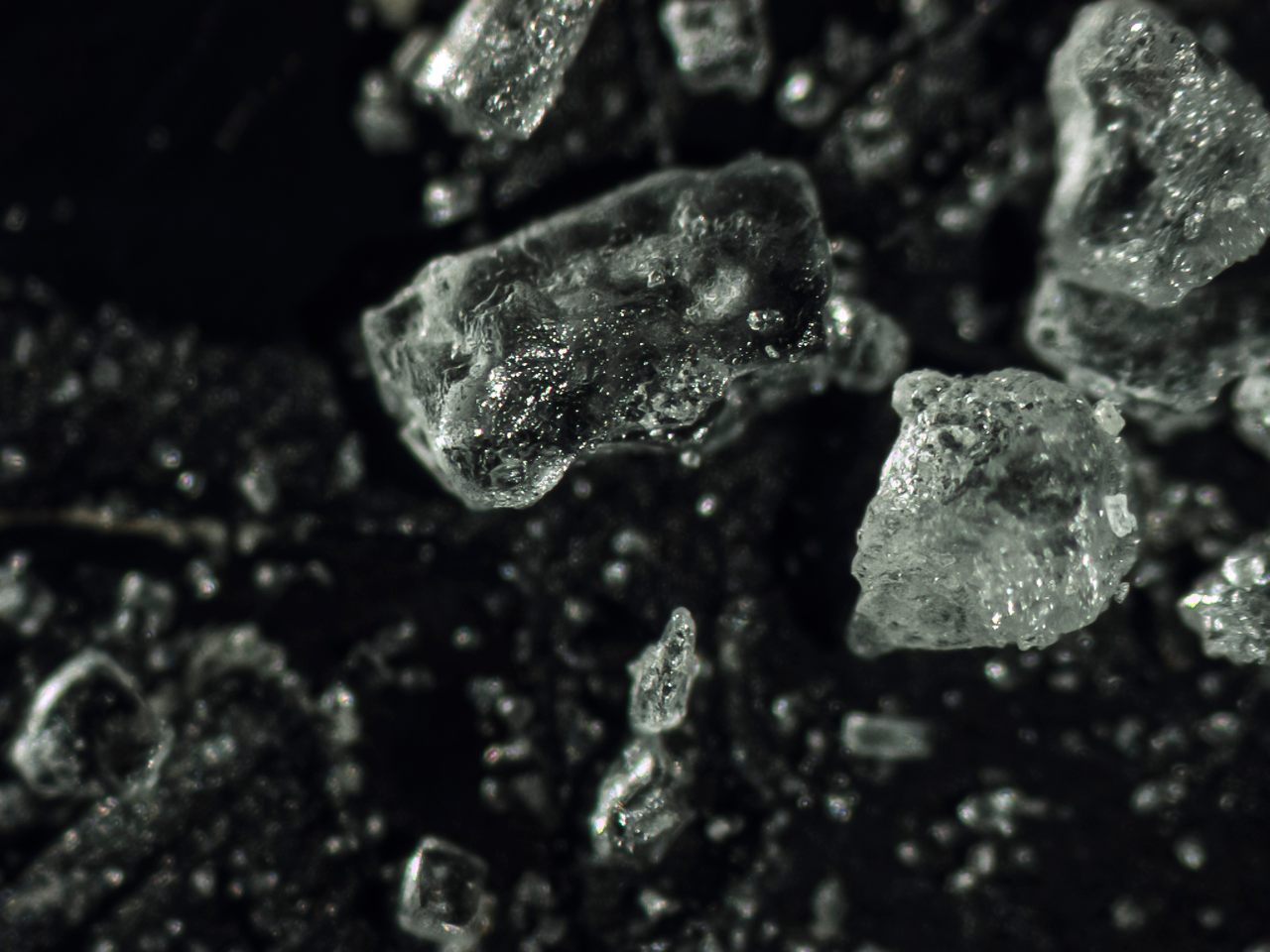

The shapes of seasonings do have an effect on cooking, Sharma says, though in many cases it may be too subtle for many people to notice. One example he gives is kosher salt, specifically the brand Diamond Crystal. “If you look under the microscope, it’s like teeny glass shards. It’s so flat and thin. So they dissolve really fast in water at room temperature.” Sprinkled on a steak, “you have more osmosis taking place with kosher salt because it’s dissolving faster on the surface.” The result, with the salt pulling water towards it quickly, is a better crust on your cooked steak.

Yet only a handful of the otherworldly seasoning pictures made it into Sharma’s book. For one thing, he had already gone 200 pages over his publisher’s limit, and many of the pictures weren’t quite the right resolution to print. In the end, he satisfied his scientific impulse with the other photos in the book. Sharma, a skilled photographer, took all the photos for The Flavor Equation. For many, he says, he wanted the illusion that he had taken them with a microscope, an effect he accomplished by using a huge homemade light box and glass plates. The cover sports an image of lime slices laid flat, their segments as distinct as panes of stained glass, and a photo of a pool of oil, for a chapter on “Richness,” is so zoomed in that you can count the bubbles.

While Sharma has dreams of buying a microscope for more food photography, there’s a reason he had to go to a special lab for these pictures. (Said scopes are wildly expensive.) “So this is the best that I could do, in my own way,” he says, to show people the unique geometry of the ingredients they use every day. “It’s not like science only applies to European food,” he states. “It also applies to other cultures.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook