One of Hawaiʻi’s Rarest Bogs Just Got an 11-Year Makeover

Step 1: Evict all the pigs.

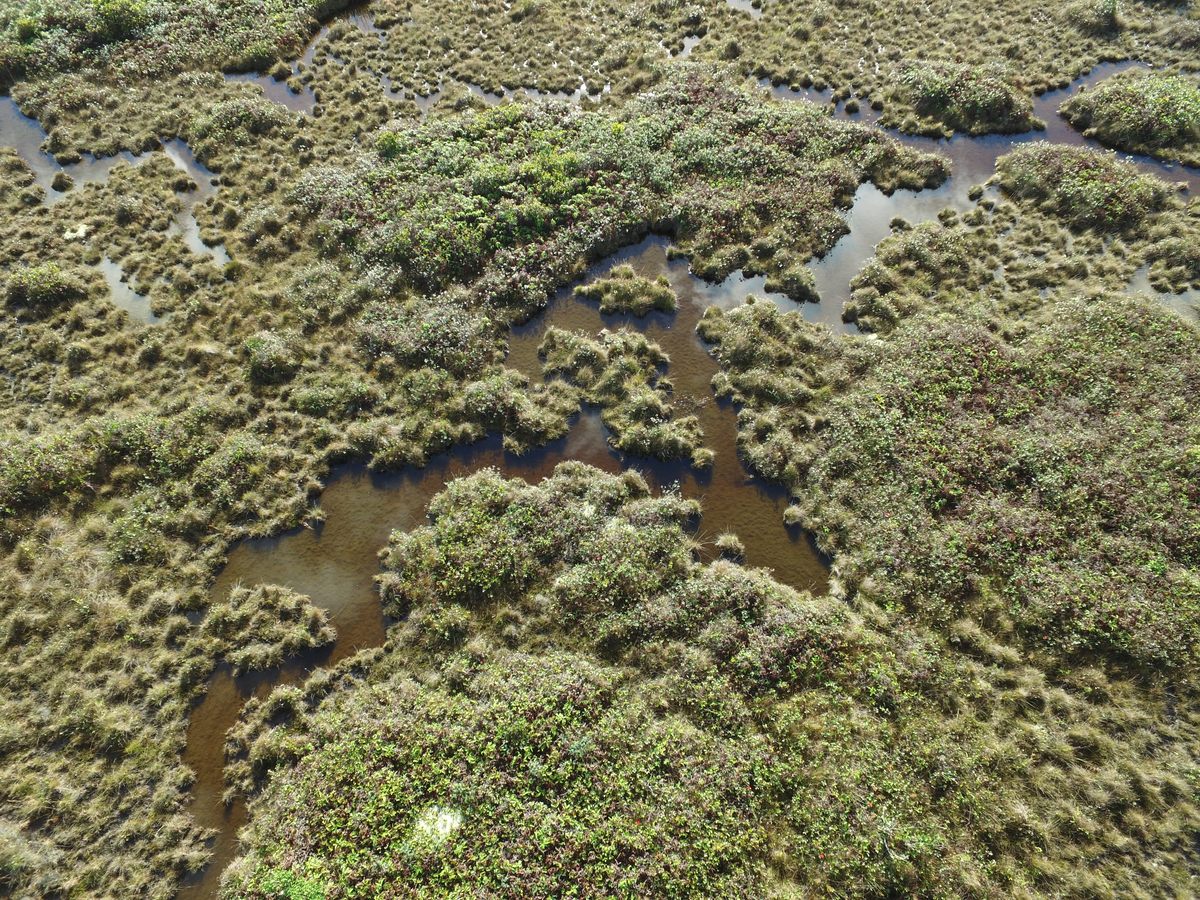

For years, the Kanaele bog didn’t look like itself. Instead of its characteristically, consistently moist, spongy ground, the bog brimmed with muddy, misshapen puddles. In place of a natural garden of native flowers and grasses, ferociously invasive strawberry guava trees sprouted at every turn. And there were no white-tailed tropicbirds circling overhead, just feral pigs trampling the ground and fiending for food. It was a fallen bog.

Kanaele is an unusual bog for Hawaiʻi, which makes it a rarity among rarities. It is the state’s only lowland bog ecosystem (the uncommon others are montane), Kanaele was a natural gem—at least if you’re a bog scientist, and before it was overrun with non-native plants and feral pigs. But now a cleanup project, 16 years in the making, has restored Kanaele to its former quaggy glory.

Nestled deep within the amphitheater of the lime-green mountains in southern Kauaʻi, Kanaele is hard to get to—which isn’t actually inconvenient, as it’s not open to the public. The bog is tucked away behind the town of Kalaheo at an elevation of 2,100 feet, accessible only by winding private roads that demand four-wheel drive. The land Kanaele is on is owned by the real estate company Alexander & Baldwin, which recognized the sorry state of the bog and signed a 10-year management agreement with the nonprofit The Nature Conservancy (TNC) to get the ecosystem back on track. The Kanaele preserve is also a part of the Kauaʻi Watershed Alliance, a public-private partnership of landowners committed to protecting Kauaʻi’s watersheds.

The challenge was enormous, mostly because of the pigs. Pigs love bogs because pigs love digging, and moist bog soil is more snout-friendly than the dry, hard sort. Hawaiʻi’s feral pigs aren’t the soft and lazy type. Bristly, and sometimes with an intimidating set of tusks (the better for destructive digging), they had done a real number on the bog. Tasty native plants had evolved to grow without large grazers and rooters such as pigs, and therefore never needed the kind of evolutionary trickery that other plants developed to stay alive, according to Melissa Fisher, the director of TNC’s forest program in Kauaʻi. “Hawaiian mint is mintless,” she says, by way of example. “It’s part of the mint family, but it doesn’t smell like mint. So pigs love it.”

And even after the foraging ferals move on, their snouts and hooves leave behind mud puddles that disrupt the bog’s hydrology and become prime breeding ground for mosquitoes, which carry diseases fatal to the island’s native honeycreepers. The small birds pollinate native plants such as the ʻōhā wai, or the Pele lobeliad, a sizeable shrub with talon-shaped flowers the color of ripe eggplant. The pigs are basically a perfect storm of bog insults.

“We knew we’d lose the battle until we removed the feral pigs,” Fisher says. So TNC members and volunteers built a sprawling, 6,552-foot-long protective fence around the 57 acres of Kanaele. The fence is made of rather aptly named hog wire.

After the bog was safely enclosed and pork-free, it was time to weed. The main perpetrator was the fragrant, deceptively attractive strawberry guava plant, or Psidium cattleianum, an invasive species that has decimated Hawaiian forests since it arrived on the islands in 1825. Strawberry guava, though charming, is also almost impossible to kill. It produces sweet fruit beloved by animals (including humans). “Pigs love it, birds love it, and humans love it,” Fisher says. “So it definitely outcompetes native plants.” Strawberry guava is also a sneaky invader, as it can grow multiple trunks from just one plant. As the invasive weed specialist Chuck Chimera told The Atlantic, the plant is just like the Hydra: “Cut off its head and five or 10 will spring up in its place.”

So it wouldn’t be enough to rip the plants out by their roots. Instead, Fisher and the other weeders used knives to feather the bark of the plant and apply a tiny drop of herbicide on each one, usually dyed bright pink or blue. But it’s a delicate process. “We’re very careful with the amount we use,” Fisher says. “We measure all the herbicide to know how much is used in an area because we have to be careful not to kill native plants.”

One of the hardest parts of the treatment plan was merely getting around the bog, especially without causing further damage. For all their ecological fragility, bogs are more treacherous than they appear. Fisher and the other volunteers had to walk around the fenced perimeter of Kanaele before venturing to an area deeper in the bog. “It’s quite wet and spongy,” she says. “If you’re not watching yourself, you could sink up to your knee.” After marking a plant for death, the weeders documented the areas they covered in a geographical information system to determine where they would need to re-weed in the future. Weeding is never a thing you do just once.

Since the weeding started in 2008, TNC has removed more than 90,000 plants from the bog, 82,437 of which were strawberry guava. Other offenders include the Asian melastoma, a shrub with purple flowers, and clidemia, a densely thicketing plant with shiny leaves. In Hawaiʻi, it seems, even the weeds are pretty. But once the pigs and alien plants were gone, Kanaele began to replant itself with what thrived before. “It’s not restoration work in the sense of planting plants, but taking away the threat,” Fisher says.

When the restoration began, Fisher and the TNC team weeded every few weeks. Now they only need to return three or four times a year. Under the guidance of TNC, Kanaele has once again become Hawaiʻi’s last intact lowland bog. All the others had already been trampled out and overtaken beyond the point of saving.

In its natural form, Kanaele is precious in part because so many of its lifeforms are miniaturized. The ground is both waterlogged, from the 160 inches of rain it receives each year, and unusually acidic, conditions that stunt the growth of the various species of flora that make their home there. Many of the species that grow in these conditions exist in no other habitat in Hawaiʻi, or any other bogs around the world, for that matter. Healthy Kanaele now swarms with low-lying species, such as native grasses, sedges, mosses, and lichens, as well as dwarfed trees such as the ʻōlapa, a flowering ginseng, and the modest green shrub hame and the Pele lobeliad. A refuge for the lobeliad is particularly welcome. Of the 126 species of lobeliads native to Hawaiʻi, half are endangered and as many as 20 may be extinct, according to Keola Magazine. The critically imperiled Viola helenae, or Wahiawa stream violet, has also returned to Kanaele. These bog-based violets can grow up to two-and-a-half feet tall,* and only thrive in two known wild populations.

The most famous among the bog’s native flora is the mikinalo, or carnivorous sundew. Though the mikinalo is found in Japan and southern Europe, the Hawaiian population is a subtropical variant that grows much smaller and does not experience a winter dormancy period. On Kauiʻi, mikinalo are diminutive—just around two or three inches tall—and delicate predators that feed on insects. Bugs are drawn to the mikinalo’s nectar, which functions as a glue trap. Then tiny fuschia mucilaginous tentacles—yes, they’re really called tentacles—carry more and more glue until the critter is covered, consumed, and digested. Mikinalo often grow nestled among the spiky shards of native sedges, where it can be spotted with its hot pink tentacles.

Since the initial phases of the project were completed sometime around 2015, when Fisher returns to weed a little more, she’s been astonished by the native species that have returned, and ones that just pass through. She’s noticed native damselflies buzzing around streams and the migratory Pacific golden plovers hopping around the misty ground. This year, she even swears she spotted a pueo, the elusive Hawaiian owl, endemic to the island chain. And when she steps outside the fence to lock up Kanaele—the fence will remain as long as the pigs do, which seems to be forever—the water running out of the bog is no longer muddy, but clear. “These areas can change,” she says. “They can heal themselves.”

* Correction: This post previously stated that the Wahiawa stream violet grew up to 26 feet tall. It actually grows two-and-a-half feet tall.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook