How Historical Societies Are Bringing Their Recipes to Pandemic Cooks

Food has become an important tool for connection.

Kayla Chenault and Dean Nasreddine had spent months planning a murder-mystery experience inside the Detroit Historical Museum. As the Detroit Historical Society’s education-programs coordinator and community-outreach coordinator, respectively, they had imagined a party, set at the height of Prohibition in 1926, where guests in period attire would enjoy cocktails and hors d’oeuvres while learning about Detroit’s wild and wooly bootlegging days.

But on the day the event was meant to take place, the state of Michigan handed down a different prohibition. Due to the spread of COVID-19, large gatherings were no longer permitted.

Museums and historical societies across the country faced a similar situation. By closing their doors and cancelling long-planned programs, they lost their primary means of engaging their communities. So, as cooking at home became increasingly important, many historical societies turned to sharing historical recipes from their archives. Though these cultural institutions don’t normally focus on culinary matters, they found that food and drink offered a delicious distraction from the present.

Detroit Historical Society’s “Pint-Sized Prohibition”

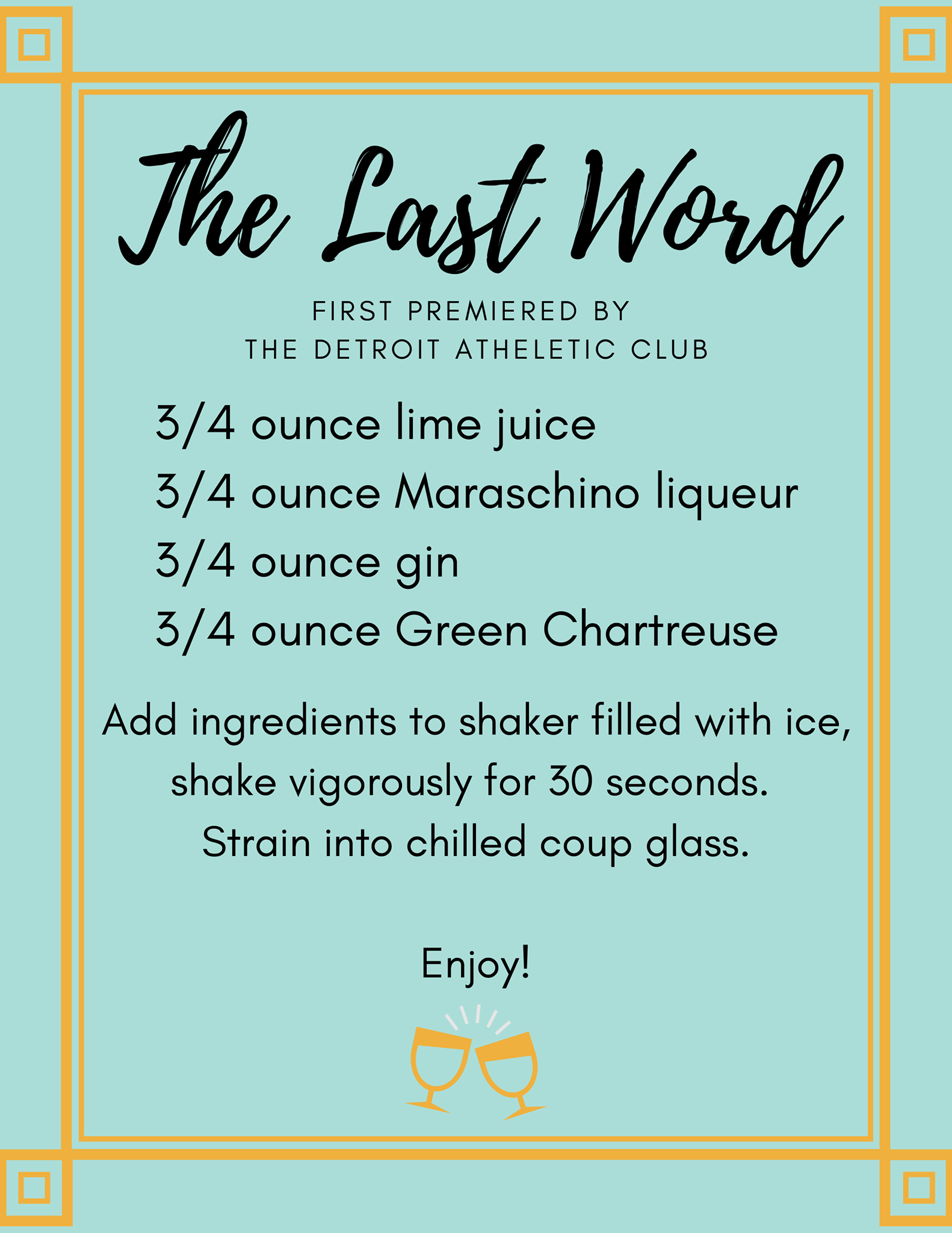

Chenault and Nasreddine are still channeling 1920s Detroit, this time by sharing cocktail recipes. Filming over Zoom, they’ve launched a video series called “Pint-Sized Prohibition” that combines local history vignettes with drinks dating to Detroit’s early-20th-century splendor. In their first episode, they introduced the Last Word, once one of the most popular drinks in the United States, says Chenault. Created at the Detroit Athletic Club pre-Prohibition, it’s a delicate-looking concoction of gin and green Chartreuse, soured with lime juice and decorated with a Maraschino cherry. (The duo did not include a recipe in their second episode, about the temperance movement, because Chenault says that would be “a little weird.”)

Though their event was cancelled, Chenault hopes that their loving tribute to Detroit’s past will offer a sense of togetherness, in a time when many feel isolated and uprooted. Historical recipes with local roots can “help people feel like they’re part of history and feel connected, even if they’re far apart,” she says.

Oregon Historical Society’s Chocolate-Nut Cake

The Oregon Historical Society, which also comprises a research library and museum, is unlikely to hold their sixth annual Celebrity Chocolate Cake Smackdown, in which local luminaries compete for the approval of Gerry Frank, the nonagenarian judge of the Oregon State Fair’s chocolate cake contest.

But Katie Mayer didn’t have the yearly competition in mind when she developed a cake-baking challenge as a way to connect with her far-flung coworkers, after the institution shut its doors on March 13. Mayer, who loves to bake when she’s not overseeing the OHS’s records and catalog as the technical services librarian, asked her coworkers to prepare a chocolate-nut cake recipe from a cookbook published in the town of Newberg, Oregon, in 1912, with a secret ingredient: mashed potatoes.

Eleven of her co-workers volunteered to bake the cake. The recipe itself is brief, and includes no baking instructions. “Women of that era did not really need instructions, because they learned to cook from a really young age,” notes Mayer.

Historical recipes, Mayer cautions, sometimes stayed historical for a reason. “The reaction to how the cake tasted was not overwhelmingly positive,” Mayer says. Many of the participants ended up icing their cakes or adding berries for extra flavor, since the cake itself doesn’t call for much in the way of chocolate. Afterwards, Mayer posted the cake photos and the recipe in an OHS blog post, inviting followers on social media to make their own mashed-potato chocolate cake. “We all made this cake. And, of course, what we got out of it was 12 different cakes,” she says.

Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s Foodie Friday

While the OHS’s cake-baking project was a one-off, other historical societies are publishing weekly recipes on social media. At the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the preparation for their Foodie Friday project was underway even pre-pandemic, says Christopher Damiani, the programs and communications manager at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Planned by conservator Tara O’Brien and her team, the HSP’s Facebook and Instagram pages feature historical recipes from cookbooks in the society’s library, prepared by the staff, once a week. “We wanted to make sure that we spread the word that the HSP does have more than just founding documents, although those are very important,” Damiani explains. (Their library is home to the first draft of the United States Constitution and a printer’s proof of the Declaration of Independence.)

Each Foodie Friday recipe at the HSP features a printable recipe sheet, with the original text and notes for the modern cook. The recipes were deliberately chosen to showcase the breadth of the recipes in the HSP’s collections. They span the work of Ellen Emlen, a Philadelphia housewife who in the mid-19th century recorded around 200 recipes, to a coffee recipe from the papers of William Penn, the founder of what would one day become Pennsylvania. The brew is spiced with saffron and rosemary.

New-York Historical Society’s Recipe of the Week

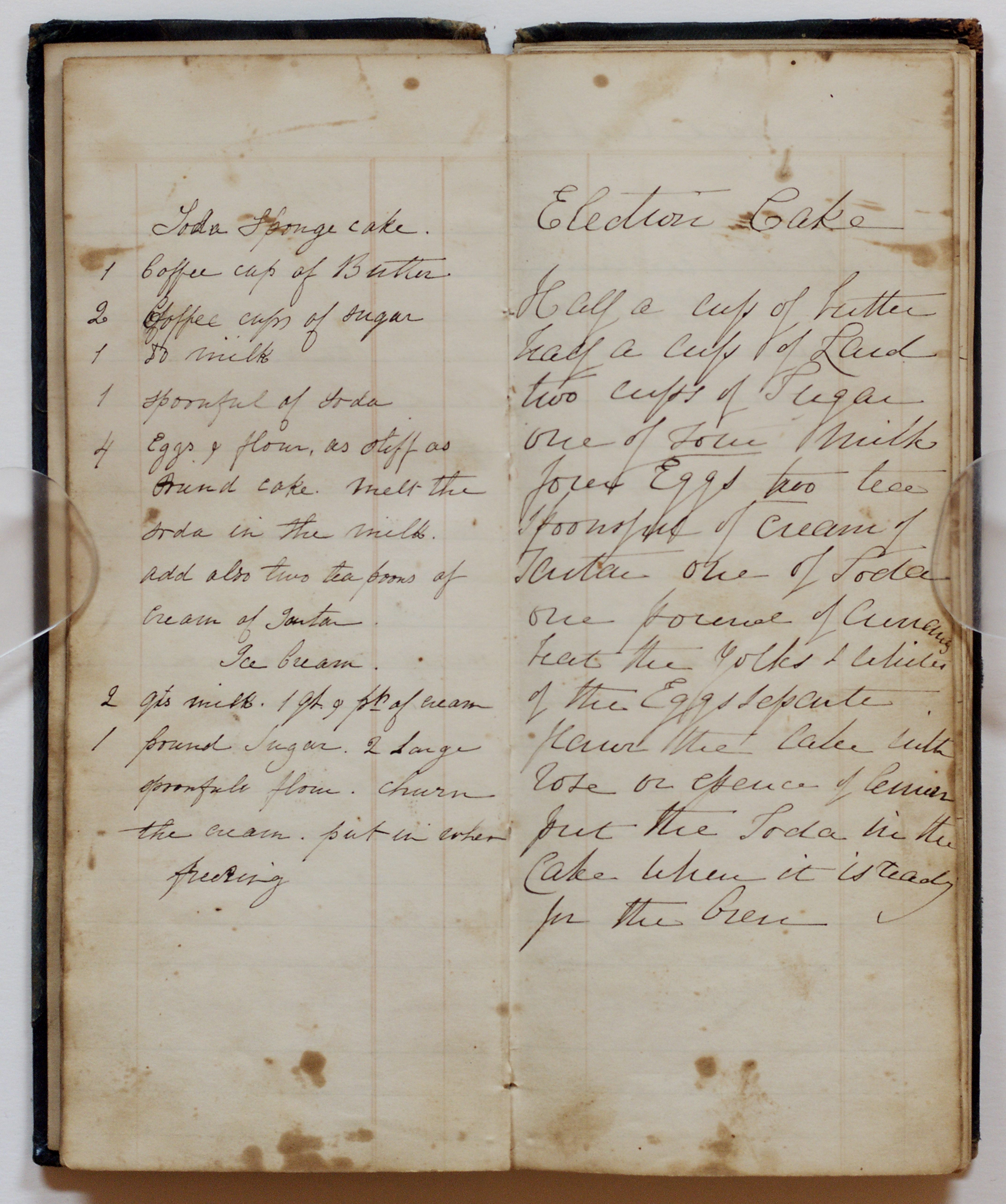

Even the most hardcore historically minded cooks might balk at making a 30-gallon cask of spruce beer. But the New-York Historical Society has a recipe for you anyway. They’ve been sending recipes to newsletter subscribers weekly since early April. But while a 19th-century lemon cake with no instructions or early brownies to be cooked in “a hot oven” might require a bit more eyeballing than usual, many of the foods they feature call for simple ingredients that would have been available to cooks more than a century ago.

Most of the recipes are sourced from the Duane Family Cookbooks, says Louise Mirrer, the Society’s president and CEO. Members of the Duanes, a prominent New York family, recorded a number of recipes in the mid-1800s, ranging from Election Cake to a cholera remedy. “It reminds people that New York has been the epicenter of many epidemics,” says Mirrer.

As adorable and well received as recipe-based programming has proven, it can’t fix the damage that has been done to many of these organizations by the pandemic. Much of the staff at the HSP has been furloughed, and Mirrer laments that four exhibitions had just opened before the New-York Historical Society closed its doors on March 13.

Still, as people seek out connection and comfort, food can prove an important tool for outreach. Mirrer notes that the New-York Historical Society’s revenue stream has dried up almost completely—except for donations. “So it’s been very, very important to establish a personal connection with people who then will want to support you,” she says. “And so many people tell me that they look forward to the recipe of the week.”

Early on in the pandemic, Mayer, who lives alone, found the experience of baking by herself “strange and isolating.” But finding an unusual recipe and sharing it with co-workers and OHS membership was a rare opportunity for indoor adventure. Comparing notes on frosting and dry cakes, “we suddenly all had this thing to talk about,” she says. “That felt different from the grind of day-to-day life, during a pandemic.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook