History’s Greatest Potato Promoter Relied on Science and Stunts

Before Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, the French considered the tuber disgusting and poisonous.

Neither prison food nor Prussian food have a great reputation, but during the Seven Years War, the combination made quite an impression on Antoine-Augustin Parmentier. Born in 1737, he became a pharmacist in the French army and spent three years as a prisoner of war. The prison diet consisted largely of potatoes, which the Prussians cultivated but the French viewed with disdain. Once freed, he made the potato his obsession.

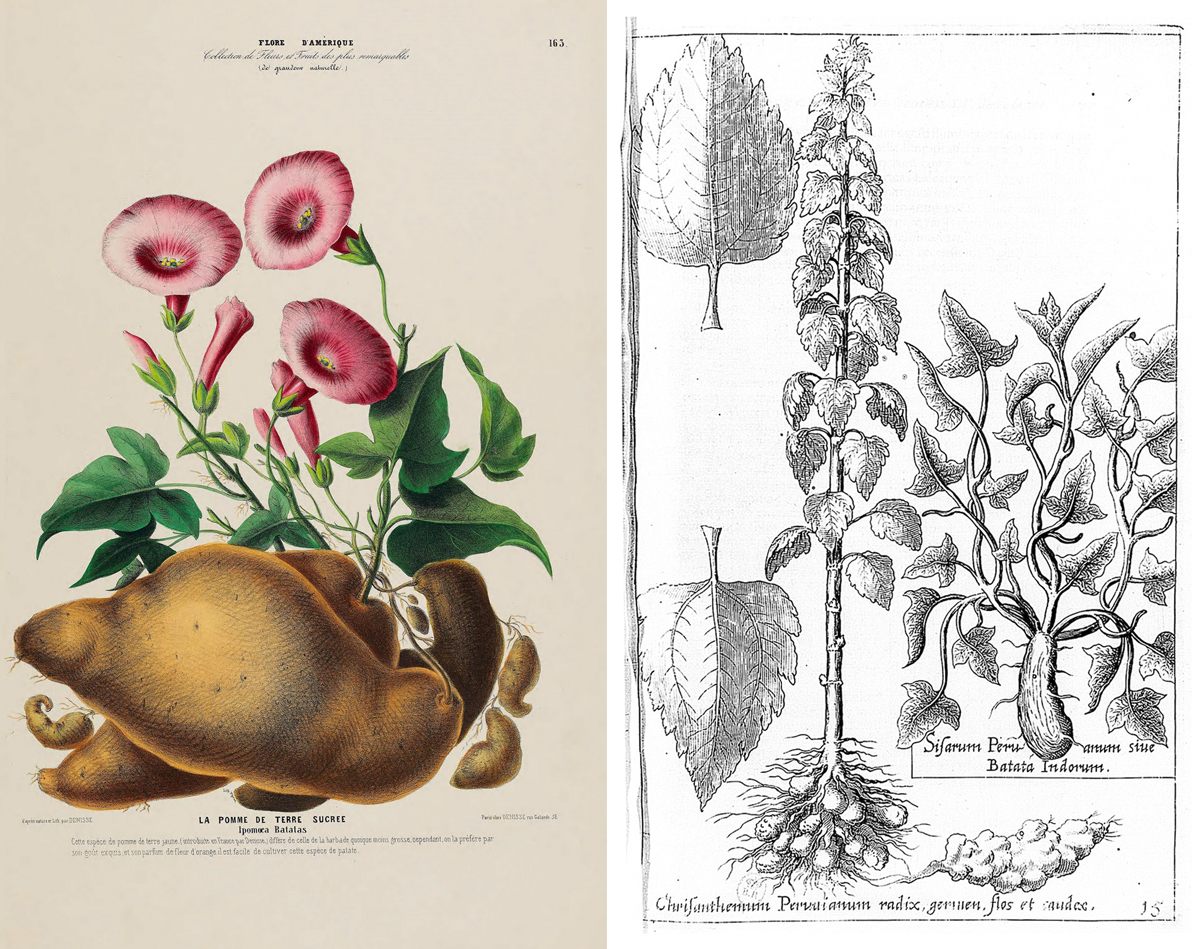

While the spud had crossed the Atlantic (from its native South America) in the late 1500s, it was viewed with suspicion in many European countries. In France, it was fed to pigs but considered suspect for human consumption. Superstition held that it was poisonous or caused leprosy—based on gnarled potatoes resembling the stubbed appendages of lepers. The fact that potatoes grow underground, and not from seeds but from chunks of the tuber, also darkened its reputation. Potatoes weren’t sold or grown in any great volume.

But after returning from three years of the potato diet with his health intact, Parmentier set to work to prove that his own experience was no anomaly.

“That’s very typical of the period,” says historical novelist Catherine Delors, who blogs about the 18th century, “when you have the flourishing of the sciences and people challenging old ideas.” This was during the Enlightenment, and experimentation and research was becoming the new norm. By combining this scientific outlook with a flair for showmanship—including publicity stunts—Parmentier put potatoes on European plates and had a dramatic effect on world history.

Parmentier started by going to scientific institutions and the Faculty of Medicine in Paris. He wanted, says Delors, “an official statement that potatoes were not as dangerous as they had been believed to be in France.” Famine was a recurring problem, and after 1770’s failed harvest, the Academy of Besançon offered a prize for proposals to address the problem. Parmentier won with his potato-propounding essay “Inquiry into Nourishing Vegetables That in Times of Necessity Could Substitute for Ordinary Food,” which he then expanded into a more thorough examination of the potato’s potential.

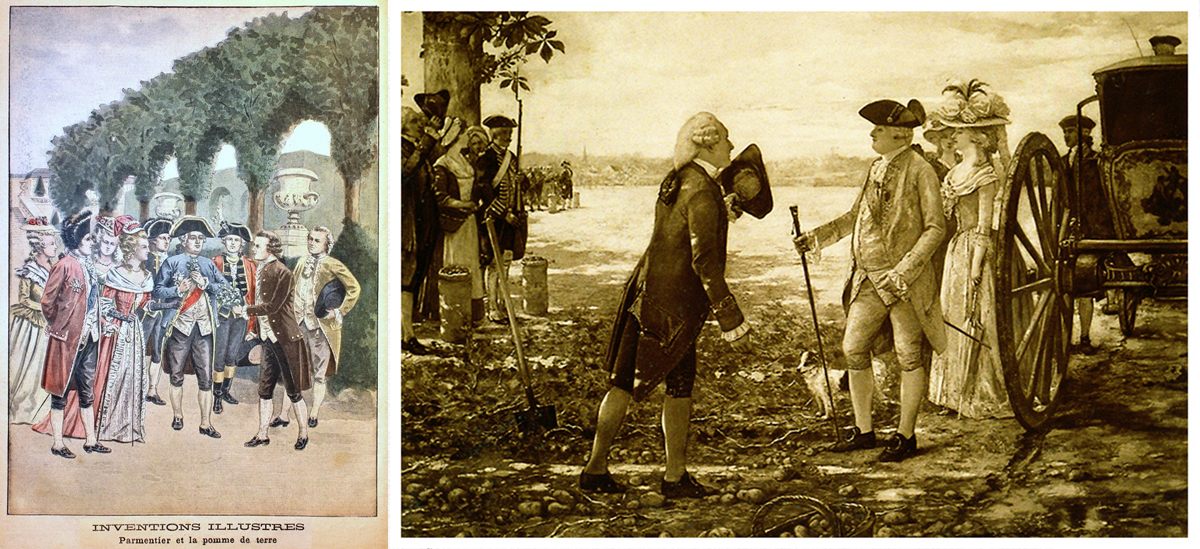

While his work conformed to the relatively new scientific rigors of his day, his public efforts to build awareness of the potato were splashier. Both Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson attended his potato-centric dinners, wherein the potato featured in different guises over as many as 20 courses. A copy of Parmentier’s treatise found its way to Jefferson’s library at Monticello, and it may be that Thomas Jefferson brought what would become the French fry back with him and served it at a White House dinner.

Parmentier even solicited celebrity endorsements. After a meeting with King Louis XVI, His Majesty and Marie-Antoinette are said to have adorned their outfits with the purple flowers of the potato in their lapel and hat, respectively. In 1886, royal support also included a plot of land to grow potatoes in Sablon, then on the western edge of Paris. Parmentier hyped his urban farm project by hiring guards to watch the plot, creating the impression the potatoes were valuable. Intrigued cityfolk could nonetheless surreptitiously help themselves to “free samples” when the guards retired for the evening.

Farmers’ adoption of the tuber—in the wake of Parmentier’s P.T. Barnum-esque stunts—had a profound impact on history. The potato radically altered the productivity of French farms. Its yields were more reliable than those of wheat, and it could be grown in wheat fields while they lay fallow. It prospered in many different soils and was easy to farm. And in other countries, leaders such as Catherine the Great (Russia) and King Adolf (Sweden) promoted the tuber for similar reasons. By some estimates, potatoes doubled Europe’s food supply in terms of calories, effectively marking an end to the cycle of plenty and famine that had tormented European agriculture for centuries.

While Parmentier was an effective potato promoter, his message resonated because it fit the needs of the time. “Parmentier’s message and enthusiasm are genuine,” says Charles C. Mann, author of The Wizard and the Prophet, which details the roots of the Green Revolution. “But he gets attention because people are casting about for ways to improve agriculture. The state was very interested in martialing up big populations so they could have lots of soldiers and workers.”

Famine was previously seen as a fact of life, says Mann, and Parmentier became part of government efforts to change that. France and other European states were beginning to institutionalize food production. In hopes of creating a healthy population of workers and soldiers, they encouraged mass production of desirable crops and subsidized and supported farmers. The resulting population boom in Europe, fueled in part by the dependable, productive potato, fueled European expansion and colonization across the globe.

The king himself acknowledged Parmentier’s efforts, granting a sinecure in 1774 to allow him to conduct his research and eventually telling him, “France will not forget you found food for the poor.” That royal connection cost him dearly during the early years of the French Revolution, when much of his property was seized. But he returned to society relatively quickly. The revolutionaries, after all, had their own interest in feeding the populace. Parmentier’s job security grew during Napoleon’s rule, as Bonaparte wanted to ensure French self-sufficiency while it waged war across Europe. Parmentier’s work by then included researching beet sugar and corn. Napoleon eventually granted him the Legion of Honour.

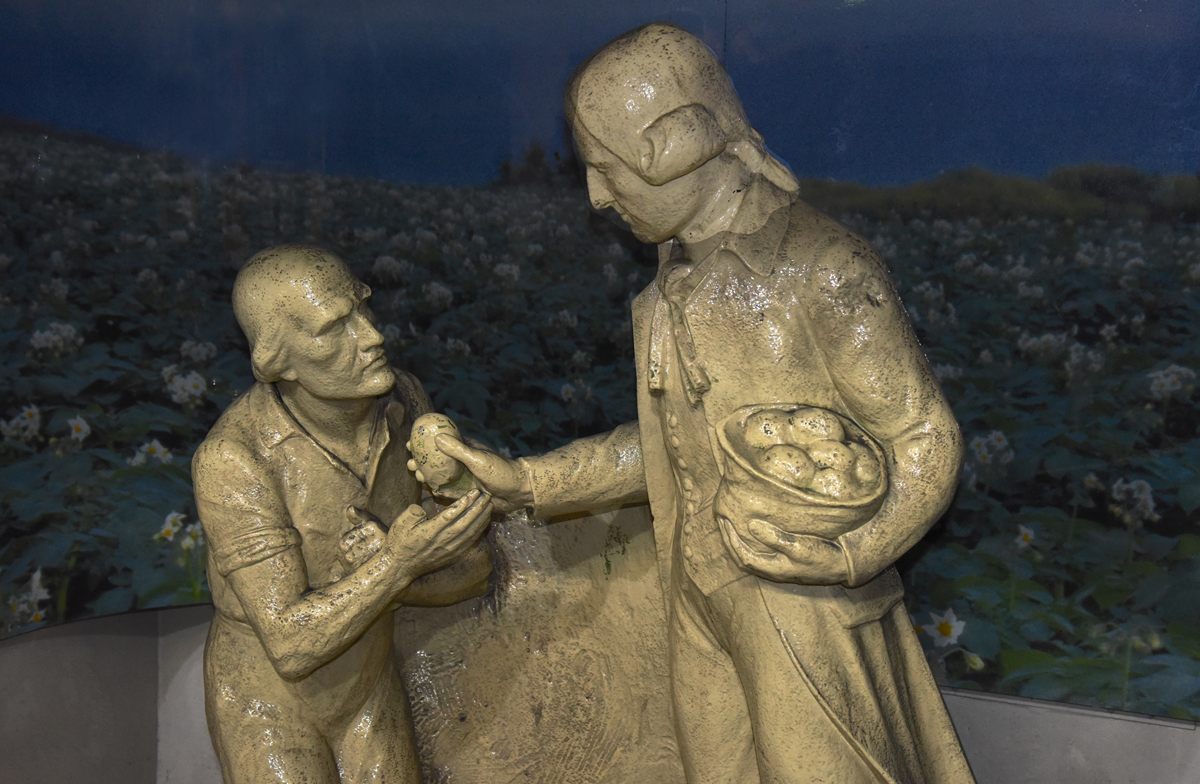

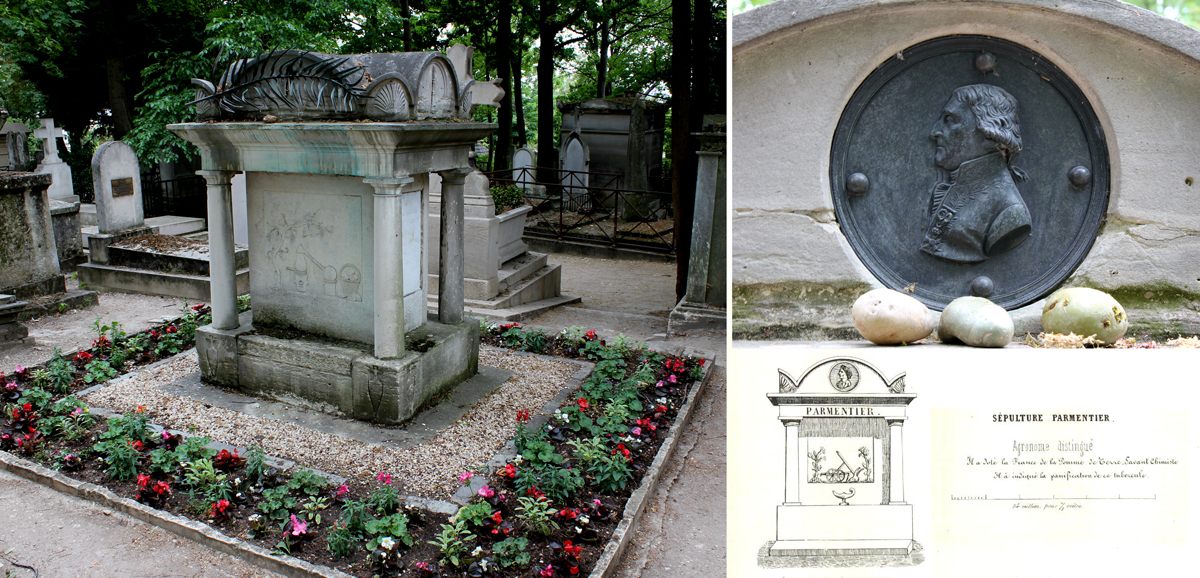

Parmentier is still well known in France, where he is remembered as a kind of Johnny Appleseed figure. A number of dishes include his name, which is a sign that potatoes are present: Hachis Parmentier is a sort of shepherd’s pie of ground beef topped with mashed potatoes. You can also find statues of Parmentier in the Somme, France, and the Parisian metro station that bears his name, which depict him nobly holding forth a potato. When he died in 1813, he was buried in Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Even today, his plot is surrounded by potato plants, and the occasional tuber is left on the grave of the great potato promoter.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook