To Make Japan’s Original Sushi, First Age Fish for Several Months

Or even years.

In the Japanese city of Wakayama, a stone’s throw away from ancient castle ruins and the Kumano river, a 74-year-old restaurant called Toho Chaya specializes in an ancient form of sushi. To make narezushi, the restaurant packs rice inside salty fish carcasses and ages them for months. Toho Chaya has always done things the old-fashioned way, from making narezushi to conducting an interview by fax machine. “Since it is made by fermentation, it tastes similar to cheese or yogurt,” writes chef and owner Ikuo Matsubara via fax.

And if that wasn’t intense enough, for the equivalent of $53 US dollars, Toho Chaya serves a small jar of 30-year-old aged sushi, so decomposed that it’s texturally more of a thick gruel than a modern-day sushi roll. While some chunks of fish still keep their shape, time and bacteria liquefies the mixture to the point that it can only be used as a condiment. Sour, pungent, and mildly sweet, it’s eaten atop tofu or rice.

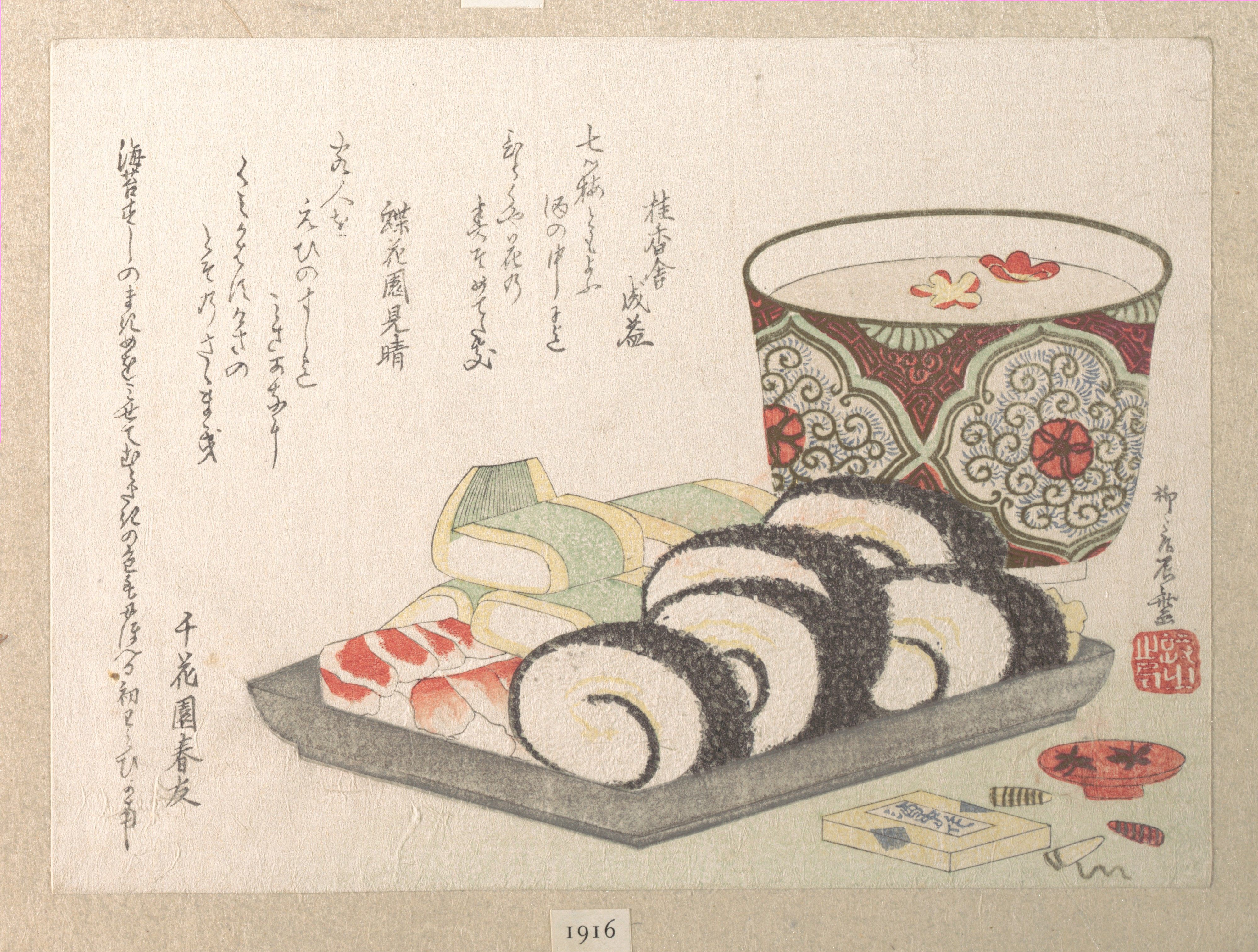

Modern-day sushi is often synonymous with raw fish. But the type of sushi that we know and love today is actually a relatively recent invention, only emerging in the early half of the 20th century. Sushi itself, however, has been around for centuries. The word sushi is derived from the Japanese word for sour, and its earliest form—narezushi—is pickled for months or even years.

First recorded in Japan in the 8th century, narezushi is considered a delicacy today because of how long it takes to make. But this preservation technique was originally born out of necessity. Before refrigeration, making narezushi was the one of the best ways to preserve seasonal fish throughout the year.

First, cooks salt the fish, killing microbes on the surface and allowing salt-tolerant lactic acid bacteria to flourish. When the fish is packed with rice, the lactic acid bacteria consumes the sugars and produces sour lactic acid. The acid lowers the pH of the entire dish and keeps it from spoiling. This same microbial process is used all over the world to make pickles and other fermented foods.

Narezushi’s texture and taste is completely different from the modern sushi roll. “There are different taste sensations, mostly based on how thick the fish is sliced. If it’s sliced very thin, then it’s like a prosciutto. If it’s thick, it’s more like a summer sausage,” says Eric Rath, a professor of Japanese history at the University of Kansas, who recently published a paper on narezushi. “The rice is like paste and overcooked. It’s the most sour part.”

Though narezushi is an acquired taste, it’s one that’s been popular across Asia for millennia. According to Yoko Isassi, an L.A.-based Japanese cooking instructor, this form of sushi can be traced back to ancient southeast Asia, between the 3rd and 5th-century BC. Indeed, there are narezushi-like dishes all throughout southeast Asia and southern China, exclusively in places where rice is a staple crop. In the Chinese province of Hunan, there’s yuzha, where carp is fermented with black rice, chili powder, and salt. In the Philippines, there is burong isda, fish cured with salt, red yeast rice, and cooked rice. And in Thailand, there’s pla ra, river fish preserved with rice bran and salt. They all look and taste quite similar: soft, rotten fish covered with liquified rice. These commonalities suggest that these dishes are all somehow related.

But Rath notes that saying that sushi originated in southeast Asia is an oversimplification, because there’s no evidence. “We don’t know where it comes from. People say southeast Asia solely based on ethnographic research,” he says.

Today in Japan, narezushi is very much a regional specialty. It’s most famous in the Shiga Prefecture, just northeast of Kyoto and in the areas surrounding Lake Biwa. Lake Biwa, Japan’s largest freshwater lake, is flush with carp, and the narezushi sushi made from there is called funazushi.

“Up until medieval times, people made sushi with fresh fish from the lake,” explains Rath, who spent several days in the Lake Biwa region sampling funazushi variations for his research. It was only when the capital of Japan moved from Kyoto to Tokyo that making sushi with ocean fish became the norm, he says. Tokyo—unlike Kyoto—has easy access to the sea.

“Funazushi is made with crucian carp,” says Rath. “It’s a very small fish closely related to the goldfish and there are different varieties.” Crucian carp are usually caught in spring, when the females are full with eggs, and then salted for a minimum of six months.

Because the fermentation time for funazushi is so long—sometimes up to several years—the rice fermented with the fish becomes so decomposed that it’s often considered inedible. It’s usually scraped off and discarded, leaving the fermented fish and roe. The taste of mature funazushi is pungent and sour, with an occasional sake-like aftertaste. Because of the time needed to ferment, it’s usually only brought out for holidays and special occasions to be sliced and eaten atop rice. “It’s really a delicacy,” stresses Isassi.

Though Toho Chaya is best known for their older offerings, such as the 30-year-old narezushi, the majority of Matsubara’s fish isn’t pickled for nearly as long. “We cut and open the fish, gut it, remove the bones and then pickle them with salt for ten days to a month,” says Matsubara. “Then after that, we scrape the salt off and stuff them with the steamed sticky rice. We use a wooden barrel with fern leaves at the base of it, pack in dozens of rice-stuffed fish, and then cover with the fern leaves on top. These fish are weighed down with a heavy stone and pickled for three weeks to a month. After that, we flip the barrel over and put the stone on it to drain out the water.” This narezushi technique, introduced somewhere around the 14th century, is considered more modern than the technique used to make funazushi, and takes much less time.

Today, sushi has come a long way from the narezushi days, mostly due to societal changes in Japan. In the 19th century, explosive economic growth and a busy working class led to the genesis of modern sushi culture. It was during this period that sushi became a fast food, with vendors packing pre-cured fish on top of vinegar-seasoned rice and selling it on the street. “People started learning about seasoning instead of just waiting for a long time,” says Isassi. “They started seasoning the rice separately with vinegar and sugar.” Vinegar, she says, is great at mimicking the acidic bite of naturally lactic acid-fermented rice.

As time went on, the curing time of sushi fish was eventually shortened from several weeks to a couple of hours. Refrigeration has since completely eliminated the need for a curing process, and most sushi sold today is simply raw fish over lightly seasoned rice. It’s almost the antithesis of its original form—ocean fish instead of river fish, fresh ingredients instead of aged, and a dish that’s assembled quickly instead of very slowly. But while narezushi may have waned in popularity over the centuries, it’s still very much a classic, passed down the generations under the careful care of chefs like Matsubara of Toho Chaya.

“I’ve been watching my grandparents and parents make narezushi since I was a child,” he says. “The taste of narezushi changes a lot depending on the amount of salt and temperature. I’ve tried countless times and made numerous mistakes.” The key to perfect, pungent narezushi, declares Matsubara, is always to rely on the senses, “not on the brain.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook