7 Hours in the Air With Some Record-Breaking Swiss Balloonists

Up, up, and away over the Alps.

When we entered the clouds I started to question the decisions that led me to dangle in a wicker basket 8,000 feet above sea level with nothing between me and the alpine chop but a bit of plywood, straw, and air.

The four of us in the balloon basket had launched predawn from a small airfield in the Swiss city of Villeneuve, on the edge of Lac Leman opposite Geneva. We’d risen over the lake and through a saddle between the low mountains that hemmed the water, then swept over the Pays d’Enhaut and through the Simmen Valley.* At times, our balloon floated so close to the hillsides that I could smell their dank, loamy scent. Then we rose over the Alps and drifted northeast towards Thun. Our speedometer clocked us at 30 mph, but because we travelled at the same speed as the wind, I did not feel our pace at all. The stillness was eerie and stunning, interrupted only by the periodic roar and hiss of the propane burner.

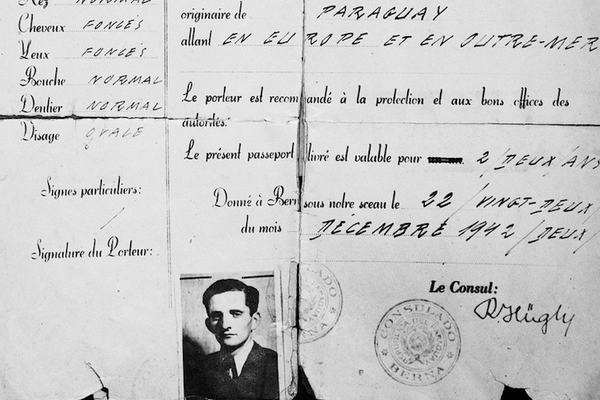

I was relaxed only because I knew I was flying with the best. Two of my companions, Laurent Sciboz and Yannick Serex, were members of the Swiss team that holds the world record for the longest, continuous hydrogen balloon flight. They shattered the standing record when winning the 2017 America’s Challenge Gas Balloon Race. Sciboz was half of the two-man crew in the balloon. His team, the Fribourg-Freiburg Challenge, launched from Albuquerque, New Mexico and landed outside of Labrador City, Newfoundland, 59 hours, 19 minutes and 2,280 miles later. As part of the team’s ground crew, Serex followed the balloon’s path in a van, keeping them aloft through the tail end of a hurricane that swept the balloon over America at 88 mph.

Keeping two men in the air in a basket the size of half a bathtub for seven days requires physics and psychology, Serex told me as we floated over Lake Gruyere. “But then,” said Yannick with a grin. “I’m not a psychologist!”

I met Serex near his home in a small Swiss mountain town nestled in the Jura mountains, about an hour and half from Geneva by train. By trade, he works as an electrician, heating specialist, fumigator, and plumber. But when he handed me his business card, it read Yannick Serex, Aérotisier—French for “balloonist.” He’d invited me for what I’d presumed would be a short, touristy balloon trip. We’d gathered up the two other pilots, Laurent (who works as a programmer) and a former student of Yannick’s, Louisa Felis. At 28, Felis is a licensed and highly competitive ballooning pilot in a male-dominated sport. Of all of us in the basket, she’s the only one who owns her own balloon. When not in the air she works as a truck driver, horse-trainer, and mortician.

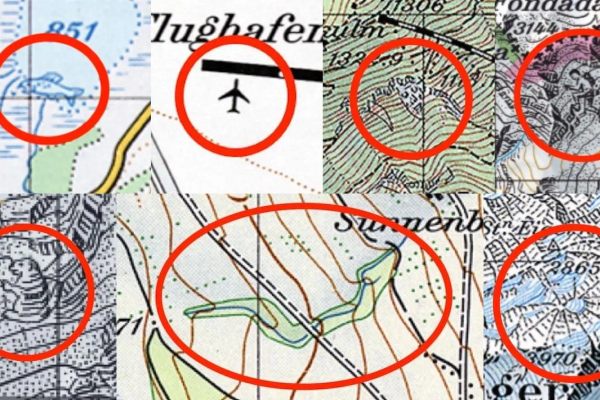

As we drift over the peaked red roofs of the oldest monastery in Switzerland, Sciboz and Serex told me: The America’s Challenge is an endurance race. There are few rules and no finish line. Victory is not about who arrives at a location first or even who stays in the sky longest. It’s about who travels the greatest distance. The trick is always to find fast wind without bad weather. But that’s easier said than done. In a balloon you have no control over the direction, only your altitude. In a gas balloon, the adjustment of altitude requires heat, or the release of hot air. In a hydrogen balloon, like the Fribourg-Freiburg Challenge, the envelope is filled with a fixed amount of gas at the start and weighted down by sand. To control altitude or the pressure of the balloon, you release gas or, more often, dump sand. Without burners, travel by hydrogen balloon is silent.

In all the films of Sciboz’s trip the shadow of the balloon sweeps over the landscape to the sound of his breath. It’s the only sound. For seven days, Sciboz and his co-pilot slept in shifts on a bed created by lowering a trap door in the side of the balloon, through which the sleeper would stick his feet and legs. A lined bucket for a toilet. A single seat. Through scalding sun, then rain, then snow. This, in an ecosystem so finely balanced that the evaporation of the crew’s sweat lightened the basket enough to rise. It’s not a sport for the aggressive or the impatient, rather it rewards a certain kind of sensitivity to the call-and-response of the world and a delight of travelling without control over your destination. You drift and land where the wind and the balloon decide.

The Fribourg-Freiburg Challenge crew landed in the snow-strewn scrub of a bald patch of Newfoundland forest so remote that they had to be retrieved by helicopter. When the nearest police chief was alerted to their presence, he thought it was a joke. The second-place team, from Poland, clocked 69 hours and 4 minutes, but fell short of the distance of the Swiss Team by 89 miles. In their final hours, the Polish crew threw much of their equipment, their sitting bench, and their personal gear over the side of the basket to try to lighten their balloon enough to cross the St. Lawrence River.

“Flying the balloon is like life, the destination is always unknown,” Sciboz told me, while Serex hooked me up to an oxygen tank so that I could breathe as we ascended above 7,000 feet. Once removed from earth and gliding over it, our world feels peaceful. Manageable, even.

We’d risen out of the valley, left the miniature cows and trees and patchwork pastures behind, and reached the level of the snow-capped Alpine peaks. I was bundled in a red snowsuit. The temperature dropped to 14℉. The Alps spread out before us like jagged white-capped waves. Suddenly the sea of mountains was enveloped by clouds. The grey wall so thick, I believed I could reach out and grab handfuls of cottony matter. My oxygen monitor beeped, my feet had grown cold, but the giant flame that heated the balloon at intervals warmed my face and neck. The acrid scent of propane lingered after each burn. We kept rising over the dazzling cloudscape of sun and azure sky and glittering mountaintops to 14,763 feet.

We landed in a field outside a small village called Kaufdorf, having travelled 42.2 miles overland. There is no runway, no airfield, no wind sock or signposts. Our basket bounced on the ground once, then tipped about 15 degrees off center. In fierce wind, the snag is sometimes hard enough that the crew is thrown. The balloon deflated and collapsed into the grass, and we became earthlings once more.

It had been hours since I ate or drank or had proper rest, but I wanted for nothing. By hovering above the world, I’d found more intimacy with it. Serex said the feeling is the same whether racing or executing an arduous trip over the Alps: “In the air you detach. But when I fly at night and look down at the lights, I wonder who sleeps? Who wakes? You look down and you see the stories—the stories of the lives of others. You can descend into them. It’s not far … therefore you hold riches.”

This strange feeling of lightness and wonder stayed with me long after we dismantled the balloon. If you are desirous of a shift in perspective, rather than focusing on speed and destination, I recommend the balloonist’s solution: travel where the wind decides.

*Correction: The story originally referred to the Intyamon Valley when it meant to specify the Simmen Valley.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook