How a Midwestern Potato Farm Became the World’s First Nuclear Waste Site

One company in St. Louis produced nearly all the uranium used in the Manhattan Project.

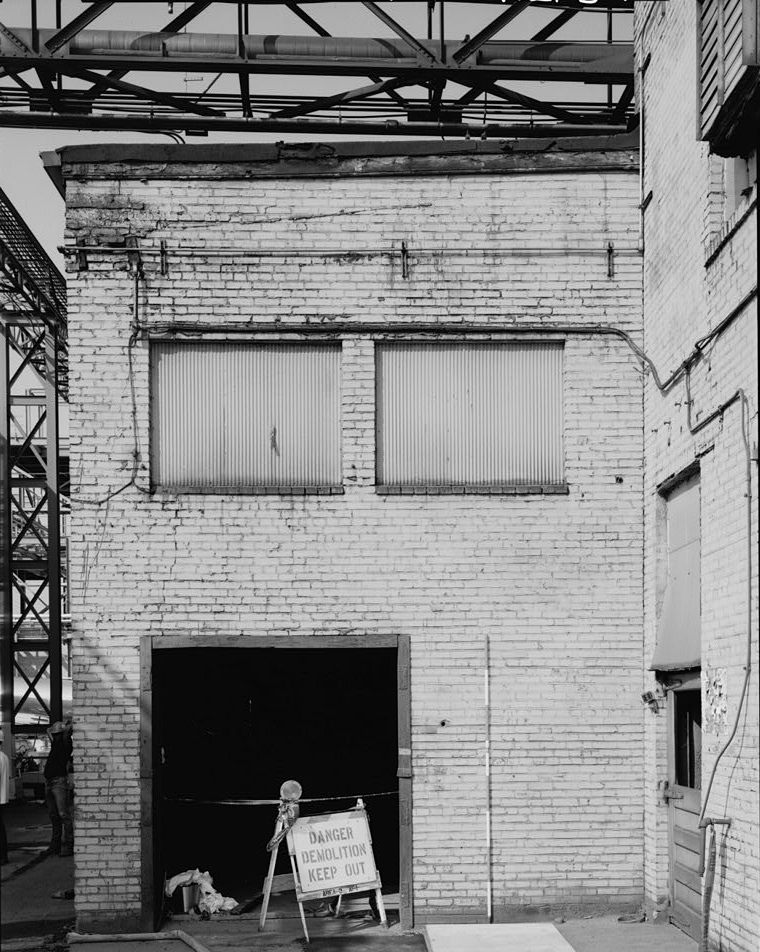

The interior of Building 51 of the Mallinckrodt plant, where uranium was processed. The building was demolished in 1996 as part of the Department of Energy’s remediation effort. (Photo: Library of Congress/HABS MO-96-SALU,134B–5)

It’s abundantly clear from their 1962 newsletter that the employees of the Mallinckrodt Chemical Company’s Uranium Division were proud of their work. On the division’s 20th anniversary, they produced a cheerful tribute to “growth and progress in research, in management, in human relations–and in the total reputation of the organization.”

The newsletter circulated through office mailboxes and break-rooms in a bustling, cutting-edge facility on the suburban fringes of St. Louis, Missouri. Today the spot is covered by a 45-acre, 75 foot-high waste-disposal cell, entombed under layers of clay, sand, and gravel.

During the anniversary celebrations of 1962, everyone from executives and inventors to guards and porters got a share of credit for the company’s achievements, such as producing almost all of the uranium used in the top-secret Manhattan Project. During War World II, workers logged 14-hour days, seven days a week. But until the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, most Mallinckrodt employees didn’t know what uranium was or what it was for. Nonetheless, they were gratified to be such a crucial part of the war effort.

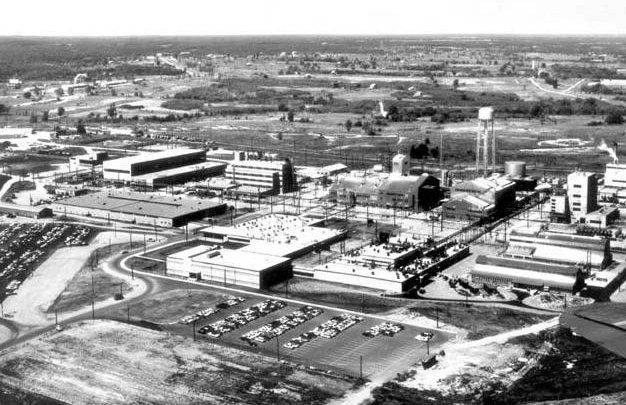

An aerial view of the Weldon Spring site. (Photo: Public Domain)

The environment they worked in back then would never pass muster in today’s top-secret facilities, where Hazmat suits are commonplace. In the newsletter, company veterans recalled the “crowded, almost primitive conditions in the early days of the project,” when it was housed in a former stove factory in downtown St. Louis. These conditions included frequent explosions, clouds of uranium dust, and leaking chemical drums.

The spark that transformed Mallinckrodt from a manufacturer of medical and photo developing chemicals to an engine of nuclear armament occurred in 1942, with the arrival of “important visitors” from Chicago, who had an unusual request.

In 1941, scientists at the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory had decided to attempt a nuclear chain reaction, in which the neutrons freed by splitting a radioactive isotope collide with and split more atoms, whose neutrons in turn split other atoms, releasing vast amounts of energy. They feared that German physicists could master this reaction and harness atomic power to win World War II. However, a chain reaction required precisely-controlled conditions–what the physicists termed “critical mass”–and tons of extremely rare purified uranium.

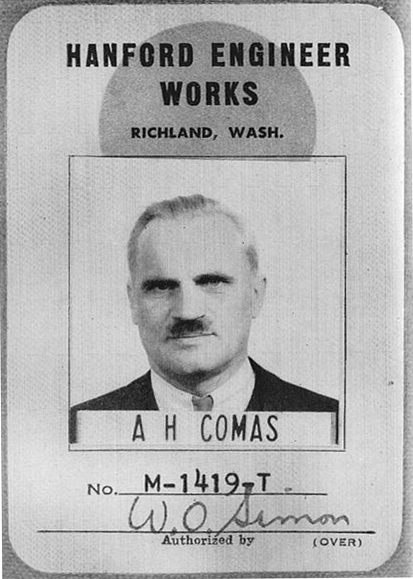

Physicist Arthur Compton’s ID badge from the Manhattan Project’s Hanford Site. For security reasons, he used a fake name. (Photo: Public Domain)

Physicist Arthur Compton’s ID badge from the Manhattan Project’s Hanford Site. For security reasons, he used a fake name. (Photo: Public Domain)

In the Metallurgical Laboratory, scientists had obtained small amounts of fissile uranium with a technique called ether extraction: when crude uranyl nitrate was combined with volatile liquid ether, its impurities separated out. About half a cup of this purified uranium existed in the United States in 1941; to attempt a chain reaction, researchers needed 45 tons.

Three other companies had already refused the Chicago laboratory’s plea for uranium due to the expense and danger of producing it on such a massive scale. On that afternoon in 1942, Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr., the president of Mallinckrodt Chemical Co., listened to their proposal, shook some hands, and announced to his employees that they’d joined “a secret project of great importance to the war effort.”

The next day, designers descended on Mallinckrodt’s Buildings 50, 51, and 52. Dispensing with blueprints, they sketched on floors and walls with builders following hot on their heels. “All available company personnel who could contribute in any way were commandeered,” recalled lead engineer John Ruhoff. In less than three months, the Division was turning out 30 tons of purified uranium per day.

A 1921 advertisement touted the purity and reliability of the ether anesthesia made by Mallinckrodt. (Photo: Public Domain)

The medical substances in Mallinckrodt’s manufacturing repertoire made the pivot to uranium purification easier than it would have been anywhere else. Established by three German-immigrant brothers on their family’s potato farm in 1867, the company had long produced drugs that were ubiquitous on pharmacy shelves. Its first venture into radioactivity was for medical purposes. In 1913, its chemists developed barium sulfate as a contrast media for emerging x-ray technology. Mallinckrodt also happened to be a reliable producer of ether, widely used as an anesthetic. Perhaps this special combination of circumstances gave Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. confidence that he could deliver what Arthur Holly Compton, of the University of Chicago’s Physics Department, later called “a technological and industrial miracle.”

A former manager recalled that “the word [radiation] had little meaning” in those early years, citing a worker who supposedly remarked “I don’t know what the stuff is but they tell me it’s radioactive–so it must be for radios.” Secretary Jeanelle Hoffert wrote that “workmen supplied their own clothing and tools; health regulations as we know them today were almost nonexistent.” Their casual attitude sounds naive to modern ears, but at the time radiation was an alien danger, invisible, slow-acting, and lifelong.

Mallinckrodt’s employees were well aware of the faster-acting health risks inherent in chemical work. They were surrounded by noxious acids and volatile ether; accidents happened frequently, and workers like foreman Carl Feisel took pride in understanding their materials and knowing how to respond. Speaking to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1988, Feisel described safe chemical handling as a kind of craft knowledge, passed down among generations of workers who understood the need to protect themselves and each other.

Building 51 after it had been marked for demolition. (Photo: Library of Congress/HABS MO-96-SALU,134B)

Of course, management, scientists, and the government knew that radiation had damaging long-term effects and that workers were at risk. Indeed, St. Louis became the proving ground for the first standardized safety measures. Mallinckrodt’s president implemented a badge system in 1945 to keep track of exposure, although no one knew where to set the limit. In 1947, after workers had been handling uranium for five years, the company hired engineer Mont Mason to teach about radiation safety. It was an uphill battle. “We were just back from the war… and Mason and these guys were talking about protons and neutrons,” one worker told the Post-Dispatch. “Half of the men slept through the lectures.”

Mason recalled “starting from scratch. I had to build my own instruments to measure the radiation.” When the AEC established exposure limits in 1950, 36 employees were transferred out of the Uranium Division immediately, thanks to the record logged on their badges.

Due in part to pressure from Mason, who became a tireless advocate for worker safety, the AEC would spend $300,000 on safety measures at Mallinckrodt. But by 1957, there was simply no way to manage the contamination and health risks in the company’s 19th-century buildings. The Uranium Division abandoned its downtown plant, leaving behind radioactivity that still shows up in aerial surveys despite ongoing attempts at remediation.

An aerial view of the Weldon Spring Chemical Plant, Missouri, which was operated by Mallinckrodt from 1957 to 1966. (Photo: Public Domain)

The Division migrated to a spacious new complex in Weldon Springs, Missouri, built by the Atomic Energy Commission to beef up the nation’s Cold War infrastructure. Employees called it “The Clean One”: a quarter of the construction budget was devoted to automation and worker-protection measures. For a decade, this new location cranked out uranium at three times its intended capacity, never missing a quota–until, abruptly, it wasn’t producing anything at all.

In 1967, the Atomic Energy Commission placed Weldon Springs on indefinite standby. They switched their uranium production to a plant in Ohio; some speculated that inter-state political wrangling in Congress triggered the move. As happened with many military suppliers after wartime, Mallinckrodt was left with a plant for making material that no one besides the AEC needed. The city of St. Louis and adjacent St. Charles County were left with millions of cubic yards of radioactive waste.

Responsibility for the waste bounced around among the Department of Energy, Army Corps of Engineers, and Environmental Protection Agency; promised multi-million-dollar cleanups at the downtown and Weldon Springs sites dragged out for decades, while contaminated dirt and groundwater spread through the region without the knowledge of residents. The Post-Dispatch talked to people who recalled digging in orange, uranium-tainted mud as children, thinking they’d struck gold. After a process more complex and toxic than anyone had anticipated, the Weldon Springs remediation was declared complete in 2001.

It’s possible to climb the waste site for a view of the countryside. (Photo: Public Domain)

A nature preserve and interpretive center surround the towering pyramid of nuclear waste, which visitors can climb for a view of the surrounding countryside. On this site in 1962, Uranium Division workers flipped open a special edition of their company newsletter emblazoned with the slogan, “What is past is prologue.”

Intended to celebrate the ongoing “effectiveness of health measures and the good name of Mallinckrodt as an industrial neighbor,” the slogan only looks ominous from the vantage of the present day. In and around St. Louis, the radioactive past is still very much alive.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook