How Meat Science (And Marketing) Gave the World the Flat Iron Steak

It was only recently popularized.

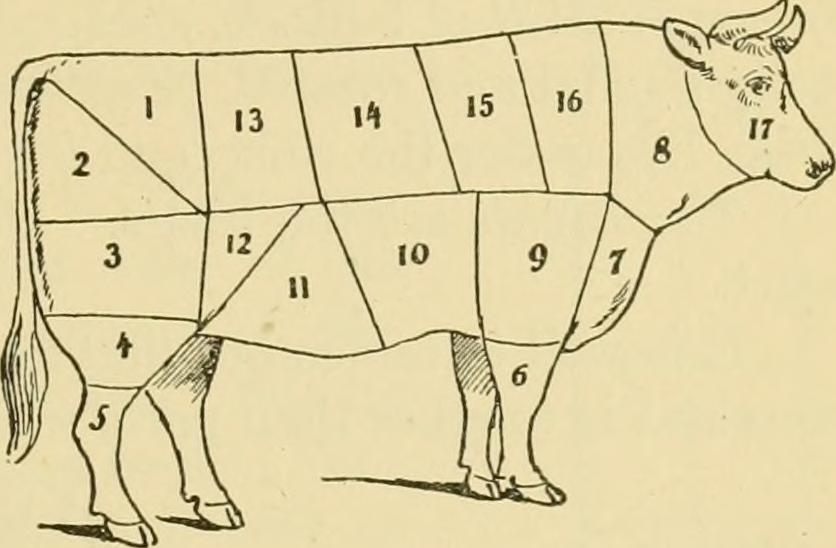

Scientists have been involved in the discovery of some cuts of beef, such as flat iron steak. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

You may not like meat, but even if you do, you may not think of it in terms of innovation.

It sounds like a concept incompatible with the idea of meat—we do so many things with cows, chicken, fish, and pigs that it’s difficult to consider these animals in terms of reinvention. We’ve already mashed these four types of animals into combinations more creative than Legos, taken their parts and turned them into products that don’t even fit into the same genre as dinner.

But there is in fact still innovation is to be had at the dinner table. And it’s all thanks to the same federal programs that allow different kinds of animal byproducts to advertise themselves on television.

And it’s particularly been successful in the case of beef since the passage of the Beef Promotion and Research Act, a 1985 law that requires that a dollar be collected for each head of cattle sold. (Organic beef, however, is generally exempt from this per-head rule.)

Essentially, it’s a tax on beef production, but the tax goes directly back to the beef industry. Specifically, it goes toward all those “Beef: It’s What’s for Dinner” commercials, along with investments in research and development.

And it’s that research and development that has been giving meat science a kick in the pants over the past 20 years.

The beef checkoff program doesn’t just exist to tell you how awesome beef is.

It also has an important role in improving the value of beef as an investment. Let me explain: Basically, a cow has a set price, a specific value, and that value is set by the market. (Don’t believe me? Check the market data.)

If too many cows are on the market, the value of a cow drops. If too few, there’s a shortage and the price of a steak at the supermarket might go up. And some types of cows are more expensive than others. You know, basic economics.

At the same time, some parts of the cow are more valuable than others. Tenderloin, for example, tends to be more expensive than chuck. Certain sections of the cow get a prime spot in the meat section; other parts get ground up and spread about every other part of the grocery store.

Flat iron steak. (Photo: Jun Seita/CC BY 2.0)

But there’s always room to make a cow more valuable, and that’s where the work of Chris Calkins and Dwain Johnson comes into play. Calkins is a meat scientist at the University of Nebraska, while Johnson plays a similar role at the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Together, these men had a great idea: Let’s research the muscle structure of your average cow, focusing on the cheaper cuts, and seeing if there might be some hidden value in there.

The duo, with the help of the National Cattleman’s Beef Association, researched new cuts of meat from parts of the animal that would have otherwise been turned into hamburger. In the largest study of its kind in 2000, the scientists tested 5,600 muscles for flavor and tenderness. They found 39 worth their time.

Sounds like a weirdly specific line of work. Guessed who helped fund that research? That’s right, the beef checkoff program, which quickly saw dividends from this work.

In 2002, these guys hit the jackpot: They uncovered an impressive new cut of meat called a flat iron steak, trimmed from the shoulder area of the cow, a place more traditionally associated with cheaper chuck beef that’s ground into burger.

Essentially, the researchers discovered that if the connective tissue of the cow was trimmed off in a certain way (as shown in this clip), the cut left behind was flavorful and punched above its weight class compared to more costly types of steak.

“Supposedly named because it looks like an old-fashioned metal flat iron, the flat iron steak is uniform in thickness and rectangular in shape,” Johnson said in a 2007 press release about the research. “The only variation is the cut into the middle where the connective tissue has been removed.”

That cut quickly became hugely popular with the public, thanks to the fact that it was cheap, but still very high in quality. High-end restaurants that would have skipped chuck in building their steaks put the flat iron steak on their menus.

A report from Beef U, an education offering provided to the food service industry via the beef checkoff program, highlights the benefits of this kind of research throughout the system:

Turning the underutilized chuck and round into these new cuts means more profitability and higher margins for foodservice operators. In addition, while these cuts have a significant impact year-round, foodservice operators can leverage key benefits during certain times of year. For instance, when both demand and price for steaks increase during summer months, operators can feature more steak options, increasing traffic and margins.

By 2012, according to the Meat Institute, the flat iron steak was responsible for around $80 million in sales.

Clearly, there’s something to be said for meat science—or at least for clever naming strategies.

Since the flat iron steak took hold, the meat industry has been on the lookout for new cuts of meat that could prove just as buzzy for the public.

In recent years, more cuts of meat have tried to follow the flat iron’s carefully-cut path from the butcher to the grocery aisle.

Among the more notable ones:

Denver Cut Steak: This variety, found in the same bout of research as the flat iron steak, was first introduced to the public in 2009, and also comes from the chuck area. The steak, despite being seen as intensely flavorful, has struggled to have the impact of its more famous cousin, according to Denver’s alt-weekly, Westword, which wrote a lengthy feature last year about the steak cut named after its city.

Vegas Strip Steak: Business consultant Tony Mata (who worked closely with researchers on the flat iron steak project) worked with researchers at Oklahoma State University to come up with yet another kind of meat from the chuck area—one that requires a non-standard butchering strategy. But what’s most surprising about the cut is how it’s being sold: Mata and the researchers patented the cut and are trying to license it out.

The beef section of a supermarket. (Photo: Anthony Albright/CC BY-SA 2.0)

And these new kinds of cuts, controversial as they may or may not be, are still being invented to this day. Even the National Pork Board is getting in on the name game, teaming with the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association to research naming conventions for cuts of meat.

The two groups found that more common pork cuts were considered confusingly named, so in 2013, the pork board announced a new strategy: It decided to rename its cuts in a style closer to beef. So as a result, a loin chop is now a “Pork Porterhouse Chop” and a rib chop is a “Pork Ribeye Chop.”

“The new names will help change the way consumers and retailers talk about pork. But more importantly, the simpler names will help clear up confusion that consumers currently experience at the meat case, helping to move more pork in the long-term,” explained the pork board’s president, Conley Nelson, in a press release.

Meanwhile, meat scientists are still out there, finding new cuts of beef. Back in August, the University of Nevada, Reno revealed that one of its on-campus meat scientists, Amilton de Mello, found yet another new cut near the chuck area—one he’s calling the “Bonanza Cut.”

De Mello, who came to the university last December, says that the cut is actually near where the flat iron steak is.

“When you separate the chuck and the ribs, the Flat Iron steak goes one way—with the Chuck—and the relatively small end stays with the rib side; this is the Bonanza Cut,” de Mello told Nevada Today, a publication of the university.

A big part of the reason de Mello spotted it was some good perception. According to the Las Vegas Review-Journal, he spotted the piece of meat while working at a beef-processing plant, thought it to be well-marbled, and decided to test it out.

Flat iron steak was discovered by scientists, who researched the cuts that would normally end up in hamburger. (Photo: stu_spivack/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The high-quality cut of beef is tiny—the two four-ounce pieces in each cow may struggle to fill you up on their own—but the high fat content (estimated to be 13 percent) gives the cut a richness that, if sold properly, could prove extremely valuable for the beef industry.

And the cut has a fan who knows a thing or two about discovering new cuts of meat: Chris Calkins, the University of Nebraska professor who helped discover the flat iron steak.

“Upgrading this meat from a ground beef/trim price to steak-quality price should return more dollars to the industry,” Calkins said, according to Nevada Today. “I anticipate a positive reception for the Bonanza Cut, especially from countries that recognize U.S. beef for its quality and flavor.”

Spoken like a guy who knows his steaks.

The production and discovery of new cuts of meat comes at a time when unusual cuts are starting to be seen as, well, kind of hip.

Unusual cuts have a significant advantage for some restaurants, which can use these cuts to lower the price range for higher qualities of meat (think kobe beef) to something approachable for more types of consumers.

Manhattan’s Quality Eats restaurant has been taking advantage of this market dichotomy. Michael Stillman, the owner and founder of both Quality Eats and parent firm Fourth Wall Restaurants, sees this as a big advantage for consumers.

“I don’t think it’s unconventional as much it is expanding on convention,” Stillman explained to Zagat. “Diners have a growing interest in sustainable eating and the nose-to-tail cooking movement has opened minds to new options.”

Trendy or not, weirdly placed or not, these animals have been feeding humans for ages. Are we learning new ways to produce and eat them, or are we just getting better at marketing? Or is it both?

A close-up of a porterhouse steak. (Photo: Naotake Murayama/CC BY 2.0)

In a lot of ways, animals in this raw-meat form are like putty, with the value of their many parts arbitrary. We only think filet mignon is the best cut of meat because that’s what we’ve been told as a society, and decided it’s worth our money for reasons less scientific and more a matter of preference. The new-cut strategy exploits those preferences and tries to find them in as many places as possible.

On the other hand, the reason why researchers have discovered these new cuts of meat is still worth pondering. It’s evidence that, if we look hard enough at something and consider moving past the limitations we’ve created for that product, there’s a chance we’ll find something new, something that adds value.

You may not care about the difference between a Porterhouse steak and a Vegas strip. Despite the fact I wrote this, I certainly don’t. But if there’s an issue in your way, a frustration you’re trying to get past, it always helps to have a fresh set of eyes, a willingness to try a new tactic, and a little bit of ambition to move forward even if people think your idea is a little crazy.

I know, that’s a surprisingly deep point to take from a bunch of scientists cutting meat in clever ways, but hey—it’s a meaty subject.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook