Notes From The Field: In Search of the Green Fairy in New Orleans

“The Absinthe Drinker” by Viktor Oliva (1861–1928)

One of the most important things to us here at the Atlas is to always keep traveling and discovering. Notes from the Field are first person reports from trips taken by the Atlas Obscura Team.

I had no illusions. Walking down raucous Bourbon Street on a hot night in New Orleans, I was not expecting enlightenment. Though the 24-hour party atmosphere makes the street an iconic destination for revelry, it is decidedly not where one finds deep and bohemian illumination.

Still, as I pushed past bachelor parties and sunburnt tourists adorned with plastic beads, I had a singular destination in mind. I was in search of The Green Fairy. And I had it on good authority that I could find her at Jean Lafitte’s Old Absinthe House, where I would have my first taste of absinthe.

Absinthe, of course, is the legendary green liquor once adored by artists and writers. Its alleged hallucinogenic effects (thujone was present in the drink as a result of producers commonly using wormwood as an ingredient) led to a serious mystique surrounding the liquor, and its nickname “The Green Fairy” was spawned as a euphemism for the supposedly unique effects of being drunk on the stuff.

But the “bonus” intoxication from absinthe made it more than just a poster child for the bohemian and artistic crowds. The drink was also vilified in the temperance movement’s claims about the danger and immorality of alcohol. When a Swiss farmer named Jean Lanfray murdered his family while drunk on absinthe (and a number of other things), a worldwide backlash uncoiled, resulting in a near-global ban that lasted for most of the 20th century. In the United States, the ban lasted until 2007.

Albert Maignan, “La Muse verte” (1895)

Naturally, the resulting “forbidden fruit” taboo is intoxicating in itself. It’s the reason I found myself mired in a bacchanalian sea of tourists in America’s most liminal city. New Orleans straddles the line between old-world charm and postmodern irreverence—where plastic banners announcing drink specials lie draped across antique wrought iron balconies. Looking out at college students shuffling down the cobblestone streets in rubber sandals, you can’t help but notice how the city is so bemusedly stuck between two worlds.

Gone are the days when ladies of the night leaned out of second-floor windows in Storyville with their silk fans, or arched their legs out of darkened doorways to entice passers-by into the brothels. But not as gone as you might think. Much of the city has been commoditized, but in certain quiet corners, the old world lingers.

Photograph from Storyville by E. J. Bellocq (1873 – 1949)

That’s what makes New Orleans the perfect place for absinthe, itself the Rip Van Winkle (with due respect to the bourbon of the same name) of spirits, having disappeared for a century only to reappear in a world wholly different from the one it left.

The roots of French influence stretch deep into the core of New Orleans, but the city’s special relationship with absinthe goes beyond ancestral homage. Turn-of-the-century New Orleans was known for its appeal to artists, writers, and other bohemian types, even more than it is today—and they wanted their drink.

On nearby Royal Street, yellowed propaganda posters and antique drinking sets sit proudly along the walls of the Absinthe Museum—an engrossing collection of pre- and post-Prohibition Era artifacts and history, most of which focuses on the drink’s relationship to historic New Orleans.

The Absinthe Museum (via)

But to truly understand that relationship, you have to make your way to the corner of Bourbon and Bienville streets, where I found myself, in front of the Old Absinthe House.

The building stands apart from the rest of Bourbon Street—literally. It’s one of the few freestanding buildings in the French Quarter, silently attesting to the location’s historic importance.

Old Absinthe House (via)

The whitewashed facade is broader than other, typically narrow, Bourbon Street establishments. It was obviously constructed at a time when squeezing more and more real estate into finite square footage was not a priority. And its traditionally ornate balconies are higher than the others in the Quarter—too high for tossing beads.

I had my doubts about the bar. I had already passed any number of neon-lit corridors of barstools overflowing with tourists and throbbing dance music on my way to it, and I wasn’t sure how “historic” the place would be. But once you spot it, the crowds seem to blur around you. Your vision dims a bit at the periphery. It stands alone.

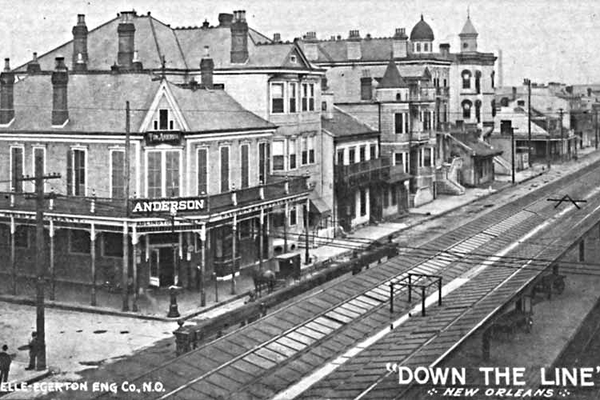

Old Absinthe House in the 1890s (via Louisiana Photograph Collection)

When I stepped through the doorless entryway, the feeling only intensified. The room was dark, its cracked walls painted black. The thumping dance music of Bourbon Street was replaced by a vaguely audible growl of rock music vibrating from a jukebox in the corner. The uncrowded room smelled like smoke and sweat and brick.

The star of the tavern is its massive bar, which is over 100 years old and decorated with ornate designs inlaid into its solid oak. It fills most of the tavern’s single open room, with just enough space around the sides for separate tables.

I took a seat at a table in the corner, not wanting to approach the iconic bar quite yet. In the next room of the same building is a restaurant, and the windows between the two halves are so old the glass has warped into frozen ripples. From my perch I could see the distorted figures of couples dining next door.

I looked at the bar. 90 years ago, an angry mob showed up at the Old Absinthe House with a mission to destroy it. Prohibition had gone into effect, and the tavern was shut down. But its legend lived on. Historic figures like Mark Twain and Oscar Wilde whiled away hours at that bar, and destroying such a piece of history would have been a symbolic act, heralding the death of recreational drinking in America.

Old Absinthe House in 1903 (via)

But when the mob arrived, they found the building empty. Anti-prohibitionists and supporters of the tavern had moved it in the night, stashing it in a warehouse for safekeeping. And there it sat, even after Prohibition ended, until the bar reopened decades later.

As I absorbed all of this, my romanticism began to fade a bit. It was an historic building, but parts were just as conflicted as Bourbon Street outside. Football memorabilia hung from the ceiling for no discernable reason. Patrons around me drank from plastic cups.

I approached the bar, and I was greeted by a cheerful bartender in a corset, and trust me when I write that it was not the Victorian sort. Her name was Maria, she had worked there for three years, she was from Florida, and when I ordered an absinthe, she asked what kind.

“The real one,” I heard myself reply, hoping she knew what I meant. I know I didn’t.

Done correctly, drinking absinthe is an elaborate process, and a remarkable feat considering how busy the poor bartenders are at the Old Absinthe House.

Maria dutifully poured the cloudy green liquor into a glass—a glass glass—and then balanced a slotted spoon on top of it. She placed a cube of sugar on the spoon before moving the whole set beneath a tiny marble water fountain built directly into the bar.

Old Absinthe House fountain (via)

The marble fountains are original, and by far the most iconic part of the entire tavern. Here is where ice water dripped over sugar cubes and into the glasses of Wilde and Twain and General Robert E. Lee, and where it would flow into mine, creating a perfect, traditional, absinthe.

After the sugar dissolved completely, Maria stirred the glass and handed it to me. I graciously thanked her, then felt a slight unease. For me, the fun part was over—the most historic and romantic aspect of the experience had now passed, and all that was left was the drinking.

I raised the glass to my lips. It was bitter, strong, and captivating. I hate licorice. Maria smiled. I took my time with it, wondering, just a little bit, if I would feel something extra—something beyond the alcohol. A visit by The Green Fairy.

Outside the open-air doorframes, a wedding parade passed by: trumpets blaring; drums thumping; people dancing. Beyond that, neon beer signs sliced through the tawny glow of the old gaslight-inspired streetlamps. And somewhere nearby, Lake Pontchartrain lapped at the coastline—a swirling, murky mixture of fresh and saltwater that provides the city’s fisherman with the work they, and the city, need to survive.

With the last, sugary sip of the green tonic, it got a little harder to tell exactly where I was. Outside, the plastic shrank. The neon faded. Again, the room was dark and smelled like sweat and smoke and brick.

I ordered another.

FIND THE GREEN FAIRY YOURSELF:

JEAN LAFITTE’S OLD ABSINTHE HOUSE, New Orleans, Louisiana

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook