Indigent Burial in the U.S. is Shrouded in Confusion and Inconsistency—But There is Hope

(Photo: PhotographyByMK/shutterstock.com)

On July 19, Rosaria Cortes Lusero was able for the first time to visit her stillborn daughter’s burial site. She had died just a few days after being born in 1995 and—as is the case with all stillborn infants where no private arrangements are made—buried in a mass grave site on Hart Island in the Bronx which the public could not access.

Lusero was the lead plaintiff in a class action lawsuit brought by the New York Civil Liberties Union against the city on behalf of families that wanted regular access to the site. In a settlement agreement, family members and their guests would be allowed to visit grave sites once a month. The legal justification for these restrictions put forth by New York City is that handling of indigent burials is done by its Department of Correction, the same agency that manages its prison. The department would cite safety concerns due to the island’s lack of public facilities and its open burial pits. This also led to complaints by visitors that they were being treated more like prisoners than mourners.

While Hart Island is certainly unusual, it’s by no means unique. Across the country, counties manage their processes with complete inconsistency. In some places it is administered at the state level while in others it is left up to individual counties. Some locales will cremate while others will bury. In an ideal world, the dead would not be left unattended in the care of cash strapped bureaucracies, but they often are. Years of pressure by New York City residents was instrumental in bringing about increased transparency at Hart Island.

After decades of neglect, it seems that the public might be demanding answers about how local governments act as undertakers of last resort.

Hart Island was purchased by New York City in 1868 for use as a potter’s field, a place to bury those that couldn’t be identified or that were too poor to make their own arrangements. It is about a mile long by a quarter mile wide and located in the Long Island Sound to the east of the Bronx. Per an article in the New York Times, the first burial in the island’s 45-acre graveyard was in 1869. It served as a quarantine site during the 1870 yellow fever epidemic. At various times, Hart Island has housed mental patients, prisoners, and even Nike missiles. According to an FAQ by the Department of Corrections: “Previous NYC Potter’s Fields were located at the current sites of Washington Square, Bellevue Hospital, Madison Square, the NYC Public Library, Wards Island and Randall’s Island”. Today, approximately a million people are buried there in trenches containing stacks of coffins by Riker’s Island prisoners, and there are no permanent living residents. About 1,500 are added each year. New York City’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner’s site states that unclaimed remains are sent to Hart Island for burial “within a reasonable period of time.”

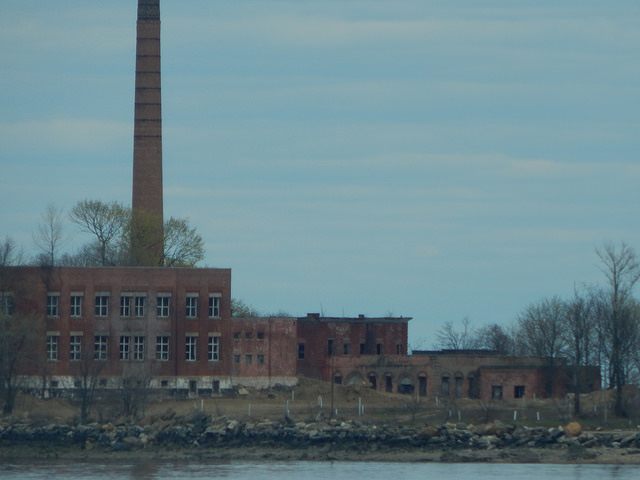

Hart Island, New York, seen from the water. More than one million dead are buried there. (Photo: Adam Moss/flickr)

Many of the bodies buried at Hart Island belong to infants and stillbirths where the mothers—much like Lusero—were often given little or inaccurate information on what this “free burial” option entailed. The person who has done the most to try and bring about a change in the status of Hart Island from prison operated mass grave to public park is artist Melinda Hunt, who has helped several women visit the graves of their dead infant children. Her website contains a trove of pictures and video from the island (including burials by prisoners) that has been closed to the public for decades. Frustrated by a lack of access to information on the city’s indigent burials, in 2009 she gained over 60,000 records dating back to 1980 which she proceeded to compile into a searchable online database. By 2012, the Department of Correction would follow suit with its own online search functionality.

While most places will bury their indigent dead in cemeteries that are open to the public, knowing who is buried where isn’t a matter of public record everywhere. In Sacramento County, approximately 250 bodies are cremated at county expense every year and buried in individual containers in a communal plot marked with a single plaque to denote the year. Michele Hernandez found out that the cremains of her dead father, a veteran, were placed there in 2007, when he was actually entitled to a military burial. The container with his cremains was moved to a military cemetery and she has sued the county. As part of the lawsuit, she also asked for the county to provide a list of all such burials—a request local television station KCRA made as well. In both cases, the requests were denied citing privacy concerns.

Washington, D.C. purports to have a similar system. Local law states that the unclaimed bodies are to be held by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for 30 days. If nobody comes forward to pick them up, a local funeral home cremates them and—according to their work order—is supposed to bury them in a way that will “allow retrieval if necessary”. In practice, they have been placed in unmarked plots in area cemeteries in Virginia and Maryland in containers which according to cemetery staff make future identification near impossible. The Washington Post reported in July that an investigation by the Medical Examiner’s office had been initiated. About 100 people per year are buried through the city’s “public dispositions” program.

Jacob Riis’ photograph of a trench at the potter’s field on Hart Island, circa 1890. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In Los Angeles, cremation is king. Their program is likely among the largest public cremations programs (aggregate statistics don’t exist for this); they cremate any one whose body isn’t claimed within 30 days (this ends up being around 1,500 people annually.). After that, county staff keep the cremains on file for an additional three years in case someone comes to claim them and pay the $400 cremation fee, which does sometimes happen. Those that remain unclaimed are all buried together in one large plot marked with the year they died during a county sponsored interfaith cemetery. There is no online database, but there are two investigators with the coroner’s office tasked with locating and notifying relatives of the decedents.

While cremation and mass burials in coffins are arguably more cost effective, in many places unclaimed bodies will receive a full burial with an individual plot. Such is the case in Fairfax County in northern Virginia and in several surrounding counties that either own municipal graveyards or pay for plots in private cemeteries. Massachusetts also pays for the burial of unclaimed bodies (a few dozen per year). Unlike affluent Fairfax County which is able to shoulder the financial burden, the Massachusetts reimbursement scheme passes on much of the cost to funeral directors and cemetery operators. Because of a law requiring explicit next of kin consent, Massachusetts funeral directors usually end up unable to get this contact information, taking away the option in practice, if not on paper.

Maryland goes in a different direction—science. The state gives authorities 72 hours to conduct a “reasonable search”, after which a body is sent to the State Anatomy Board for medical research alongside cadavers of people who had made the choice to donate while alive. Eventually the bodies are cremated and poured into a single plot similar to Los Angeles during an annual ceremony every June in which their contribution to science is honored.

In Washington DC, the unclaimed cremains are supposed to be buried in a way that allows retrieval. (Photo: Kevin Cortopassi/flickr)

Cook County in Illinois effectively allows for all forms of final disposition. If a body is unclaimed after 14 days, families are informed that it will be donated to the Anatomical Gift Association for medical research, where it will remain for an additional 60 days in storage in case there is a change of heart. If families object, the county will pay for a burial or cremation. Cremated remains can be claimed for two years prior to burial. Similar to New York City, there is a Virtual Cemetery listing the names and locations of the approximately 150 burials per year and the similar amount of names of those who were cremated.

As is evident from the numbers of burials, not everyone struggles equally with this challenge—even on a per capita basis. In Kanab City, Utah for example (population 4,468), the mayor there approves each indigent burial individually. In 30 years, there has only been one.

Handling unclaimed bodies is a grim business, one that the government is not always well-equipped to do. Instead of focusing on the dead, one jurisdiction focuses on the living—by threatening legal action if you don’t claim a body. San Diego County will send next of kin a strongly worded letter that informs them of Health and Safety Code 7103 making it a misdemeanor to not make final disposition arrangements “within a reasonable time”. The letter ends with “Please be advised that cremation arrangements with the ashes dispersed at sea and possible action to enforce the Health and Safety Code Section 7103 will be implemented ten (10) days from the date of this letter if you fail to make the necessary arrangements for the disposition of the body.”

Little wonder then that the county’s administrator expressed satisfaction in a 2012 interview that the county’s less than 400 dispositions per year had remained relatively steady and consistently cost less than the $250,000 annual budget. In nearby LA County, cremations had increased by 25 percent. Death might not respect the law, but humans sometimes do, and one letter might make the difference between an unclaimed body being placed in a mass grave and a proper burial.

*Update, 10/27: An earlier version of the story misstated the year when Melinda Hunt got access to Hart Island records.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook