Itsy-Bitsy Indonesian Rocks Are Rewriting the History of Ancient Art

The token-size stones offer insight into life 20,000 years ago.

Long before being sequestered at home meant lounging on a sofa or investing in a good internet connection, some ancient humans on the stirrup-shaped island of Sulawesi, now part of Indonesia, decided to make some art in their free time. They etched familiar things—the sun, a local bovine critter—into the stones they found. Now, 20,000 years on, those innocent little doodles are taking on newfound meaning as the first tiny figurative artworks found in the region.

“Small portable artworks … are something archeologists in this region have been searching for for a long time,” says Michelle Langley, a research fellow at Griffith University’s Research Centre for Human Evolution and the lead author of a new paper describing the find. “We now know it was just that we hadn’t dug enough.”

The 11th-largest island in the world, Sulawesi punches above its weight when it comes to ancient art. An isle peppered with volcanoes and mountains at its center, sloping into jungle and beaches on its perimeter, Sulawesi’s topography has allowed ancient remains to be preserved into the present day.

In the past few months, the island has been flipping the script on continental Europe, where most famous ancient artworks have been found. In December 2019, another group of researchers described ancient cave art that dates back farther than the famous cave murals in Lascaux, France, and Altamira, Spain.

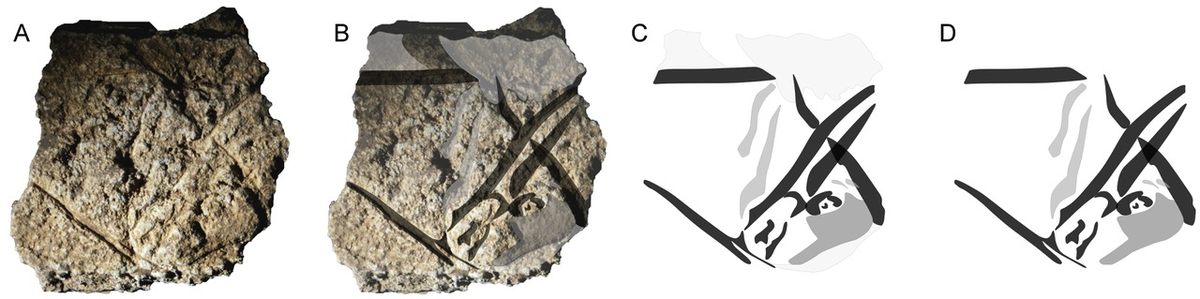

The new paper, published in the journal Nature: Human Behavior, describes two engraved plaquettes—literally “small plaques”—found buried in a pile of ancient trash. One plaquette is carved in flowstone and depicts an anoa, a small cousin of the cow (now endangered) that is unique to Sulawesi. The other—an oval carved into the center of a piece of limestone, with lines emanating from it—resembles a celestial body. The anoa plaquette, the researchers say, is the first bas-relief found outside Europe.

While the “sunburst” plaquette was identifiable from the off, the subtler incisions on the anoa plaquette—which is a bit deteriorated, if you can believe it, from its 20 millennia in a Sulawesian rock shelter—had to be put under some high-quality lighting to be discerned.

“At first I thought I might be seeing things, though I became more convinced the more I looked,” Langley says. “We were pretty excited about the identification of an engraved animal—we knew it was a first.”

The ancient Indonesian artworks are pint-sized, akin to ancient European figurines—probably so that they were easily portable for the residents of Pleistocene Sulawesi. The presence of such mini-works moves the needle of archaeological equity a bit, by highlighting that early groups in Southeast Asia worked on art projects similar to their European contemporaries.

“We hope that people are able to appreciate and celebrate the similarities and diversities of our first cultures and communities the world over,” Langley says. “People 20,000 years ago were doing some pretty interesting and amazing things in Africa, in Europe, in Asia, and in Australia. We are only just scratching the surface of the complexity of people living back then.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook