Fun Ways to Get Kids Into Photography

“Invite them to capture the way they see the world.”

The oldest surviving photograph, taken by French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1827, was of the view out his window. The image took several days of exposure to sunlight—with a method that used an entire room (called a “camera obscura”) to yield a faint impression of buildings and trees from his family’s estate in Burgundy.

Photography has come a long way since then. Today we take for granted how pocket-sized smartphones can capture countless incredibly detailed images in a fraction of a second. With such speed and convenience at one’s fingertips, literally, it doesn’t take an inventor or a professional to take amazing photos. All it takes is an eye, and kids certainly have that—especially in the age of Instagram. Texas-based photographer Justin Hamel writes in an email, “I find that kids … are much more used to thinking visually than anyone my age (30s) ever was because of growing up with so many devices and photo-sharing apps.” Atlas Obscura spoke with some professional photographers about how to entice kids to focus their perspective and curiosity on more than random selfies.

Give them a scavenger hunt.

Make an adventure by asking kids to find specific things with their lenses, which could be on a phone, a tablet, or a dedicated camera. When architectural photographer Matt Lambros’s very young daughter started pretending to “take pictures like daddy,” he gave her a children’s digital camera to take on their daily walks in the yard during the pandemic. He says, “We started with taking pictures of things of a certain color (four pictures of something red, something blue, etc.) to searching for flowers or bugs to photograph.” Besides color and objects, travel photographer Erin Sullivan, based in Los Angeles, also suggests trying to search for more subtle things to shoot, such as different kinds of light or texture. She says, “So much of photography is about noticing.”

Give kids permission to obsess.

Get young shooters excited to see familiar things anew by having them photograph a single object, person, or pet in 10 to 20 different ways. They learn about point of view and attention to detail. When Portland, Maine, photojournalist Greta Rybus taught photography to kids, she instructed them on “angles and perspectives by having them photograph from an animal’s viewpoint: a bird, an ant, a dog.” Multiple people doing this together can make it even more informative and insightful. Mallika Vora, a documentary photographer currently based in Mexico City, suggests that “at the end everyone can compare their results and talk about how they see the same thing differently through a lens. This is a good way to explore perspective, and show how every person looks at things in their own unique way, and how the same subject can be represented in infinite ways.”

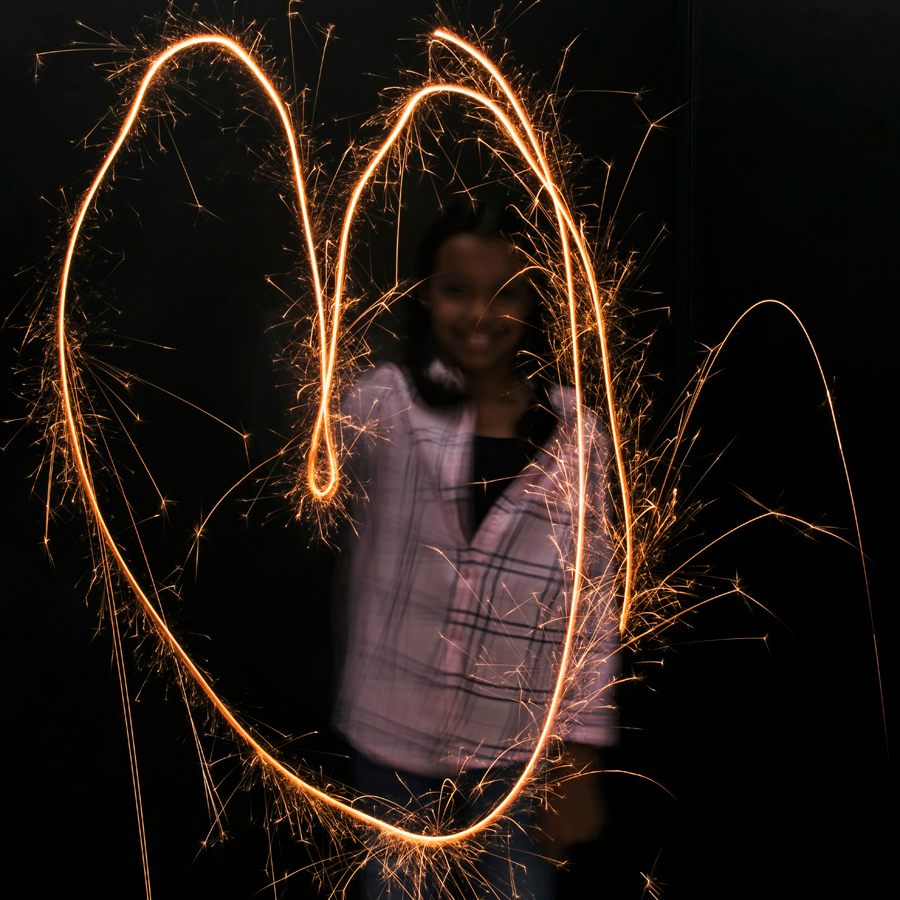

Paint with light and motion.

The word “photography” comes from Greek: “drawing with light.” An entertaining photo activity “that can keep you busy forever is painting with the light” during a long exposure, according to Matjaž Tančič, a photography artist based in China. First set the camera (a phone or tablet with an app that has manual controls works) on a tripod or flat surface in a dark room, then set the exposure time to a minute. With a flashlight, lit cell phone screen, or small lamp, he says, “you can put the light on yourself, then move, light yourself again, and keep going. You will see your clones in the photo.” Or use the light source to create glowing drawings in the air. Hamel recommends “glow sticks or sparklers (if you’re outside) and see all the fun designs they can make.” Long exposures by themselves can still be intriguing. “I think that slowing the shutter down to a few seconds and letting [kids] run around and create blur is exciting,” he adds. More importantly, especially if you’re sheltering in place, he says “it’s a way for [the kids] to get some of that pent up energy out.”

Invite kids to tell their own stories.

Older kids can convey complex and meaningful ideas with photographs through composition, multiple images, or adding words. Something as simple as cutting a rectangle out of cardboard to make a frame can be a powerful tool. Rybus says to let kids “walk around, using the cardboard hole to consider how composition can be used to include or omit information.” The young photographers learn that by choosing or not choosing to include certain things—people, shadows, movement—in the frame, the story and impact of their pictures can change.

Having them compose stories with images can be a critical exercise. One photo can add meaning to another, especially when limited by a time frame, such as a day. In the time of the pandemic, Jerusalem-based photojournalist Heidi Levine, who teaches workshops, suggests asking kids to document the poignant scenes around them, such as “their own bedrooms, maybe still images of a dress they were hoping to wear to a party, capturing images of their Zoom calls with grandparents, the daily washing of food deliveries that come into the home, and so on.”

Adding actual words can be valuable, too. “I believe that if [kids] get into the habit of writing down a paragraph or more a day to accompany their images, then that would create a really nice visual journal that could be uploaded and shared in some way between the students and remain an important historical document,” says Levine. “It could … bring the students closer together as they share a sliver of their lives with one another.”

The technical and storytelling skills kids develop in the home will be useful when travel is possible again—and on simple, local jaunts. Travel and documentary shooter Mark Edward Harris writes in his book, The Travel Photo Essay: Describing a Journey Through Images, “Your own hometown will undoubtedly have some hidden and not so hidden treasures that could yield great travel photo essays. After all, where you live represents a travel destination to someone else. You don’t always have to get on a plane or train or even in a car to generate a dynamic photo essay.“

Remember that it doesn’t matter whether kids have the eye or technical prowess of Cartier Bresson or Annie Leibovitz. It’s about process and experimentation and expression—“invit[ing] them to capture the way they see the world,” Sullivan says. The results are not as important as how it makes kids feel. “When you’re getting into it,” Hamel says, “there’s no such thing as a bad photo. It’s all about having fun.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook