The Uncertain Future of the World’s Largest Secondhand Book Market

At the College Street market in Kolkata, India, independent booksellers fear the arrival of a massive mall.

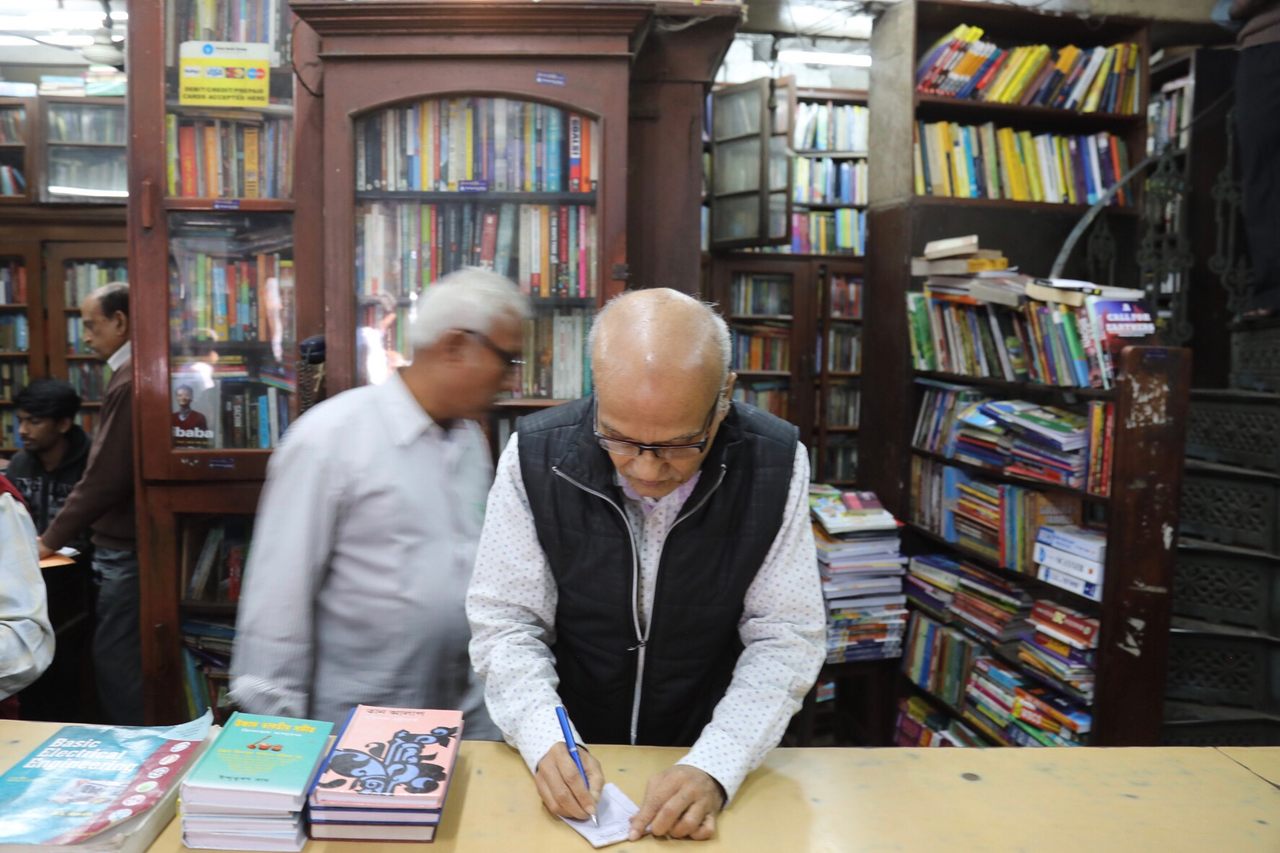

Shortly after dawn in Kolkata, India, musky plumes of incense waft through the passageways of Das Gupta & Co. bookstore, diffusing among the decades-old volumes on its steep mahogany shelves. The smoke billows out of the shop’s peeling, pale-blue doors and onto Kolkata’s College Street, the largest secondhand book market in the world.

Each morning, as part of a common Hindu tradition known as puja, a daily prayer ritual usually intended to praise a deity, the bespectacled Arabinda Das Gupta swings a brass censer around his old shop. He is a fourth-generation bookseller; the object of his worship is the written word. “Puja concentrates your mind on the books,” he says. “There’s chaos and movement before, but then the words go still like grains of rice. I need that sense of calm to go about my day’s work in this place.”

Das Gupta’s shop is the oldest in the entire market. When Arabinda’s great-grandfather, Girish Chandra Das Gupta, arrived in Kolkata in 1886, he had little competition. “Very few books were available at the time, so he imported them to meet demand,” he says. The shop opened that year with a noble mission: “the spreading of knowledge.” It had just 50 books.

Nowadays, the market can trade that many books in a few minutes. College Street, known by locals as Boi Para (which roughly translates to “Book Town”), spans more than a mile and covers a million square feet. Bigwigs of Bengali publishing coexist with makeshift stalls hammered together from wood, bamboo, tin, and canvas, in a chaotic matrix that runs from Mahatma Gandhi Road to Ganesh Chandra Avenue.

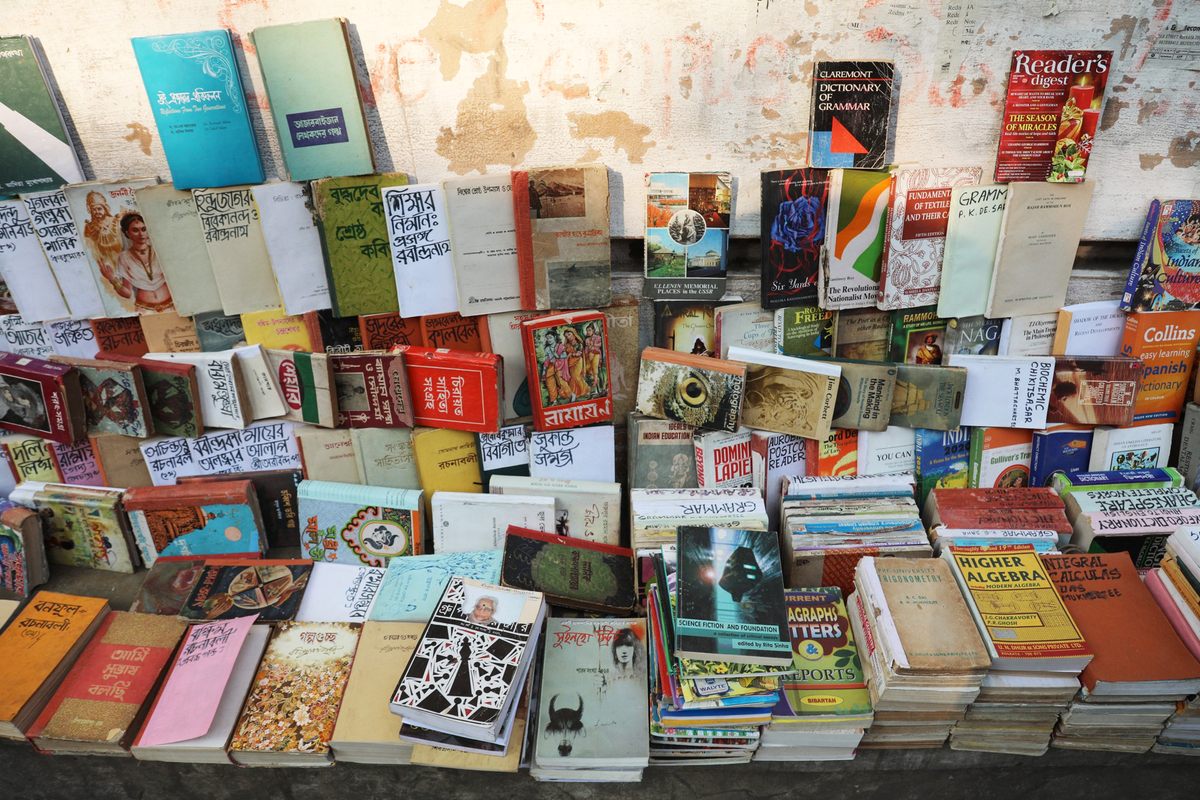

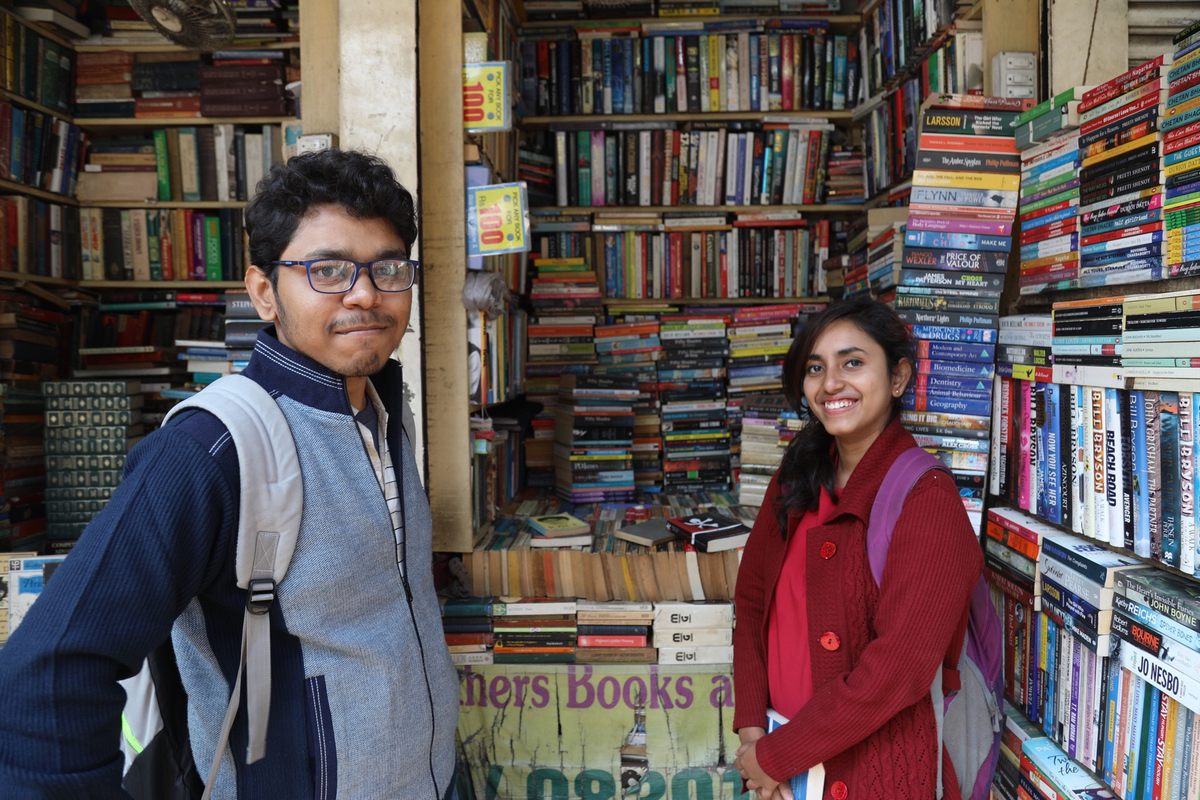

College Street has every imaginable type of text, available in Bengali, English, Mandarin, Sanskrit, Dutch, and every dialect in between. Precious first editions and literary classics sit cheek by jowl with medical encyclopedias, religious texts, and pulp fiction, often precariously stacked in uneven piles that resemble jagged cliff faces. Wily booksellers peer from raised wooden stalls; bearded collectors rifle through stock; mothers drag first-year university students through the aisles to collect their required reading.

The old-world charm of College Street may not last forever, however. Flyovers and shopping malls have sprung up across the city, courtesy of rapid modernization projects that are flattening unique histories. More than a century after the book market was founded, some booksellers are worried that change is coming to College Street.

Kolkata’s rich literary heritage dates back to the 18th century, when the East India Company helped to make it a major printing center. Under Lord Wellesley, the British colonial governor who organized construction of the city’s central roads, the Hindu College was built in 1817, later followed by the Calcutta Medical College, the first medical school in the country, in 1852 and the University of Calcutta in 1857. These colleges set up a syndicate with several shops in the 1870s, catering to India’s intelligentsia and British colonizers alike, and College Street market was born.

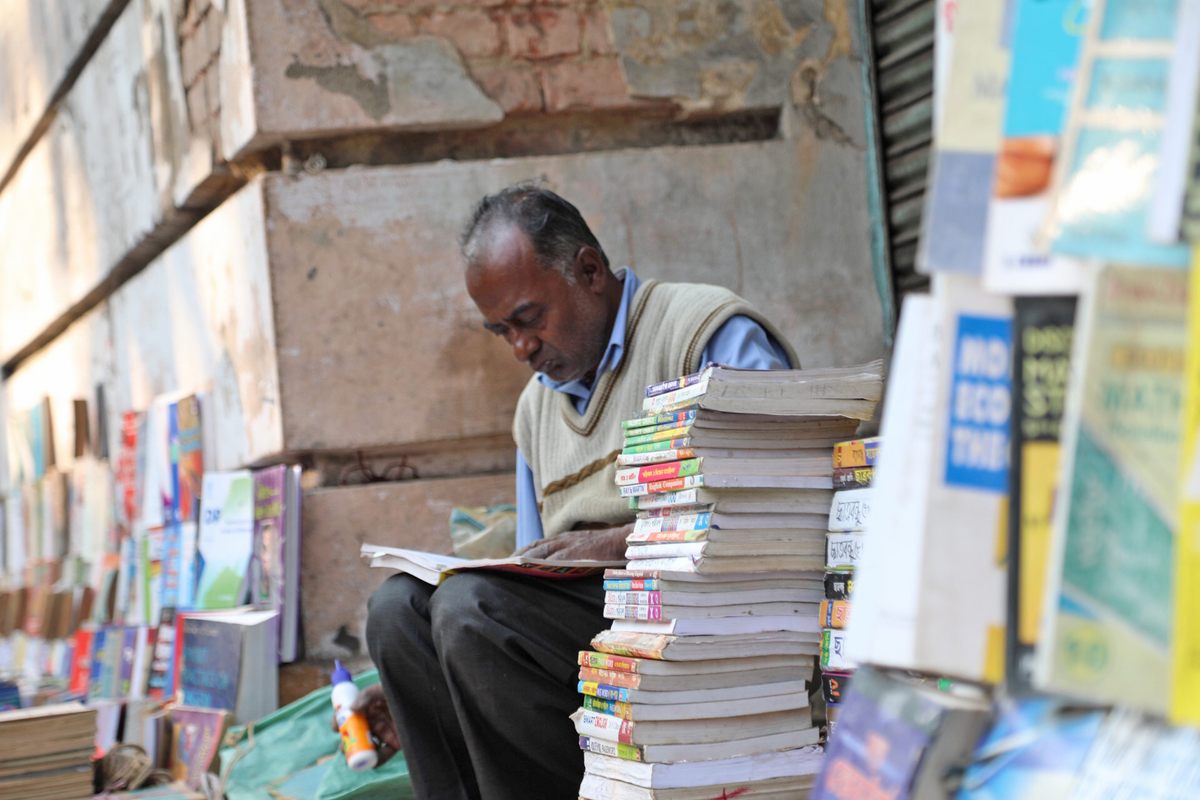

Decades ago, the British poet and translator Joe Winter described College Street as “a planet littered with books, a crazed sales pitch wherever one looks.” His description still rings true. Yellow and green tuk-tuks, or auto-rickshaws, fly by; men drag carts of books; bicyclists squeeze through narrow gaps with bags of books balanced on their handlebars. Even more books arrive on the city’s technicolor buses and yellow taxis, which are shaped like turtle shells.

“Although books aren’t a necessity like they once were, with so many alternative ways of getting information, somehow we keep going,” says Pinaki Majumdar of APC Ray, arms tucked pensively behind him. He wears the unofficial College Street uniform: a striped, short-sleeve shirt and a round belly that belies the sedentary lifestyle of a reader and Kolkata’s fried street food. Majumdar is one of the longest-serving of the cheeky, chattering booksellers. APC Ray bookstore was set up in 1910, boasting of rare editions from Bengali greats such as Rabindranath Tagore and Jibanananda Das. “Books are everything to me,” adds Majumdar. “I started reading when I was just five years old and never stopped. I even love them more than my wife.”

But a new development could cut deeply into the business of the hawkers who have thrived here. For years, the state government has been pushing ahead with an ambitious, centralized book mall that will stretch over a million square feet, as large a floorspace as all of the existing bookstores combined.

According to the project’s architects, the Barnaparichay Mall is to launch next summer, and will offer sleek, modern boutiques, a library, an auction center, translation services, and cafés. “The mall is to enrich the book culture and habits of Kolkata,” says Sankalan Tatar, of the architecture firm Prakalpa Planning Solutions. “It will be an integrated book mall. Literature, life, and leisure will be under one roof. This will be the most happening place in north Kolkata.”

Traditional booksellers fear that the mall will threaten the traditions of College Street. “The place will be soulless,” says Das Gupta. “But I’m worried that people will prefer the cheap prices and comfort of the book mall, so I’m considering taking a place there.” For some of the less-established booksellers, the mall’s rental prices will be prohibitive. “The book mall is too expensive for me to move,” says Ranjit Biswas, owner of a cupboard-sized stall full of dusty books. “I couldn’t even if I wanted to.”

According to Tatar, some concessions will be made. For example, on Sundays, the mall’s escalators will be switched off for two hours, allowing the makeshift booksellers to come into the mall and ply their trade in certain spaces.

Many booksellers remain unconvinced. At the market’s famous Indian Coffee House on Bankim Chatterjee Street, a historic meeting spot for Kolkata’s writers and thinkers, the mall is a constant subject of adda, the Bengali art of wide-ranging conversation, often practiced here among students.

Akashleena Bhaduri, a third-year engineering student at the University of Kolkata, sips on a sugary coffee and makes the case for the book mall. “This place is outdated, the roads are dirty, the hygiene is poor, and in the summer it’s unbearably hot,” Bhaduri says. Ohit Banerjee, a postgraduate researching comparative Indian language and literature, fires back. “My elders told me that Mahatma Gandhi bought a rare book from here, and that he said it was a special place,” he says. “We must protect it.”

Whatever awaits Kolkata’s College Street in its next chapter, the community has already survived innumerable challenges. It has been through two world wars, has managed to remain a center of political and literary activism since the 1930s, and witnessed the beginning of the revolutionary Naxalite movement in the 1970s. According to Das Gupta, violent protests broke out against the stocking of controversial books, such as D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. On May 30, 2004, his shop suffered a fire that caused enormous damage and destroyed maps of Bengal dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries.

Still, College Street has gone on to become the beating heart of India’s literary world, with intellectuals such as Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, a Harvard economist and frequent visitor, making it a home away from home. Institutions such as the fifth-generation Bani Library, known for its science collection, and Sri Aurobindo Pathamandir, a religious center established in 1941, has made it a pillar in the city’s identity. These achievements, the booksellers say, can never be taken away.

During a rare moment of afternoon calm, Das Gupta sits down for a chai masala, boiled in huge pots and served in tiny, ceramic cups. In the background, booksellers lean lazily over their stalls; others squat down low to gossip, or calmly leaf through thick tomes. There is a sense of togetherness. “This is the way that I see it,” he says, widening his silver eyebrows. “We’ve written this history and we won’t be forgotten.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook