An Engraved Tomahawk Offers a New, Native History of a Battle

The weapon may have belonged to a Lakotan warrior named Stranger Horse.

On July 26, 1865, two young men met on a battlefield in what is now Wyoming. Both were 21, young leaders of their respective forces. Stranger Horse, a Lakota, fought alongside a coalition of Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho warriors. Caspar Collins, a second lieutenant in the Ohio Volunteer Cavalry, fought for the U.S. Army. The Native American forces won decisively—outnumbering the 150 U.S. soldiers with a force in the thousands—in one of the few Native victories during that period, when settlers and soldiers violently pushed Native Americans off their land to shrinking reservations. Western history documents the demise of Collins—riddled with 24 arrows and, by the time the dust cleared, without hands—and the outcome of the Battle of Platte Bridge, fought near the modern city of Casper (named for the fallen lieutenant, despite the typo). But there’s no mention of Stranger Horse, or the fact that he was the one who killed Collins. That history’s been newly revealed—on a tomahawk.

“Both were protecting their ways of life,” says Donovin Sprague, a visiting professor in Indian American Studies at Sheridan College in Wyoming and a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. “One ends up dead, with a city named after him, and the other becomes a chief.”

The 19th-century weapon in question features detailed engravings, and was found in late 2019 at an estate sale by artist Bob Coronato and collector Larry Robinson, according to Sprague. “This is the first confirmation I know that Stranger Horse was in the Battle of Platte Bridge,” Sprague says, since much of what historians know of this battle comes from the perspective of the U.S. Army. “These stories have been handed down for many years, but much has been forgotten.”

The Battle of Platte Bridge was not a one-off altercation in the American Indian Wars that had roiled North America for centuries, but rather a calculated act of vengeance for the infamous Sand Creek Massacre. The year earlier, on November 29, 1864, 675 U.S. soldiers ambushed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho people in what is now southeastern Colorado, killing and brutally mutilating 148 Native Americans who had been awaiting peace negotiations. The soldiers then displayed the heads of their victims. “That’s when the Cheyenne brought the war pipe to our family and asked us to join in warfare against the United States,” says Sprague, who is a descendant of the chiefs Crazy Horse and Hump, also called High Backbone, who was Crazy Horse’s uncle. “The next big engagement was Platte Bridge.”

By the following May, a coalition of Native warriors assembled, and they then attacked U.S. soldiers stationed at Platte Bridge Station, a post guarding an Oregon Trail crossing on the North Platte River. They were led by several chiefs, including Young Man Afraid of His Horses from the Oglala Sioux and Crazy Horse from the Oglala Lakota, writes historian Kingsley M. Bray in Crazy Horse: A Lakota Life. The identity of the man responsible for Collins’s death, however, was a mystery for years.

Now this engraved tomahawk appears to have answered that question. Coronato first learned of the tomahawk when a friend stumbled upon it at an estate sale in Arizona. “Only one out of a thousand of these finds is real, but this was real,” Coronato says. Believing the weathered weapon could have belonged to a warrior at the Battle of Little Bighorn, he sent images to his friend Mike Cowdrey, an independent scholar and expert in Plains Indian ledger art, a tradition named for the accounting books that it was often made with.

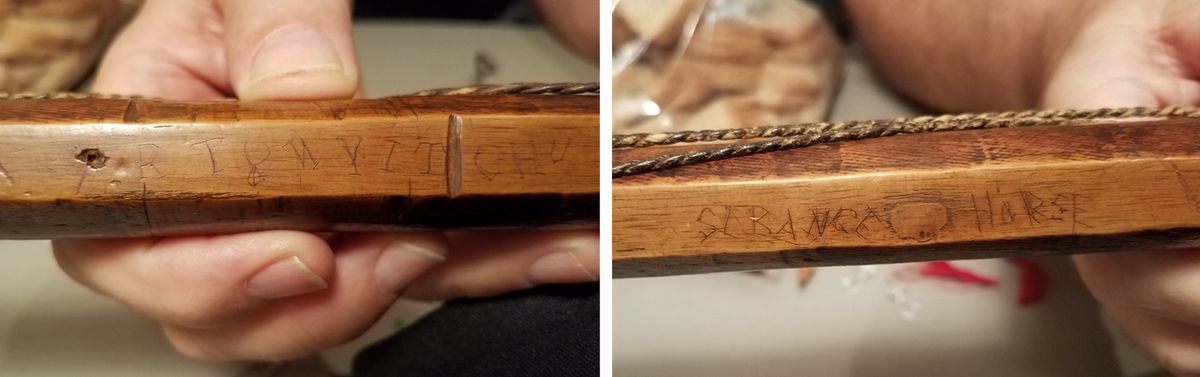

The tomahawk had heft, with pink and green beaded decorations and a handle made of ash that also functioned as a pipe. “Strange Horse” is carved into the wood in both English and Lakota, indicating it belonged to the Lakota chief himself. (He was called both Strange and Stranger, but Sprague prefers the latter.)

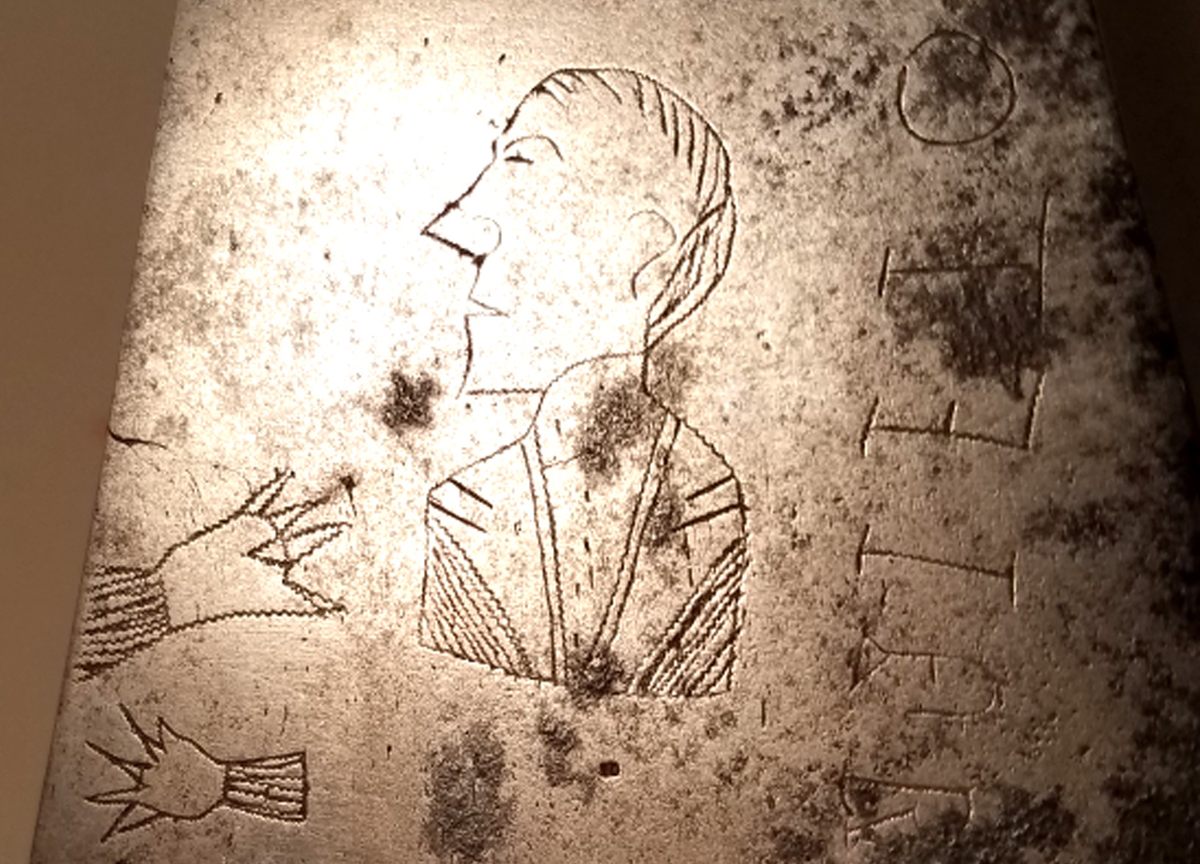

The most notable thing about the tomahawk is its blade, blacksmith-forged steel with engravings that depict several scenes, including a horse figure and tracks symbolizing successful raids against enemy tribes, according to Cowdrey’s notes. Most notably, it depicts the torso of a cavalry officer in the U.S. Army—with his throat cut and his hands removed. The illustrations were made with a technique called rocker-engraving, a technically difficult style in which the artist rocks a chisel back and forth to make indentations in metal. According to Cowdrey, the engraving is as good as a signed confession.

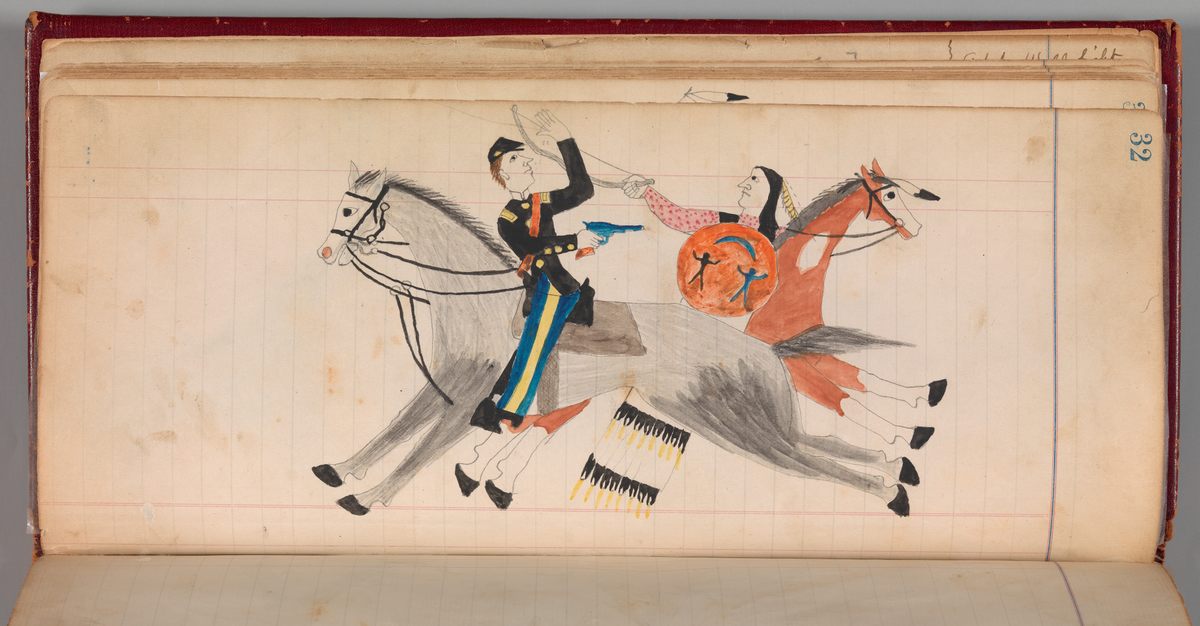

Much of Lakotan history—at least, as told by the Lakotan people, not settlers—is pictorial, Sprague says. For example, many Plains tribes in North America documented their experiences on winter counts, buffalo-hide calendars that mark each year—first snowfall to first snowfall—with a picture depicting its most memorable event. “My challenge is to get the world of science and academia to say, ‘Yes those are valid sources,’” says Sprague, whose history Rosebud Sioux uses winter counts as primary sources. “Even though I am not referencing a book, I am referencing what we now know is a primary source.” For example, Sprague used a winter count to confirm the story he’d heard as a child of how his great-great-grandfather Hump died in battle; his parents told him Hump’s gun had misfired. “I found the winter count drawing, and he’s drawn holding his arm out with the pistol dangling toward the ground,” he says, suggesting that a broken firearm was involved in his death. “It helped to connect the dots.”

The Lakota had passed down tales of Stranger Horse in oral histories, but he had never been depicted in a winter count, and no one knew whether he had been present at the battle. By placing Stranger Horse at the Battle of Platte Bridge, the tomahawk actually complicates the traditional tribal understanding of the battle, Sprague says. “It’s normally summarized as ‘Red Cloud’s War,’ led by Oglala Lakota chief Red Cloud and his warriors, but now we know there is much more to it,” Sprague says. According to Sprague, Stranger Horse’s descendants, who live on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, do not yet know about the tomahawk, but he plans to tell them about the object when he visits.

Coronato, who has been displaying the tomahawk in his small gallery and museum in Hulett, Wyoming, hopes to place the artifact in a larger museum in the state. But it wasn’t cheap, and he does not plan to donate it. If a museum can’t find the budget, the tomahawk might land in the hands of a collector.

“It would be awesome to display the tomahawk right around the site of the battle, by Casper,” Sprague says. But in Sprague’s eyes, the knowledge alone, gleaned from the tomahawk, helps to fill out and sustain the history of the Lakota people, otherwise spread thin in stories and objects. “It’s all family history,” he says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook