Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Little-Known Forays Into Judaica

The stained-glass artist created mosaics, menorahs, and bronze synagogue doors.

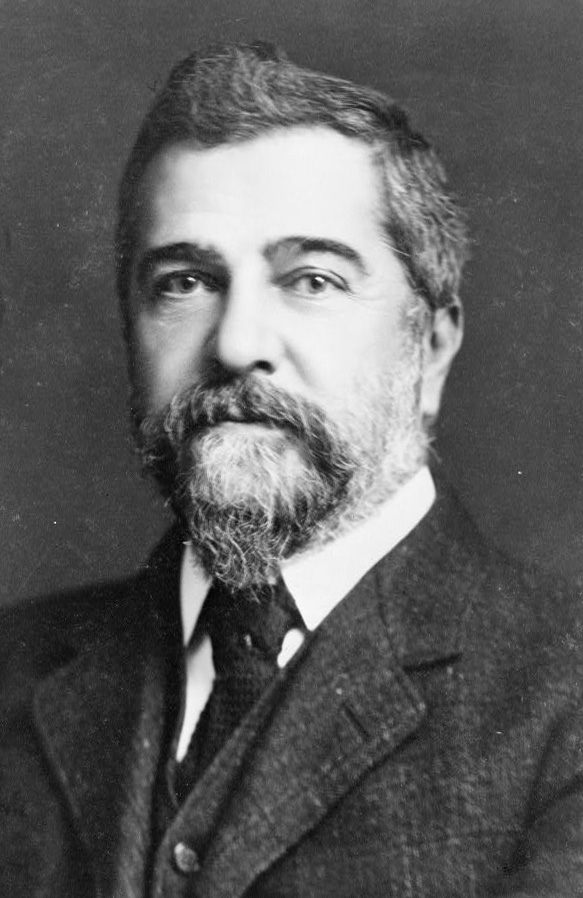

Louis Comfort Tiffany kept plenty of ridged milky glass panes on hand, to use in depictions of saints’ robes and angels’ wings for his sought-after stained-glass windows. From the 1880s to the 1930s, his workshops in Manhattan and Queens supplied American houses of worship with thousands of windows, portraying Biblical figures against backdrops of Holy Land sites. The designs have been the subject of scholarly studies, and they have even been adapted for coloring books and greeting cards. But until a year or so ago, hardly any connoisseurs realized how many clients in this niche Tiffany ecclesiastical market were Jewish.

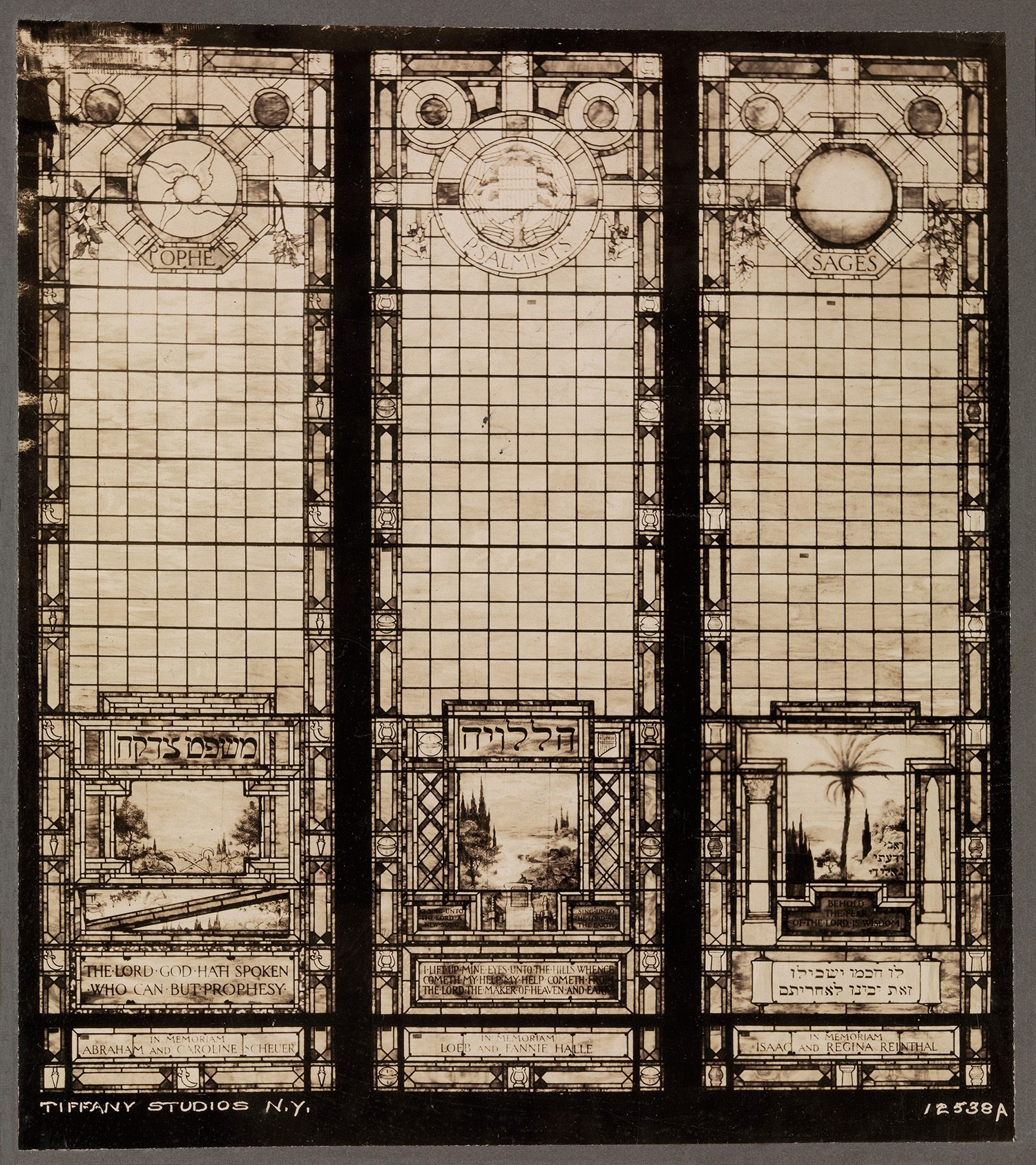

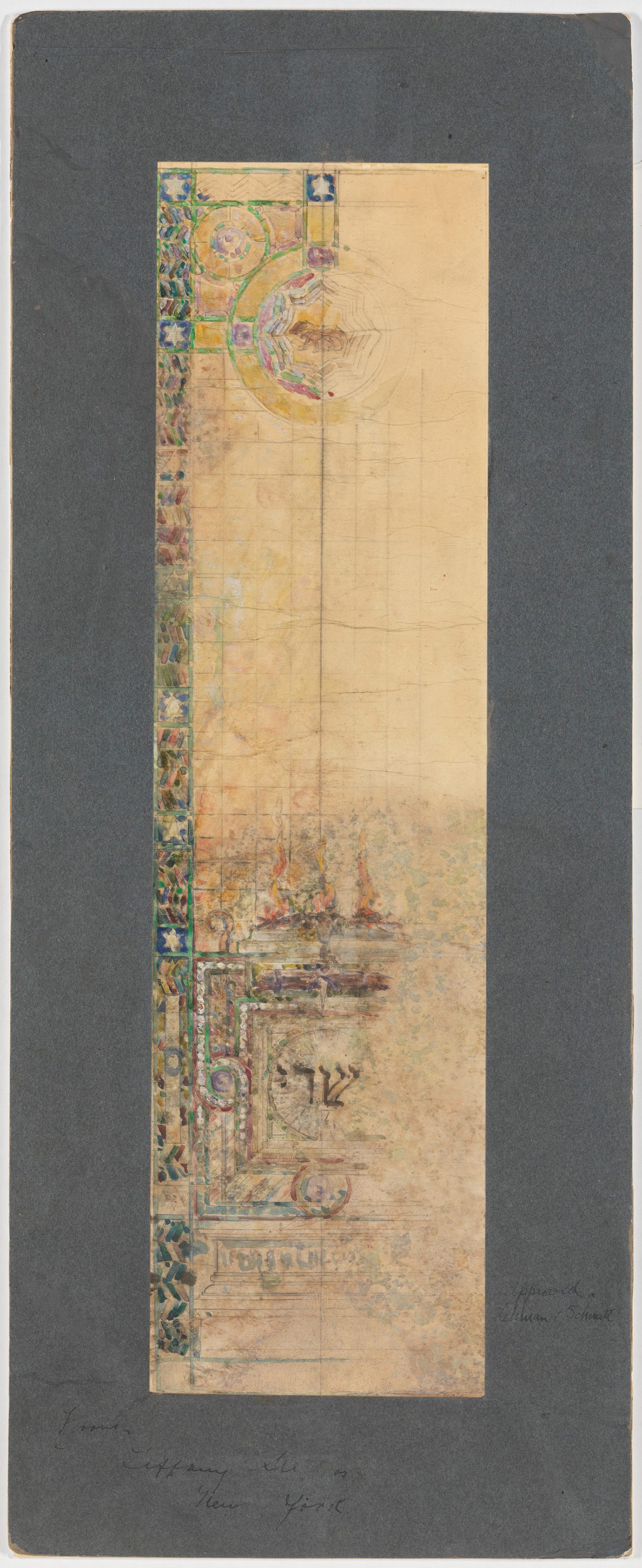

Tiffany, who was raised Presbyterian in great privilege (his father Charles founded the Manhattan jewelry store that bears the family name), worked with rabbis from Manhattan to Michigan. He created synagogue windows inscribed in Hebrew as well as related mosaics, bimahs, menorahs, bronze Ark doors, and embroidered textiles used as Ark curtains and Torah scroll wrappings. Dozens of the pieces survive, along with photos and other documentation of Tiffany’s lost Judaica that was destroyed by fires or demolition crews. Dr. Patricia Pongracz, the executive director of the Macculloch Hall Historical Museum in Morristown, New Jersey, has set out to document the forgotten works made for synagogues and Jewish cemeteries.

Tiffany seems to have not shared the anti-Semitism that was prevalent in his social circles, as he catered to Jewish immigrants and their descendants. “In all religious denominations, the desire for beauty is everywhere uppermost,” he wrote in an 1893 essay on art glass. He advertised his wares in Jewish newspapers, whose readers were commissioning eye-catching turreted structures in American downtowns. By hiring the New York tastemaker who had worked for so many Christian sects, synagogue patrons could communicate their new artistic sophistication and cultural assimilation. The buildings’ underlying messages, Dr. Pongracz says, was “we have arrived.”

Tiffany had traveled widely and collected artifacts from every continent; he found aesthetic inspiration in everything from vistas of Mexican volcanoes to knot motif inlays on Italian church floors. He helped design synagogue interiors in New York’s Albany and Buffalo, Baltimore in Maryland, and Grand Rapids, Michigan, among other places, and he fabricated Stars of David, Ten Commandments tablets and Old Testament scenes out of layered opalescent glass. His windows and mosaics were also installed in Jewish mausoleums—in some cases, those valuable pieces (worth tens of thousands of dollars each) have been removed from the graveyards and reinstalled inside the communities’ synagogues, for protection from theft.

Dr. Pongracz has found Tiffany’s renderings, correspondence, and receipts in synagogue archives and other institutions’ files. The Metropolitan Museum of Art owns Tiffany’s rendering of bronze Ark doors from the 1910s, which are installed in a side chapel at Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue. The Met also has a Tiffany sketch for grid-pattern windows trimmed in Jewish stars and Holy Land scenes, which were shipped to a Cleveland synagogue now used as Liberty Hill Baptist Church. (Dr. Pongracz has reported her findings in the Met’s journal, and she is working on further writings on the subject.)

A particularly large concentration of Tiffany’s Judaica survives in Manhattan. Temple Emanu-El, along with its bronze Ark doors, has preserved at least three windows from Tiffany’s workshop, with views of Holy Land stone structures, Moorish colonnades and waterfront sunsets. At Shearith Israel on Central Park West, the main sanctuary is illuminated floor to ceiling by Tiffany windows in muted pinks, greens, blues and ambers. The panes are shaped like fish scales, scrollwork and flower petals, and some are streaked to resemble abstracted desert landscapes. Their palette seems to shift with the seasons and time of day. Barbara Reiss, Shearith Israel’s executive director, says that when sunrise over Central Park pours through the glass, “it’s heavenly rays.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook