The Blogger Quietly Preserving Maryland’s Culinary History

Kara Mae Harris hopes to archive every local cookbook.

In the library of the Maryland Historical Society, Kara Mae Harris sits at a large table with fragile manuscript pages and her laptop. She taps away, entering recipe after recipe from centuries-old cookbooks, diaries, and handwritten pages into a database of more than 24,000 entries. She’s not a historian or chef, but she has dedicated thousands of hours to preserving Maryland’s unique culinary traditions, and every week, she tests a recipe and puts the history behind it on her blog, Old Line Plate. Harris enjoys uncovering and sharing history that no one else is talking about. Once she realized the vastness of Maryland’s food history—and that almost no one was singularly focused on keeping a record of it—she’d found her new project.

Harris grew up in Maryland outside of Washington, D.C., a place that sometimes loses its identity in an amalgamation of suburbs. She had never contemplated her home state’s culinary identity. “I never thought of Maryland as the South. I didn’t know anyone who did,” she says.

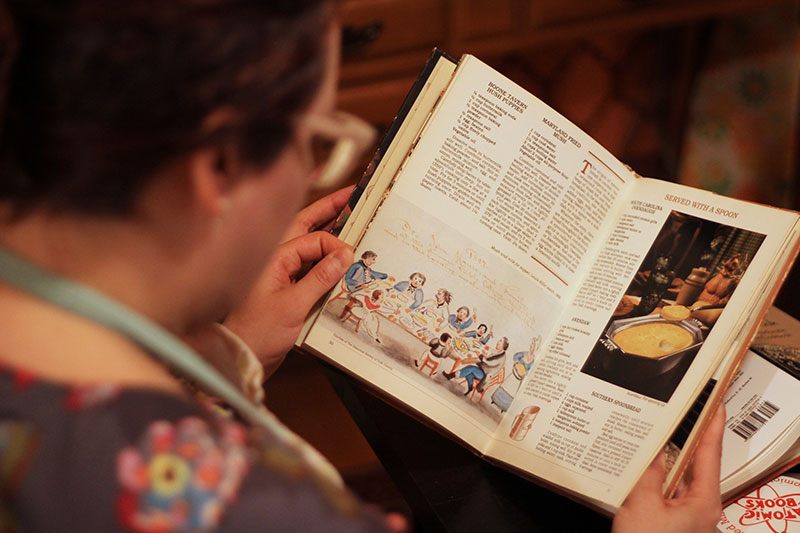

“These books are how I learned Maryland food was even a thing,” Harris adds, as she picks up an issue of the Southern Heritage Cookbook Library. She started reading books like this one since she was interested in cooking, but was surprised when she found recipes from Maryland. She was fascinated by the ephemera and history that the cookbooks offered with each recipe, and she became interested in the foodways of Maryland, a state shaped by its unique geography: on the East Coast, on the line between the North and the South.

“Once I started studying the food, I realized that culinarily, Maryland absolutely is the South,” she says, even though she knows that conflicts with how many people feel about the state.

In 2011, Harris started Old Line Plate (a pun on Maryland’s nickname The Old Line State), and she mostly drew from the cookbook Maryland’s Way, a collection of 18th-century recipes. That led her to more cookbooks available online and recipes in old newspapers, and soon creating a database to keep track of all the recipes took precedence over the blog. Harris loves history, but she also loves data. She believed a database would allow her to more easily analyze trends, trace information, compare and contrast recipes, and then share her findings with anyone who was interested. When she’s not at her full-time job (as a college admissions officer), cooking, or blogging, she goes to the Maryland Historical Society, the Enoch Pratt Free Library, and smaller historical collections in the state to diligently enter recipes into her database.

What she has made should be the envy of most every food historian and librarian. Each recipe entry includes the cookbook it came from, the person who wrote the book, and relevant tags, such as other names for the same recipe or key ingredients. The database is searchable by any of those fields. Harris resurrected the cooking blog in 2015, and has been posting weekly recipes and histories for the last two years, using research from her database.

She recently read that the first appearance of fudge at a Vassar College bake sale (and subsequent popularity across the country) was connected to a recipe derived from Baltimore, Maryland. “After I found out that fudge allegedly is Baltimore-centric, I isolated all of the fudge recipes [in the database], and there are almost 80 of them,” Harris says. She then looked at the recipes and saw that Baltimore fudge (or caramel, as it is called in old cookbooks) is brown-sugar based, like the Vassar recipe, while others had molasses. The database allows her to see the history and lineage of a recipe.

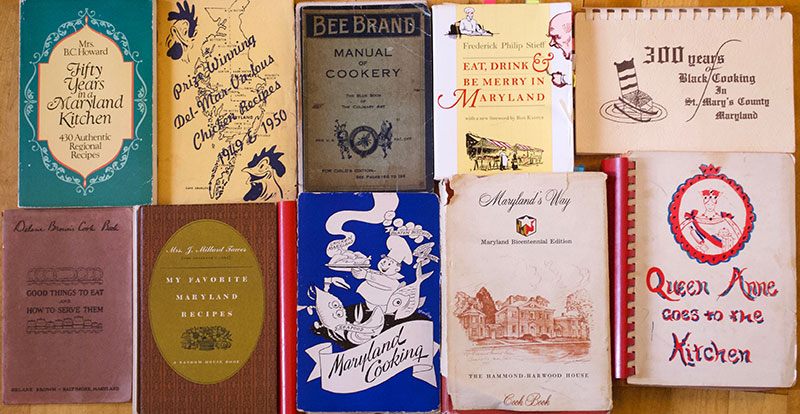

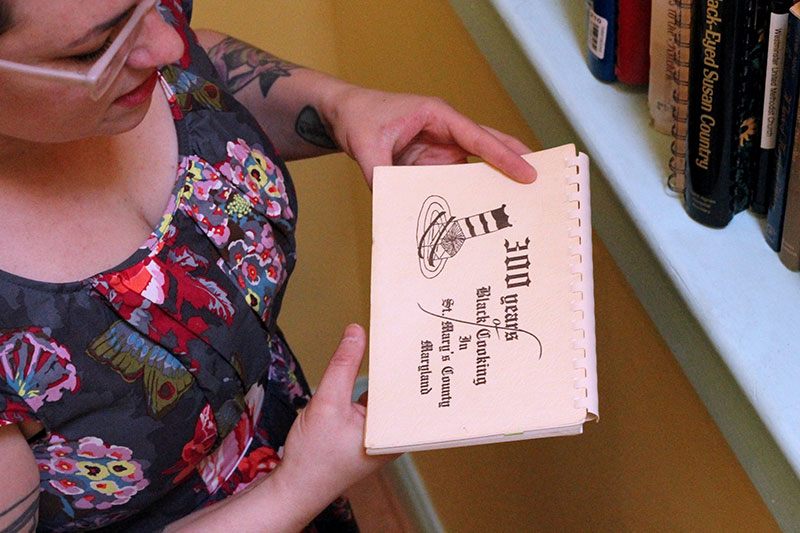

At home, Harris has a long shelf of Maryland cookbooks, and right now one of her goals is to get every pre-1900 cookbook entirety into the database. Eventually, she wants to add the hundreds of published, semi-published, and unpublished Maryland cookbooks. Harris finds this monumental task soothing and affirming. “I’m not super credentialed,” she admits, “but I can immediately open a book and know so much about this person and their economic status and their family and the year that it was made, just by what they are cooking and what type of recipes they are writing down.” This gives her great pleasure.

Harris also values sharing her findings. When she posted a recipe from a community cookbook, she received a request from one of the contributor’s family members for a copy of the book. She then proceeded to scan the entire cookbook. “That’s their food, that’s their recipes,” she says. Harris wants to make sure everyone from Ph.D. students to Maryland residents to chefs have access to these recipes. She’s donated her oldest books to the Maryland Historical Society, and she posts a spreadsheet of her database on her blog. (Although this public version doesn’t currently have tags.) In an age when digitization rules, Harris believes that sharing these recipes online will help keep traditions alive.

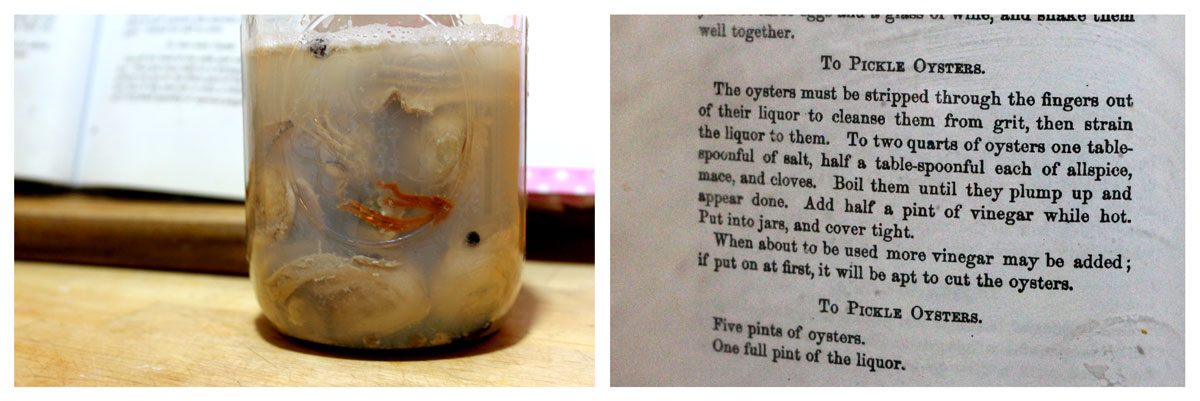

One of the problems with old cookbooks is that they often lack the storytelling we find today in food blogs and glossy cookbooks. “The cookbooks barely tell you how to make things,” says Harris. They don’t have photos; they don’t list ingredients and steps; they don’t tell you where they got the recipe; they don’t even tell you at what temperature to bake.

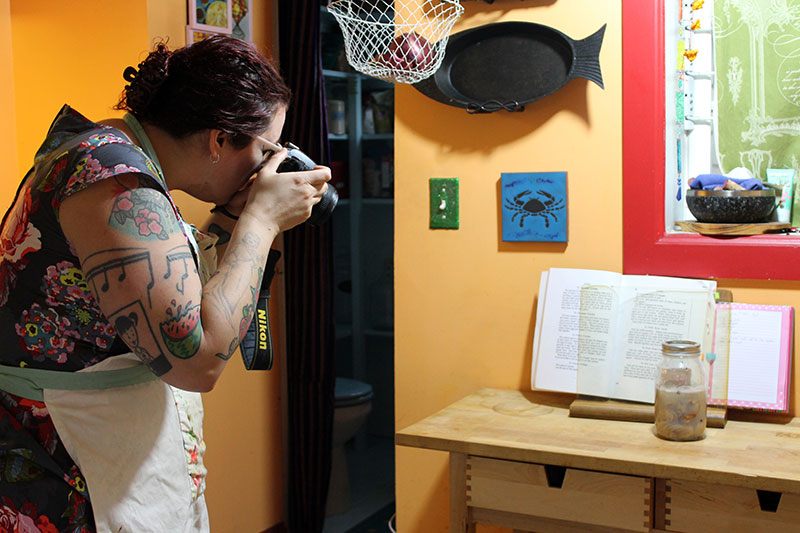

When Harris made pickled oysters, a dish that feels very Chesapeake-Bay-meets-Eastern-European-Immigrants, the recipe simply had the ingredients and how to add them together. “I’m going to spend the next days trying to find out what people actually ever did with these,” she says. And that’s one of the benefits of the database and the blog. Harris searches through newspapers and other cookbooks to find out more about when the dish would have been eaten and how we experience food differently today. This enlivens old recipes and history, making them more approachable to modern cooks.

And while many people might open an old cookbook and find the recipes unusual, Harris says that “Weird is relative.” Even dishes such as oyster ice cream or noyau (a liquor made from peach pits) don’t seem that strange to her anymore. “A lot of the stuff people think is weird is just the lost concept of umami in western food. It was totally there, people were using funky oysters and mushroom powder and anchovies, and for some reason just stopped.” She wants to figure out if they are worth making based on modern tastes, and reintroduce her readers to lost foodways they might enjoy.

Even though she wants to preserve Maryland’s food history, Harris doesn’t want to whitewash the state’s history. The cookbooks “weave the legacy of slave-owning culture into Maryland culture, and some of these cookbooks are so nostalgic,” she says. “The beaten biscuits are a good example. They pretty much relied on slave labor to beat air into the dough for thirty minutes,” she says of unleavened Maryland rolls, and she wants to expose that nostalgia rather than perpetuate it. She’s also written about the fetish Baltimore hotels had in the early 1910s with black chefs who could cook Southern meals, and she sees the longing for “plantation” food pop up in 20th century recipes.

Harris has seen chefs and writers make mistakes or just go with the lore of a recipe, but she’s determined to bring rigor to our understanding of Maryland’s foodways. Even though she is soft-spoken, she has forceful opinions about history and Maryland cuisine, and she’s realized many people are just as passionate.

“At first I took it personally, when people would get really mad,” Harris says, about the way she was approaching a recipe or cooking a certain food. She knew, for example, that readers from Maryland might not agree with her on using all types of crab meat for a Maryland crab cake, since “jumbo lump” cakes are all you see on menus today. “I was trying to be diplomatic and say, ‘I appreciate your passion,’ and eventually that became true. I love how particular people are about their way of doing things.”

In the end, that passion for food and history is what keeps Harris going. She had planned to blog for two years, but there are just so many more recipes to try that she doesn’t see an end in sight yet.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook