Was a May Day Attack by Pilgrims a Practice Run for a Massacre?

One historian of early New England sees the event as a harbinger of deadly violence.

This story was originally published on The Conversation and appears here under a Creative Commons license.

Ever since the ancient Romans decided to honor the agricultural goddess Flora with lewd spectacles in the Circus Maximus, the beginning of May has signaled the coming of spring, a time of revival after a long, dark winter.

In Europe, the holiday—usually celebrated on May 1—became known as May Day. Though traditions varied by country and culture, celebrants often erected maypoles and decorated them with long colorful ribbons. Townspeople, while indulging in food and drink, would frolic for hours. These rituals continue today in parks and on college campuses across the U.S. and Europe.

Throughout history, millions have embraced the holiday—except for the Puritans of early modern England. Though we tend to lump them together, the term “Puritans” included different groups of religious dissenters. Among them were the Pilgrims, who eventually decided to migrate to North America to create new communities according to their religious vision.

It is tempting to attribute the Pilgrims’ hostility toward the holiday to the doom-and-gloom stereotype of the Puritans as humorless and overly pious—the same tendencies that led them to ban Christmas festivities. But their attack on a maypole in Plymouth Colony in 1628 reveals much about their approach toward those who didn’t conform to their vision for the world.

Before they arrived in New England, some Pilgrims must have read the diatribe against May Day penned by a moralist named Philip Stubbs, who lamented the mayhem that erupted in communities across England each year as the holiday approached.

Stubbs described how eager participants would select one of the men among them to be the “Lord of Misrule,” who then led them into pits of debauchery. They would sing and dance in church, much to the consternation of devout ministers. And the participants in these rites always dragged a large tree from a nearby forest to be erected in the town, which became a symbol of their irreligious behavior.

But most in England didn’t see the holiday in such a poor light. For many, these maypoles simply represented raucous, good-natured fun. King James, who reigned from 1603 to 1625, believed that erecting such poles was “harmless” and he castigated Puritans’ efforts to quash the holiday.

In England, Puritans needed to abide by national laws, so there was little they could do to stop the celebrations outside of voicing their disapproval. More effective protests would need to wait.

Once in New England, the Puritans believed they needed to be exemplars of proper Christian behavior. Everyone in their towns had to abide by their rules, and they punished colonists whose actions seemed to undermine devout religious practice.

As the future governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop allegedly declared the Puritans would build their “city on a hill.” Citing language from the Book of Matthew, he claimed that all of the Puritans’ actions would be visible to the entire world, including—most importantly—their God. Any departure from strict obedience to Scripture could threaten their entire mission.

The Pilgrims established their community of Plymouth on the site of the Wampanoag town of Patuxet in 1620. In the years that followed, other English migrants arrived in the region, though many eschewed the Pilgrims’ strict teachings. They came to make money from trading, not escape persecution for their beliefs.

A small group of these colonists moved about 25 miles northwest of Plymouth. A lawyer named Thomas Morton, who had arrived in New England in 1624 or 1625, eventually became the unofficial leader of this camp, which came to be known as Merrymount. In 1628, with Morton’s blessing, the colonists set up an 80-foot maypole crowned with deer antlers in preparation for May Day.

The maypole immediately drew the attention of Plymouth authorities. So did Morton’s antics. According to William Bradford, then the colony’s governor, Morton had become the “Lord of Misrule.” The assembled at Merrymount sang bawdy songs and invited Native American women to join them. The colonists in the small community, the governor wrote, had “revived and celebrated the feasts of the Roman goddess Flora,” which he linked to “the beastly practices of the mad Bacchanalians.” Morton was running, in Bradford’s words, “a School of Atheism.”

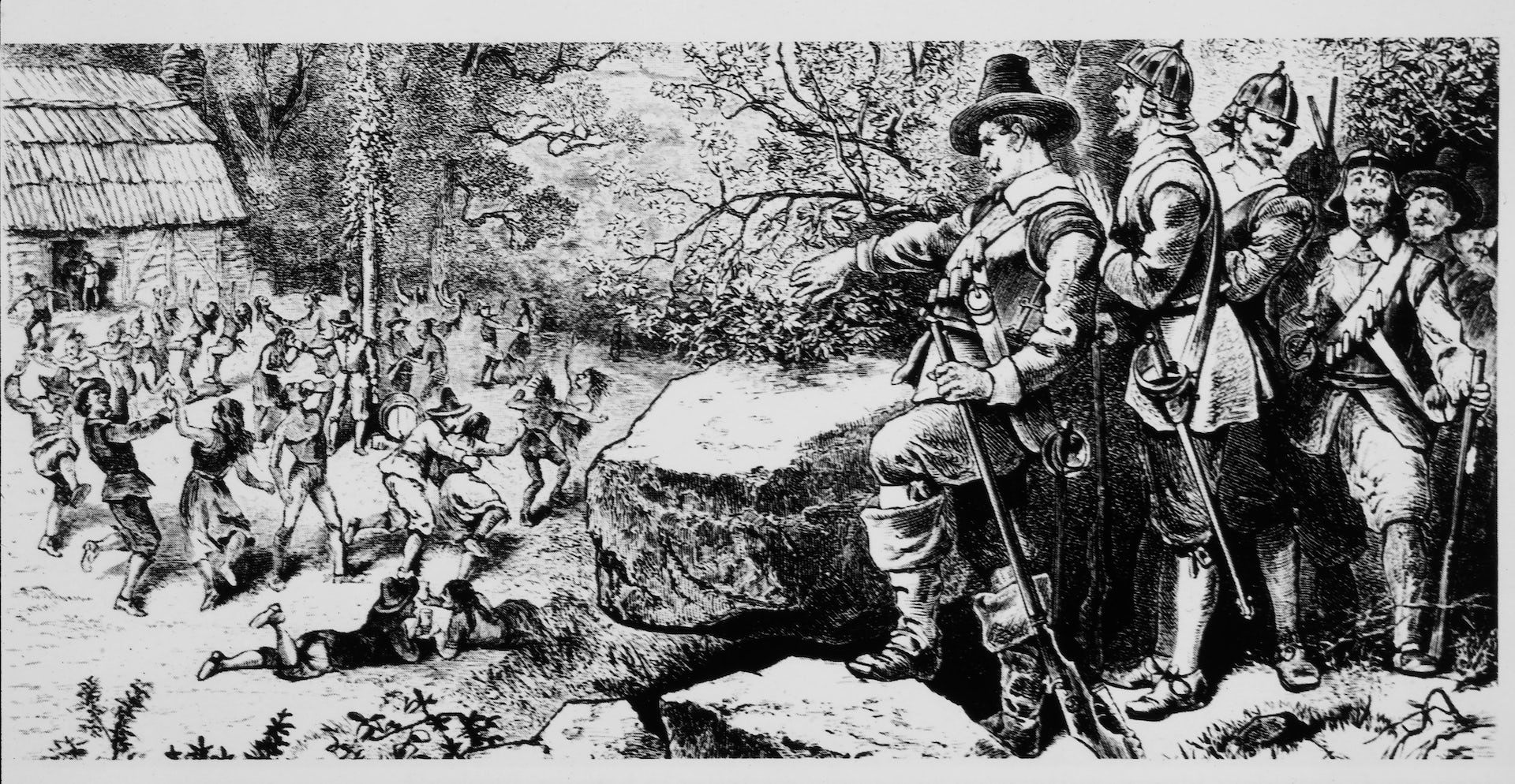

Bradford claimed that Morton and his followers had fallen “to great licentiousness” and led “dissolute” lives. Rather than allow them their fun, the Pilgrims sent a group of armed men to arrest their leader. Soon they exiled Morton back to England.

The next year, John Endecott, a recent immigrant who shared many of the Pilgrims’ beliefs, chopped down the maypole, much to Bradford’s satisfaction.

Why, one might ask, would it matter that stern Puritans would want to quash a good-natured holiday? After all, given many of their other actions, felling a tall tree topped with deer antlers hardly seems worth mentioning.

But as a historian of early New England, I see Bradford’s condemnation of Morton and the destruction of the maypole as a harbinger of future violence. When they chopped down the maypole, the Puritans believed that they were cleansing the landscape, making it more suitable for pious colonists to occupy. It was their way of demonstrating that they could live up their ideals.

Since they believed in predestination, the conviction that everything that occurs is part of a divine plan, they must have figured that God had sent Morton to test them. By exiling him and destroying the maypole, they confirmed what they saw as the righteousness of their cause.

A decade later, with tensions rising between colonists and Indigenous people, the Pilgrims of Plymouth, along with the Puritans of Massachusetts, saw themselves confronting a new test. This time the threat came not from a maypole, but instead from a Native American community that seemed, as Bradford wrote—using language that echoed his condemnation of Morton—“proud and insulting.”

The consequences in 1637 were far worse than at Merrymount. The colonists set a Pequot town aflame and shot those who tried to escape. Historians estimate that at least 400 Native Americans lost their lives in a single night.

Like other English colonizers, the Pilgrims believed they needed to displace Native Americans to create their own communities. But before they did so, they had to get their own houses in order. They could not tolerate any who crossed them, attacking those deemed a threat.

Colonial leaders like Winthrop and Bradford believed any sign of disobedience had to be punished. Clearing Merrymount of its maypole was a dress rehearsal for what was to come.

Peter C. Mancall is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook