Meet the Mettigel, Germany’s Hedgehog Sculpted From Meat

Now a cult-favorite party food, hedgehog-shaped snacks have a long history in Europe.

Some people bake cakes for festive occasions; others put out chips and dip. Leonie Schreiber, a 33-year-old copywriter and designer from Cologne, takes about a pound of uncooked, lightly seasoned ground pork, forms the meat into an oblong shape and sticks it all over with onion slices until it’s covered in “spines.” A couple of olives, capers, or peppercorns for eyes and a nose, and the illusion is complete.

That’s right: it wouldn’t be a German party without a Mettigel, or “meat hedgehog.”

Igel is the German word for Erinaceus europaeus, the spiny, insectivorous nocturnal mammal commonly spotted in gardens across Western Europe. Mett is basically pork tartare, a traditional German delicacy that’s typically smeared on bread rolls for breakfast or as a drinking snack. Around the mid-1900s, the two fused into a pungent pink monstrosity that, thanks to millennials like Schreiber—better known by her Instagram handle, “Mettfluencer”—is still thriving today.

The history of hedgehog-shaped foods goes as far back as the Middle Ages, when royal chefs prepared fanciful display dishes, or “subtleties,” to amuse banquet guests. The 15th-century British manuscript Harleian 279 contains a recipe for a mock hedgehog (known in Middle English as yrchoun) made from an almond-studded pig’s stomach; a French dish from the same era uses the stomach of a sheep. When Württemberg court chef Maister Hannsen penned the foundational German cookbook Maister Hannsen des von Wirtenberg Koch in 1460, he found it important to include not one but three dessert hedgehogs: one of marzipan, one of spiced grated ginger, and one of figs, with almonds or cloves for spines.

A cooked veal liver hedgehog appears in a German encyclopedia some three centuries later. But according to Munich-based author and culinary historian Peter Peter, the Mettigel didn’t assume its current form until the end of World War II and the rapid economic recovery known as the Wirtschaftswunder.

“The Nazis’ ideology was that food was simply nutrition,” Peter says. “It couldn’t be fancy or interesting, because people were going hungry. The ‘correct’ dish at the time was the eintopf [stew]. It made you full, but there was no happiness in it. And then in the ’50s and ’60s, Germans got richer and more kinds of food became available.” Meat shortages during the Nazi era had led cookbook authors to promote “vegetarian solutions.” After the war, Peter says, “the attitude was, ‘Well, now we have meat, and we’ll show it.’”

At the same time, he says, German housewives were spending less time in the kitchen and more time entertaining. Dinner gatherings were no longer formal sit-down affairs, but American-style “parties” with a buffet of cold dishes. As a party food, Mettigel checked all the boxes: “It’s fun, it goes great with beer, men like it because it has a lot of meat, and it’s easy to make. All you have to do is decide if you’re using onions or pretzel sticks for the spines.”

Curiously, cookbooks from that era contain recipes for cheese, egg and pickle hedgehogs, but none involving raw pork. By the time the first instructions for making a Mettigel appeared in the 1980s, the dish had “already fallen out of fashion,” Peter says.

In fact, the spread of bovine spongiform encephalopathy, aka “mad cow” disease, nearly drove the Mettigel, and Mett in general, to extinction. “For a while in the ’90s, eating any kind of raw meat became a big issue,” says chef Sven Jahn, whose biergarten Jäger & Lustig is one of the few Berlin restaurants currently serving Mett (Hackepeter, in the local parlance). “Everyone thought, Oh no, I’ll get sick, but eventually beef tartare started making a comeback, in a more refined form.”

Mett, however, remained taboo, and not only because of health concerns. A new culinary consciousness was emerging in Germany post-reunification, and while steak tartare could be seen as French and cosmopolitan, a smiling, misshapen lump of uncooked pig meat was the ultimate symbol of, in the words of influential food writer Wolfram Siebeck, “das urdeutsche Lust am Dreckfressen”: the deeply German desire to eat garbage.

It’s exactly that crudeness, though, that led to the Mettigel’s comeback. In an article for Jetzt magazine, journalist Nadja Schlüter traces the Mett joke back to 1995, when a man named Edwin confessed on a popular radio call-in show that he regularly purchased 60 kilos of ground pork from his butcher, sculpted it into the shape of a woman and… well, yeah. But Mett humor only really took off once the internet embraced it in the early 2010s, just as the United States was discovering the comedic potential of bacon.

Similar to bacon, Mett is, as Schlüter puts it, “raw, coarse, fatty, ugly—the antithesis of the Instagram aesthetic.” Unlike bacon, it’s also very German, “as subtle and elegant as a half-naked, sunburned white man wearing socks with sandals.”

Above all, Mett is “extremely pun-friendly.” And so hip young German startups began celebrating Mettwoch— a play on Mittwoch, the word for Wednesday—by bringing in the pork spread once a week, in hedgehog form or otherwise. In 2011, a pair of Hamburg colleagues (who sadly declined to be interviewed for this article) spun the tradition into the now-defunct viral website “Museum of Modern Mett,” showcasing such meaty creations as “Kermett the Frog”, a devil-horned fist representing “Heavy Mett-al”, and a game of “Mettris.”

Jürgen Naesert, owner of a second-generation butcher shop in former East Berlin, still remembers the day a TV crew asked him to make “Mett Damon.” “I’d made the Mettigel lots of times, of course, but never that kind of 3-D sculpture. I thought to myself, ach, just do it.” For a 2013 segment on the late-night show Neoparadise, he recreated the Bourne star in pork, complete with real eyes (from a pig), real teeth (from a dental lab), and onions atop his head. “With that white hair, I thought he looked rather like Boris Becker.”

Naesert received plenty of custom Mett requests after that, including a Mercedes logo for a retiring executive at the car company. But these days, he prefers to stick to hedgehogs, filling about two orders for the creature per week while focusing his creativity on developing new types of sausage. “Ground meat is great, but there are limits to what you can do with it. And it’s also a bit played out.”

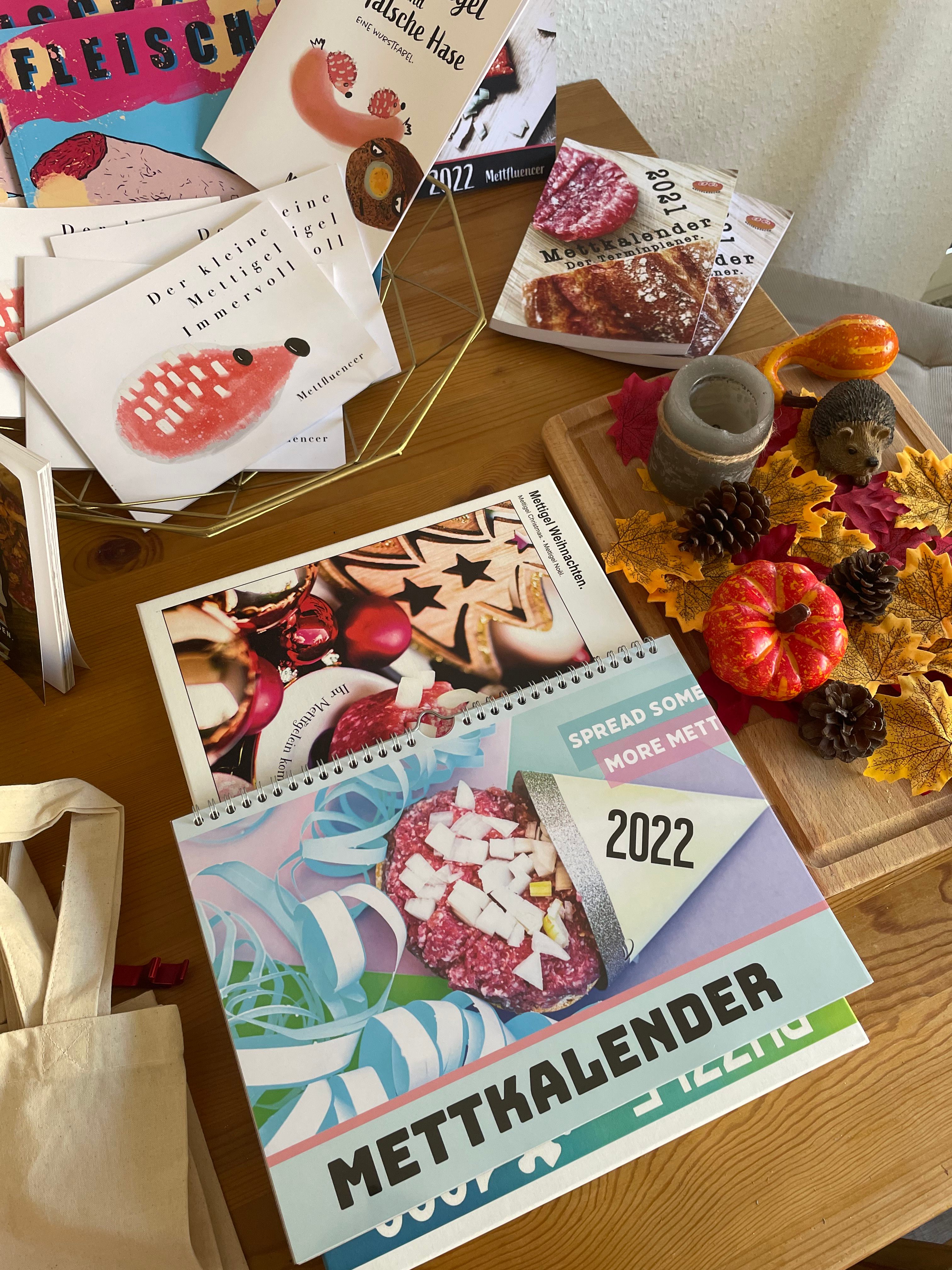

The Mettfluencer would disagree. Four years ago, Schreiber ordered the wrong size of tote bag for a crafting project. Rather than send the too-small bags back, she impulsively decorated them with the inscription “Für mein Mettbrötchen” (“for my Mett sandwich”).

“It really was exactly the right size,” says Schreiber, a Mett lover since trying it at Cologne’s traditional brewpubs in her early twenties. Her friends got a kick out of the bags, and before long raw pork had become her side hustle, with a line of merch ranging from T-shirts to calendars to a children’s book parody titled The Very Full Mettigel. Her customers are her age or younger, and “funnily enough, a lot of them are women. I always thought it was a male-dominated scene.”

Though veganism is on the rise among young Germans (there’s a meatless Mettigel recipe that calls for tomato paste and rice cakes), Schreiber says she’s received little pushback from the animal-free crowd. “I get more complaints from meat lovers saying my photos don’t have enough onions in them.” Besides, she points out, Mett and sustainability aren’t mutually exclusive.

“I’d call it a quite conscious approach to meat. Because it’s raw, you can immediately tell if it isn’t fresh. You don’t buy it at the supermarket; you get it from a butcher you trust, or you go to a local farm … some of the ones in my region even have vending machines where they sell Mett between the milk and the eggs. And when you make a Mettigel, that’s something special. You’re not using the meat in a wasteful way; you’re appreciating it.”

Both Jahn the chef and Naesert the butcher agree that only fresh, high-quality pork should be used for Mett. Trichinosis, that bogeyman of raw pork consumption, has all but been eradicated in most of Europe and the U.S., but negligent handling or improper cooling can open the door for all sorts of other bacteria and parasites. By German law, Mett must be served on the same day that it’s ground. “That’s why we have dishes like Buletten [pork meatballs] on the menu, so that I can cook any leftovers,” Jahn says. Not that there are many: His modernized, tartare-like version of the dish, introduced in 2019, is a hit among biergarten guests.

According to Naesert, the “cooling chain” is key. From the time it’s ground to the time you eat it, the pork must stay below 6 degrees Celsius (43 Fahrenheit). “To be safe, you should serve your Mettigel on ice,” he says. “In the winter, you might be able to leave it out for a few hours. In summer? Definitely not.” It’s for that reason that Mett Damon, having spent a full day hanging around on set, met his end in a trash can.

It may still be a risky dish. Raw pork has been the culprit in numerous salmonella outbreaks. But it’s a risk party hosts are willing to take for a dish that “makes people happy,” as Schreiber says. While most Teutonic fare is cooked and served with a stereotypical lack of frills, the Mettigel, peeking at you cheerfully from atop the table, is a reminder that the German proverb “One doesn’t play with food” is not strictly true. You could say the meaty hedgehog fulfills the same role as its medieval ancestors: that of a festive banquet centerpiece whose purpose isn’t merely to sate hunger but to inspire childish delight. Even if that delight is mixed with irony nowadays, Germany’s love for the dish remains more genuine than many might like to ad-Mett.

Mettigel

Jürgen Naesert of Fleischerei Naesert (“It’s more like a guideline.”)

Ingredients

- 1 pound freshly ground pork shoulder (preferably regional/organic), chilled

- 1 teaspoon salt

- ¼ teaspoon white pepper

- ½ finely diced onion (optional)

- 1 clove minced garlic (optional)

- Pinch of ground caraway seed (optional)

- Other add-ins of your choosing ( “Let your fantasies run wild,” Naesert says.)

- Strips of white onion or pretzel sticks (to serve as the spikes)

- Olives, capers, peppercorns, or allspice berries (to serve as the eyes/nose)

- A torn piece of bay leaf (to serve as the nose/mouth)

Instructions

-

Mix the pork, salt, pepper, and—if using—the spices. Form most of the pork mix into an oval, reserving a smaller amount for the “snout." Decorate as desired.

- Serve on a plate over a tray of ice, with bread rolls, more onions and mustard on the side.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook