Why Rustic Hamlets Host Some of Japan’s Most Striking Modern Architecture

Nostalgia, tourism, and a desire for relevance help drive the trend.

Japanese architecture generally brings to mind one of two images: hypermodern structures that fill crowded metropolises or serene wooden buildings tucked away in placid rural settings. For some remote areas of Japan, however, these architectural worlds collide with bold, modern designs flung deep into the countryside. Perhaps best known among them is Yusuhara, population 3,400, which features hotels, museums, and public buildings from famed architect Kengo Kuma, designer of Tokyo’s striking new National Stadium, built for the 2020/2021 Summer Olympics.

The unassuming town of Yusuhara is 525 miles south of Tokyo, in Kochi Prefecture, on the island of Shikoku. The town itself is not unusual for a rural Japanese municipality. It features lush mountainous scenery—over 90 percent of the town is forested—and modest industry.

It is part of a broader pattern in Japan of sleek, stylish structures finding homes far from the big cities. According to Japanese architectural expert and Kengo Kuma contemporary Azby Brown, “There is a notion among town leaders that ‘We need something that will get noticed, that we can be proud of,’ and architecturally striking buildings are a proven way to do that.”

Standing out conspicuously among more typical rural architectural fare there is the wood-and-glass Yusuhara Town Hall, an unusually stylish building for the world of Japanese officialdom. Indeed, the town office is known to turn heads from visiting bureaucrats. “When I meet staff from other cities, they say, ‘It’s great to work in such an elegant building,’” says a spokesperson for Yusuhara’s Planning and Finance Division in an email. Officials from outside Yusuhara are particularly taken with the office’s ubiquitous wood scent.

A folk-tale-inspired annex to a city-owned hotel and market, complete with a richly thatched exterior, as well as a nearby museum, are other notable Kuma-designed buildings in the town, which itself is billed as a “living museum” to the architect’s works.

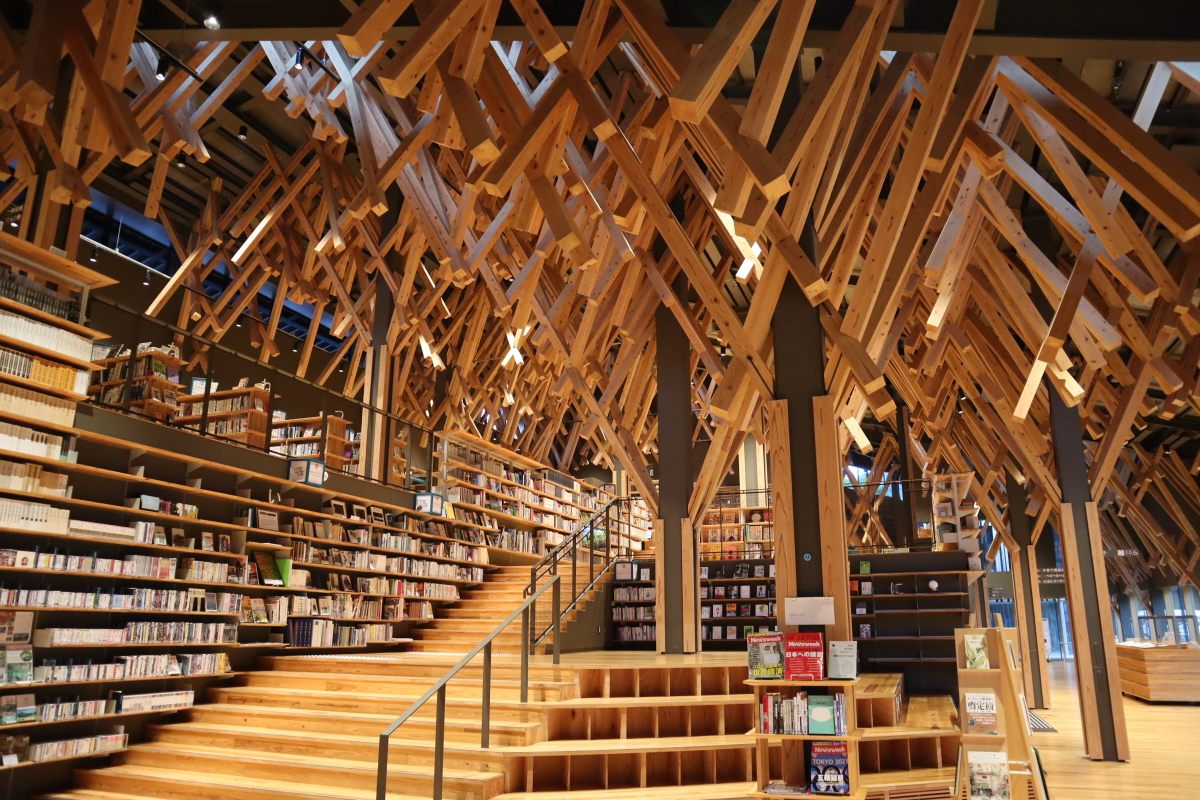

Perhaps most striking of these structures is the Yusuhara Community Library. In line with the municipality’s nickname, the “Town Above the Clouds,” the library is known as Kumonoue no toshokan— the “Library Above the Clouds.” With nearly 21,000 square feet of interior floor space and 35,000 books in its open stacks, it was built with a number of locally sourced timbers, and even features an on-site bouldering wall.

How does a sleepy, otherwise unremarkable town in rural Japan snag the services of a world-renowned architect? The town’s spokesperson explains: “Yusuhara-za was the catalyst for the connection between Kengo Kuma and the town.” Yusuhara-za is a wooden structure, built in 1948 as part of the town’s postwar reconstruction efforts, and the only remaining wooden theater in Kochi Prefecture. Over the years, it has played host to plays, Kabuki performances, and movie screenings, and its conservation in 1995 spurred a movement to construct similar wooden structures.

According to Kuma, in a video produced by the town’s museum dedicated to his work, he visited in 1992 as a junior architect at the urging of a colleague who had been involved in the conservation of Yusuhara-za. He was immediately taken by the town’s “secret garden” atmosphere. This initial visit eventually resulted in a total of six buildings on five sites, designed and built between 1994 and 2018.

But Yusuhara is not the only remote locale in Japan with seemingly incongruous modern architecture. It’s something of a trend. Dotted across the countryside are examples of striking designs one might expect to find in ritzy corners of Tokyo or Osaka. According to architectural expert Brown, in the heyday of Japan’s bubble economy and beyond, “a lot of government money became available for infrastructure like museums and libraries, and there were quite a few projects in out of the way, small towns that were eye-opening.”

Naoshima, a small spit of an island on Japan’s Seto Inland Sea, hosts numerous museums, luxury accommodations, and homes designed by architect Tadao Ando and various artists. The brainchild of Benesse Holdings—best known for its Berlitz travel guides—the collection features the Chichu Art Museum, built largely underground in 2004 to preserve the surrounding natural scenery, and visible only as a collection of geometric shapes from above.

About two hours northwest of Tokyo, the mountain town of Karuizawa in Nagano Prefecture hosts its own array of architectural wonders. A dozen sleek, elegant homes are scattered across the landscape, all designed by preeminent Japanese architects as country escapes for well-heeled clients, including the Imperial Family. Polygon House, a “quasi-Brutalist geode of distressed steel and glass” and the Hoshino Wedding Chapel—no right angles, according to The New York Times—are two examples in this hilly town of just 20,000.

In Kanna-machi—a mountain hamlet where more than half of the residents are 70 or older and Japan’s second-oldest town—a 15,000-square-foot glass-and-steel gymnasium sits on the grounds of its sole junior high school, for use by students and the community. Designed by architects Studio Nasca, this structure, like those in Yusuhara, uses locally sourced wood and complements the adjacent auxiliary town hall, both built as part of the merging of two villages in 2003.

Numerous elements drive the desire to place sleek modern structures in sleepy rural towns. “All of these towns want their story to be heard and there’s a realization that architecture can help them do that,” says Brown. “People value that their history and their story is embodied in these buildings.” Brown also cited the shift away from Japan’s somewhat unsentimental postwar attitude toward older buildings in favor of a greater recognition of the historical and cultural value of preserving those structures.

Traditional cultural factors also play a role. The concept of one’s rustic ancestral home in the countryside still holds a nostalgic allure among the Japanese, even as remote regions lose residents to big cities. Modern structures in remote places are like the inverse of a traditional park in an urban setting—both serve as a bridges between those worlds.

There is also a practical consideration at play: Many of these designs drive local tourism. The architecture of Naoshima, for example, brings in more than 800,000 tourists each year. In Kanna-machi, the modern town office and gymnasium/community center were designed to attract and retain younger residents. “[Towns] feel the need to do something big and new to try to keep young people,” says Brown, “to reassure them that they’re not missing out on the best of contemporary life.”

Yusuhara’s spokesperson also cites the town’s unique wooden buildings as a driver of tourism. “Thanks to Mr. Kuma mentioning Yusuhara in interviews, many people from all over the country … and overseas visited us,” says the spokesperson.

Japan’s major cities offer no shortage of stunning modern architecture, but its unassuming countryside increasingly holds its own, bursting with hidden architectural gems.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook