A Murderous Gravestone Grudge Carved a New Law Into Stone

When murder won’t rest in peace.

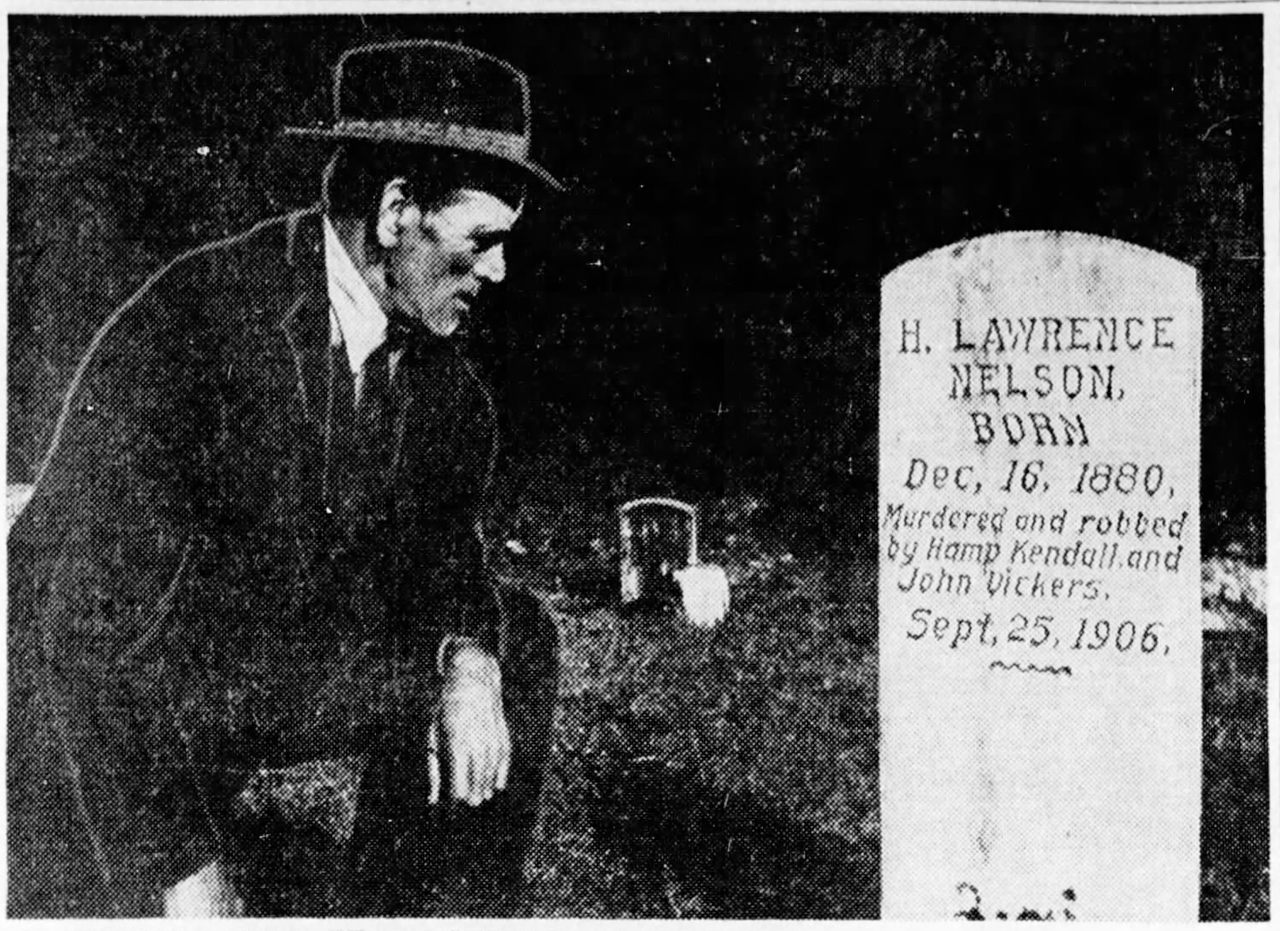

Up a gravel road running behind the Nelson’s Chapel church in Lenoir, North Carolina, sits a small cemetery. For about 50 years, one of the stones, marking the grave of twenty-five-year-old Lawrence Nelson, had a remarkable inscription beneath his name: “Murdered and robbed by Hamp Kendall and John Vickers, Sept. 25, 1906.” It’s not every day that a tombstone accuses people of murder.

Hamp Kendall and John Vickers had initially been imprisoned for Nelson’s killing—but it turns out both men were proven innocent. After their 1907 convictions, a fight followed over the next few decades about the men involved, the murder itself, and the accusatory epitaph that attempted to seal the blame in stone.

It turns out words carved onto a tombstone do matter. The fight surrounding this gravestone and the repercussions that followed have echoed far beyond the grave—and into the legal system today.

It all started in 1906, when young Lawrence Nelson, member of a prominent family, went missing. A few months later, someone came across the body. Charles Hampton “Hamp” Kendall, a local barber’s assistant, and a man named John Vickers had both shared a roominghouse with Nelson.

At the 1907 trial, the chief witness against Kendall and Vickers was a 14-year-old girl named Omah Grier (variously spelled). “Grier claimed that she and her friend, Maggie Lewis, had been paid by Kendall and Vickers to lure Nelson to a designated spot in the woods,” wrote Meghan Cousino, Executive Director of the National Registry of Exonerations Foundation, on the registry’s website. She then said that while the young women were fleeing, they heard gunshots. Kendall took the stand to deny his involvement, but both he and Vickers were convicted of second-degree murder and received sentences of thirty and twenty-six years, respectively.

Lawrence’s father, the Rev. John Hugh Nelson, who ran the church where his son was buried, had the gravestone inscribed with the accusation shortly thereafter. “Most cemeteries would not allow that,” says Tanya Marsh, a law professor at Wake Forest Law School, North Carolina and co-author of the legal text Cemetery Law—whether or not it was considered legal at the time. The Rev. Nelson likely had a “conflict of interest,” Marsh says, since being both the father of the victim and the owner of the graveyard added an extra complication to what was allowed on the gravestone. The reverend died in 1915.

Then in 1917, Governor Thomas Walter Bickett granted pardons to Kendall and Vickers, expressing grave doubt of their guilt. Omah Grier, he said, was an unreliable witness. Other eyewitness testimony contradicted Grier’s, and the girl’s mother had confided to the governor that Grier had admitted lying at the trial.

“The case against Kendall relied substantially on false testimony from Omah Grier,” Cousino explains in an email. “More than a hundred years later, perjury and false accusations continue to be leading contributing factors in wrongful convictions. Unlike forensic science and criminal procedure, which have evolved significantly since Kendall’s 1907 conviction, the power of false testimony remains very similar today in its ability to persuade a jury.”

Soon afterwards, Grier’s cousin Sam Green—who had also been tried for Nelson’s killing but was acquitted—confessed to having murdered Nelson. Then Green took his own life. Vickers died soon after his release from prison. This left Kendall, despite his pardon, to face the stigma of the gravestone alone.

Christine Horton, a longtime Caldwell County resident who knew Kendall as an old man, says the accusatory gravestone “worried him to death.” Kendall showed the gravestone to journalists and tried to get local authorities to remove the inscription. However, the church and local authorities said that effacing the words would violate North Carolina’s law against grave desecration. The stone remained unchanged.

Marsh says North Carolina’s anti-desecration law “includes interfering with the gravestone.” But in this instance, Marsh says the case is more about grave defamation than desecration. “Sounds like people were just trying to shut him down,” she adds, though she stresses that she was not present for the historical case.

Kendall continued to fight the case. In 1947, the state legislature passed North Carolina’s first-ever state law for compensating the wrongfully convicted, a development which newspapers at the time credited to the efforts of Kendall’s allies. Kendall was granted $4,912.56 as compensation for his false conviction.

Then in 1949, the North Carolina legislature passed another major law also inspired by Kendall’s case. In its current version, the law states:

“It shall be illegal for any person to erect or cause to be erected any gravestone or monument bearing any inscription charging any person with the commission of a crime, and it shall be illegal for any person owning, controlling or operating any cemetery to permit such gravestone to be erected and maintained therein. If such gravestone has been erected in any graveyard, cemetery or burial plot, it shall be the duty of the person having charge thereof to remove and obliterate such inscription.”

There was some delay before the Nelson’s Chapel cemetery complied with this statute, but around 1951 or 1952, an unknown person removed the denunciatory gravestone. Though it’s unclear what became of the original, today the current gravestone simply says, beneath Nelson’s name, “Gone to rest.”

To this day, criminal accusations are still not allowed on tombstones in North Carolina, though Marsh says it’s very rare for cases like this to come up in the United States. She teaches the only law school course in the country that focuses on funeral and cemetery law, and in her many years in graveyards, she’s never come across another accusatory epitaph. However, the North Carolina law that resulted from the Nelson gravestone is just state-wide, not national.

A similar accusatory gravestone was more recently seen in Florida. In the early 2000s, a few years before his death in 2011, a man named Herman Harband erected a grave monument for himself. On it, he accused his wife of poisoning him, along with other misdeeds, though no proof of the accusations had ever been offered. The only other information on record is that Herman Harband was arrested in 2000 in New York for pouring a caustic substance on protesters near his apartment and allegedly injuring some police in the process. The man actually ended up later being buried in North Carolina, and his wife had the Florida cemetery take down the gravestone.

Florida doesn’t have any laws specifically against accusatory tombstones, though any such gravestone in the country could face another issue today.

“Laws concerning the written accusation of crimes equally apply to tombstones as other media forms, emphasizing the universal applicability of defamation and libel laws regardless of the platform or context.” writes Nicholas Kassatly, a funeral home negligence lawyer in Florida, in an email. Those guilty of libel, publishing a damaging falsehood against another person, can be charged with large fines or even jail time. “Erecting gravestones with defamatory messages could potentially lead to legal exposure under libel laws, particularly for those who commission or maintain them.”

Accusing gravestones are not a common occurrence in the U.S., and that might be for more reasons than just etiquette. “The rules governing cemeteries themselves often prevent using language that could be seen as offensive or instigative, regardless of specific legal statutes,” Kassatly writes.

In any case, there could be repercussions for those involved in defamatory gravestones, whether it be the tombstone owners, families, or graveyard owners. And words written on stone can be difficult to change, as seen in Kendall’s case. Overall, it’s probably better to let grudges rest in peace.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook