The Nazi Board Games of World War II

These relics of wartime propaganda and anti-Semitism were designed for playtime.

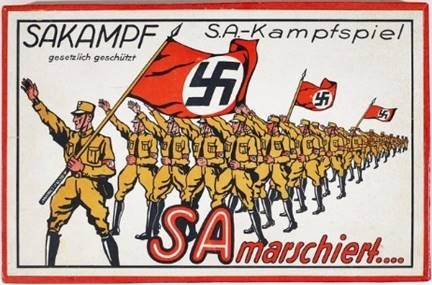

During World War II, the Nazis fueled children’s enthusiasm for both their war effort and genocide partly by stocking toy stores with cheerful-looking but insidious board games. As budding potential members of the Hitler Youth rolled dice, they competed with miniature weaponry to conquer Allied lands and clear gaming boards of pieces depicting caricatures of helpless or greedy Jews. After the war, German families tossed out the incriminating games in untold numbers, but in the last few years dozens have surfaced in institutional collections and on the market.

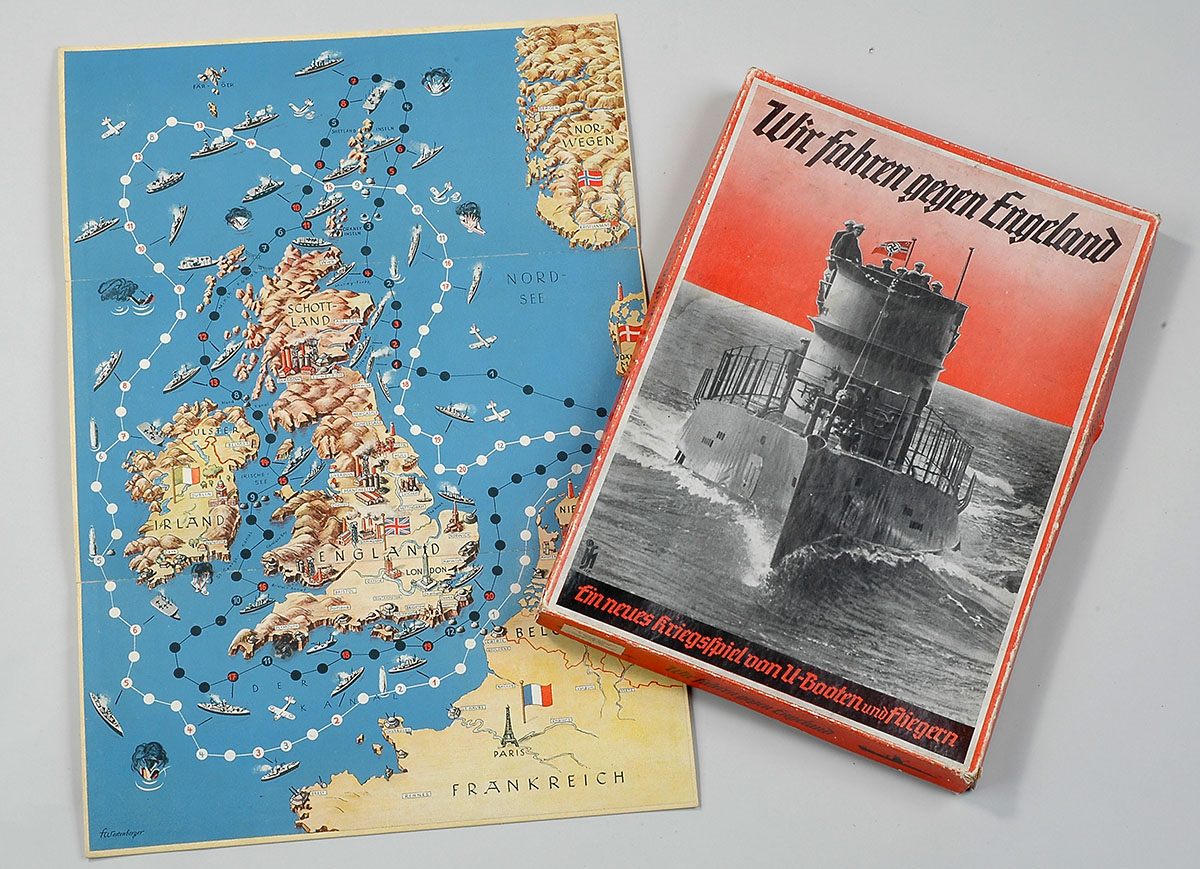

At the International Museum of World War II in Natick, Massachusetts, swastikas line the path to the central victory zone on a swastika-shaped pachisi-style board made in wartime Germany. On another propaganda game in the collection, children could play at encircling the British coastline with tiny U-boats.

Kenneth Rendell, the museum’s founder, says that Nazi power derived partly from such shrewd product design. Manufacturers applied symbols of anti-Semitism and death to toys, along with all manner of other household furnishings, from Christmas ornaments to lightbulb filaments. The racist objects, even if they never directly incited heinous acts, would have inured the owners to the prospect of violence all around them.

“The real power of evil,” Rendell says, “is to make it normal.”

The Wolfsonian museum in Miami Beach has obtained Nazi games with graphics that show masses of soldiers saluting Hitler and gunners bringing down Allied planes. Nazi board games at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., allowed players to imagine themselves as paratroopers sneaking behind enemy lines and radio operators who blocked Allied broadcasts.

Steven Luckert, a senior program curator at the Holocaust Memorial Museum, says that inculcating youth was particularly important for the Nazis—their vision, after all, was that tomorrow belonged to the next generations.

The museum recently acquired a collection of anti-Semitic material produced in Europe and America over the 500 years preceding World War II, and it includes ancestors of the Nazi toys. In 19th-century board games, for example, players tried to avoid giving money to Jews. Numbering nearly 1,000 items, the collection was assembled by Peter Ehrenthal, a Holocaust survivor from Romania who long ran a Manhattan gallery specializing in Judaica. Ehrenthal’s son Michael says the games echo racist ideologies that were common in children’s books of their time. But three-dimensional toys that youngsters held in their hands for hours, he adds, would have been “more tactile to the anti-Semite’s burgeoning mind.”

In the last decade, Regency-Superior auction house, based in St. Louis, Missouri, has sold examples of the Nazi games (for prices between a few hundred and a few thousand dollars each). The boards depict soldiers hugging their sweethearts, burning down villages, and rounding up Jews. Toys related to civilian life illustrate how to behave during and after air raids, by extinguishing fires on apartment window curtains, helping stabilize bombed buildings, and calmly playing board games while waiting for all-clear signals in air-raid shelters.

The auction catalogs quote the games’ unnerving instruction booklets, which explain that they were designed “for spiritual training, military training, and public education.” The author of a booklet for a game about bringing down Allied warplanes asserts that the plaything’s “deeper meaning lies, in the ever-alert mind, the protection of the homeland.”

Thomas Garcia, an antiques dealer in Los Angeles, has spent more than a decade building a collection of Nazi games. He has a few dozen, including a batch that turned up in a German couple’s attic. “The owners themselves were absolutely appalled that they had these things,” he says, and no one could remember who had piled them there. (He has consigned many of his duplicates to Regency-Superior auctions.)

Garcia says that the games’ troubling graphics and messages are important to preserve and document, given their impact. He has also sought out propaganda toys made in Allied countries, which were likewise meant to mold patriots, sometimes with graphics that demonize German and Japanese forces.

As the war dragged on, Garcia says, signs of paranoia and pessimism became more common on German playing boards. They warned about the dangers of double agents and air raids, rather than celebrating enemy nations falling under Axis control. The quality of the materials also deteriorated. By 1942, manufacturers had begun supplying cheap paper playing pieces instead of ones made of metal or plastic. The games, Garcia says, “became very flimsy toward the end—you can tell how the fate of Germany was proceeding.”

Kerstin Merkel, an art historian in Germany, analyzed the subject for a comprehensive book she cowrote, Playing With the Reich: Nazis Ideas in Toys and Children’s Books. Though hardly any records from the manufacturers survive, she says, she found examples to study in museum collections. The objects may have survived postwar purges of propaganda because owners felt sentimental and may “have not seen any political dimension in the toys.” Families may have just nostalgically tucked away these artifacts from the days when—in the form of little zeppelins, torpedoes, Luftwaffe planes, Panzer tanks, and imprisoned Jews—evil was just normal.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook