Before Thanksgiving, There Were the Feasts of ‘The Order of the Good Cheer’

North America’s first culinary social club was born in the 17th-century Canadian frontier.

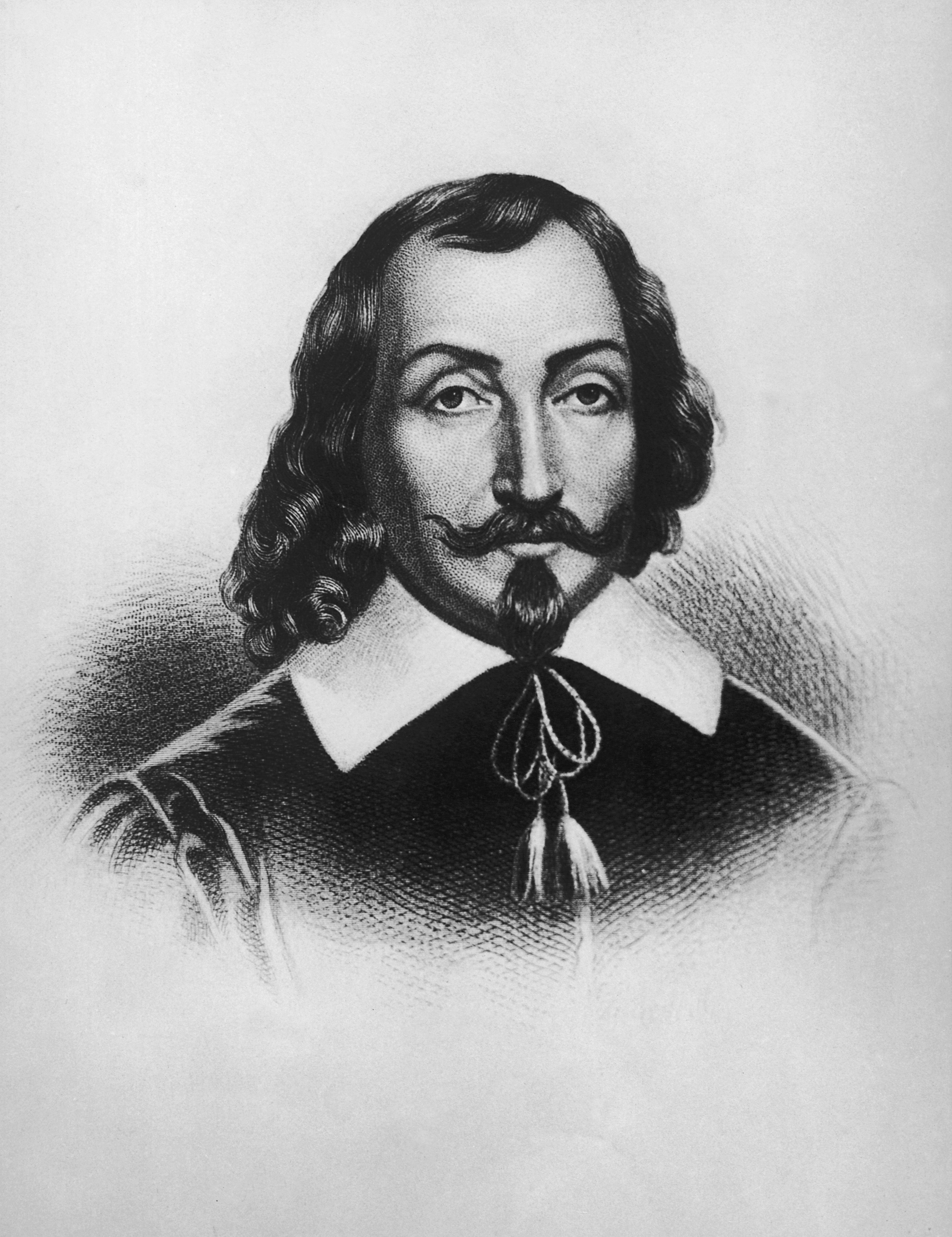

Four centuries ago, the settlers of a small French outpost perched on the north bank of what’s now Nova Scotia’s Annapolis River came up with the novel idea of founding an organization that would not only feed its members, but also uplift spirits during the long and brutally cold winter. Led by cartographer Samuel de Champlain, the Order of Good Cheer, or l’Ordre du Bon-Temps, went on to become what’s considered America’s first social club, not to mention an inspiration for the country’s Thanksgiving celebrations that would follow.

The Order of Good Cheer featured epic feasts that took place weekly in Port-Royal, the then-capital of Acadia, a colony of New France, over the winter of 1606–07. This communal gathering aimed to satisfy settlers’ bodies and minds with gourmet dishes, as well as entertainment, laughter, and all-around revelry.

“Food was obviously an imminent requirement to keep settlers nourished,” says Paul Lalonde, chief interpreter at the Port-Royal National Historic Site, a living history museum and reconstruction of the French habitation at its original location. “But with the Order of Good Cheer, Champlain also looked at what kinds of other elements could sustain them.” What he and the Order’s other organizers came up with was a rousing success when it came to raising morale.

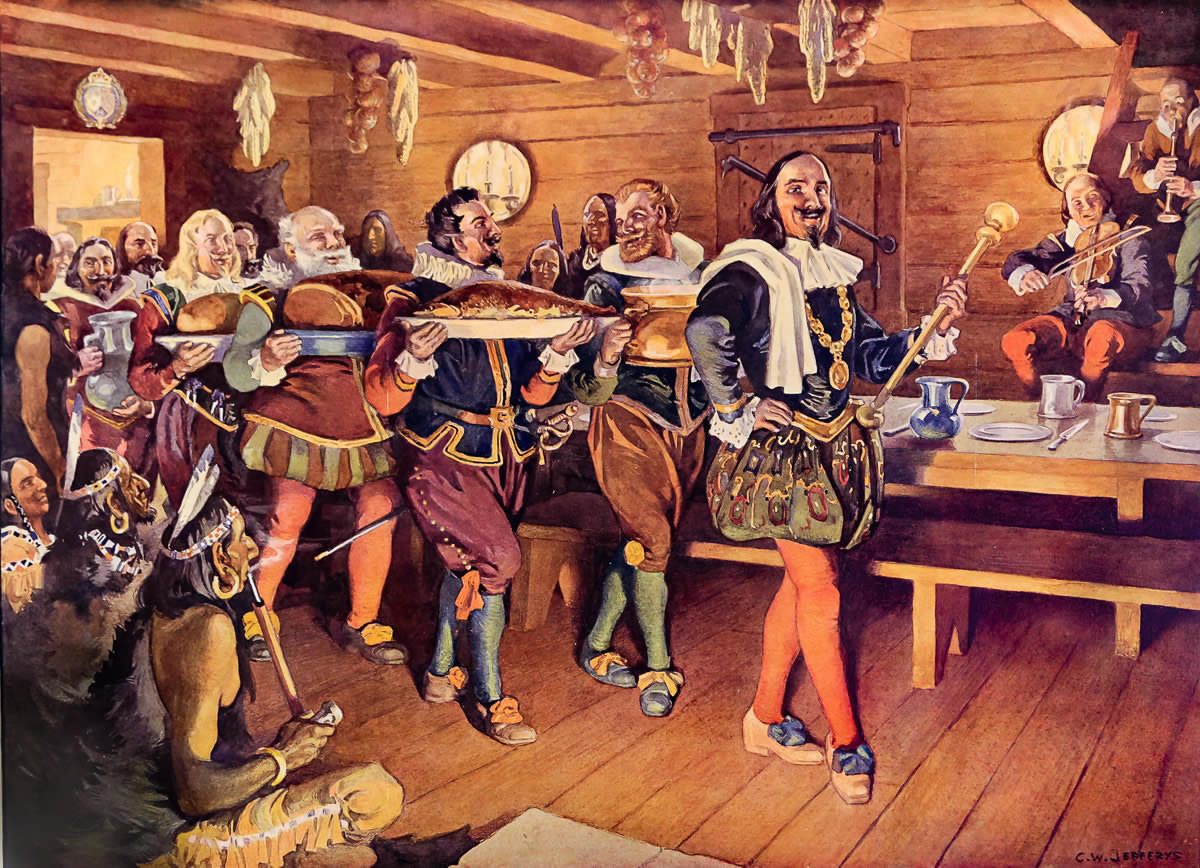

The club’s main focus was a recurring banquet that featured approximately 15 dishes—delicacies like roasted beaver tail (“It’s filled with meat,” says Lalonde, “but you have to scrape away the outer scale”), and moose muffle stew, a bizarre-sounding dish that includes the animal’s upper lip and nostrils, but is said to be both rich and nutritious. Typically, the men finished off their meal with cups of hippocras, a type of warm spiced wine, while the evening’s entertainment included everything from speeches and dancing to music and plays.

It all started a year earlier, when Port-Royal’s settlers had endured a disastrous winter on nearby Saint Croix Island. There was unusually severe weather, a shortage of fresh drinking water, and an absence of fresh fruit and vegetables. Thirty-five of St. Croix’s 79 settlers ultimately perished. While many of them died from scurvy, others suffered from exposure and malnutrition. Rather than face such extreme casualties another year, the settlement’s leader—French explorer and trader Pierre Dugua de Mons—asked his cartographer to find a more suitable place for an outpost. Champlain chose a sheltered location across the Bay of Fundy, one with ample farmland and a reliable water source. They named it Port-Royal.

This time, however, the men weren’t taking any chances with idleness (which many people at the time believed was a cause of scurvy, since lethargy and fatigue were early symptoms) or poor eating, hosting their first Order of Good Cheer feast on November 14, 1606. Its purpose: to celebrate the return of Baron de Poutrincourt, Point-Royal’s governor, to the outpost following a coastal expedition, while also keeping the settlers well-fed, optimistic, and upbeat. “It was the 15 or so ‘gentlemen’ of the settlement,” a 17th-century term for a person of slightly higher social rank, like a landowner or a surgeon, says Lalonde. These “gentlemen,” Lalonde adds, “sat at the table with Poutrincourt and were in charge of planning the evening.”

The outpost’s 35 other settlers (all men) participated from the sidelines, dining at outlying tables and clapping and cheering as the late afternoon/early evening festivities unfolded. Indigenous men, women, and children, many of whom had been instrumental in teaching the settlers how to survive such an unfamiliar landscape, watched this “welcoming home” of Poutrincourt as well, snacking on bits of rye bread that had been handed out for the event.

“The settlers definitely made an occasion out of it,” says Lalonde. “They were doing their best to bring a bubble of French society to their little outpost, and recreate the comforts of home.” Their “Chief Banquet,” as the weekly dinner was known, included cuts of fowl and game such as geese, partridge, caribou, and otter that they’d hunted, as well as ingredients such as prunes, dry cod, butter, and oil that came from their shipping provisions. These already lavish menu items were enlivened with the likes of cinnamon, cloves, thyme, and chervil. As a bit of pomp and circumstance, the men discharged muskets celebrating Poutrincourt’s safe return at the inaugural feast, and there was even the performance of a dramatic play: poet and gentleman settler Marc Lescarbot’s Théâtre de Neptune, which is credited today as North America’s first-ever theater production.

This recurring banquet quickly became Port-Royal’s most anticipated event that winter. A rotating “Chief Steward” presided over and organized that particular week’s festivities, from the menu to the evening entertainment. They’d kick things off by leading a procession from the kitchen into the dining room, with a napkin draped over their shoulder, a staff of office in hand, and—dangling from their neck—the collar of the Order (a chain of office brought with them from France) on full display. The other Order members would then follow, each one carrying a separate dish and circling the table as they went. After offering grace for the meal, the chief steward would then hand over his collar to the next “steward” in line, they’d toast each other with wine, and then the celebratory feast would begin.

Occasionally, Mi’kmaq chiefs Membertou and Messamoet would even join them at the table to eat, a thank-you from the settlers’ for the First Nation peoples’ roles as guides and trading partners. In fact, in many ways, the Order of Good Cheer had all the makings of what might have been Canada’s inaugural Thanksgiving meal.

But while the country’s Thanksgiving holiday (which is celebrated in October) is more tied to the annual harvest, Lalonde believes there’s a natural link between Canada’s Thanksgiving and the Order of Good Cheer. It “taps into something that’s universally human,” he says. “The proverbial ‘breaking of bread’ together. In the case of the Order, it was the coming European and Indigenous people, sharing the bounty with the aim of helping each other get through the winter.”

Indeed, the winter of 1606–1607 proved much easier on the settlers than the previous one, and by all accounts the Order of Good Cheer was a rousing success. That May, however, de Monts’s trading privileges in the New World were officially revoked, forcing the settlers to return to France. Not only did they abandon Port-Royal, but they also left their beloved social club behind.

Still, this doesn’t mean that the Order of Good Cheer was forgotten. Over the years there’ve been numerous efforts to revive various aspects of the group. Jo Marie Powers, a now-retired professor at the University of Guelph’s Lang’s School of Hospitality, Food and Tourism Management, led one such project.

“It’s just really a way of having a good time,” says Powers. “Or, having a ‘good cheer,’ which means party.” Powers spent several decades researching the club and its traditions, culminating in a CBC radio documentary on the Order as well as her own chief banquet. Powers set up several tables in her home, then invited her friends to bring a historic dish, potluck-style, from a menu she’d gathered featuring recipes reminiscent of what may have been served in the 17th century. There were items like cranberry marmalade, quenelles of cod with lobster sauce, venison pie, and a prune and marzipan tart with sabayon, a light custard.

One of Powers’s favorite dishes of the evening was éclade de moules. “It’s mussels cooked under pine needles,” she says, “in the same way that fishermen in southwestern France would prepare them along the shore.” The dish involves arranging mussels in the shape of a cross on a wet pine board, then taking them outdoors, covering them in dry pine needles, and lighting the needles on fire for a deliciously smoky flavor. There was also music, dancing, and speeches from the professor, as well as some of her friends. “I really think it was the best party I think I’ve ever given,” says Powers.

Since 2001, Tourism Nova Scotia has been offering certificates of honorary Order of Good Cheer membership at various offices throughout the province. The only requirements for joining are adhering to four requests: having a good time while visiting, remembering Nova Scotia fondly, speaking about the country kindly, and promising to return.

Lalonde says that the Port-Royal National Historic site occasionally recreates some 17th-century foods. These might include “digby chicken” (actually smoked herring) and hodge podge, a one-pot soup of whatever fresh seasonal ingredients are available. But, at the moment, there’s no set annual feast.

This doesn’t mean a revival of the innovative social club is completely out of the cards. “We have a holiday every month in Canada,” says Powers, “except for February. I always thought, Wouldn’t an annual Order of Good Cheer be nice?”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook