The Battle to Bottle Palm Wine

It’s delicious, cherished, and difficult to commercialize. These entrepreneurs are bringing it to the United States.

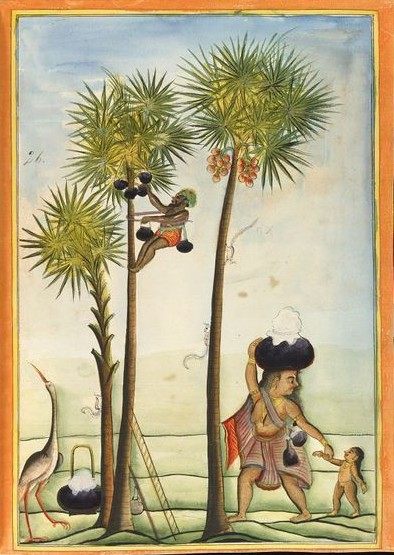

It’s a common sight in tropical places from Nigeria to India to the Philippines. In the mornings, before the harsh sun has burned the mist away, tappers climb the palm trees. Aided with nothing more than wiry muscles and woven rope or cloth, they scale to the top, risking the steep drop to collect palm sap. Like tropical maple-syrup collectors, they pierce the tree and tie earthen pots to catch the juice that seeps out of this wound. As these pots fill over the course of the day, natural yeast and bacteria from the air will work their magic on the sap, transforming the thin, sugary, slightly coconutty nectar into lightly fizzy, sweet-and-sour, milky white booze. This is palm wine.

Onye Ahanotu, an artist and materials engineer turned food scientist, grew up hearing about the importance of palm wine, but rarely sampled the drink itself. His parents immigrated from Southeast Nigeria to the Napa Valley in California. “An area that wasn’t populated by a lot of Nigerians,” Ahanotu says. Food—especially his favorite dish, okra soup—was his most powerful connection to his family’s heritage.

In the stories he heard about Nigeria, palm wine enjoyed a pride of place. Hopeful spouses presented it to their in-laws as part of marriage traditions; weddings weren’t complete without it. “I understood it to be a cornerstone of culture and society,” says Ahanotu. There was only one problem: Ahanotu’s family couldn’t get palm wine in the United States.

If you hunt hard enough, you can find the odd bottle of imported palm wine, such as Ghana’s Nkulenu brand, in a few specialty stores in the United States. But the beverage hasn’t been widely distributed, and even in countries where it is produced, such as Nigeria and India, efforts to commercialize it remain smaller scale.

The lack of palm wine in U.S. markets is partly due to lack of demand. Palm-based alcohol is culturally important to many West African, South Asian, and Southeast Asian groups, but isn’t mainstream in Euro-American cuisines. But it’s also technical, a question of labor, process, and supply. Palm wine is a naturally occurring alcohol, produced as ambient yeast and bacteria, encouraged by hot and moist tropical air, feast on the sugars in palm sap. “It spontaneously forms whenever there is damage to the palm tree,” says Ahanotu. Because of this rapid fermentation, palm wine is difficult to stabilize, and turns to vinegar within a few days of tapping. While in some regions, such as the Philippines and the Indian state of Goa, palm vinegar is used for cooking, it’s less preferred in West Africa and most of South Asia.

As a result, palm-wine production has remained largely a hyper-local, village- or cottage-level industry, in which individual tappers or small tappers’ unions forge relationships with local families and restaurants. There’s also an environmental barrier to palm-wine commercialization: While many producers simply tap the sap from the tree, some cut down the tree entirely, draining the sap from its heart. That makes widespread palm-wine production a potentially resource-intense prospect.

Producers have long attempted to commercialize palm wine for export. As far back as 1975, for example, the New York Times reported on the Ghana Industrial Holding Company’s eventually failed attempt to develop a palm wine for U.S. distribution. But these efforts never stuck.

That’s a problem for members of the Nigerian diaspora, like Ahanotu, whose family is left to celebrate weddings with beer or grape wine instead. South Indian-Americans such as Hemant Kishore, a chef from Kerala who now lives in Las Vegas, also feel the absence. In South India, palm wine, called toddy, is a workingman’s beverage. It’s sold out of small, roadside and riverside restaurants, called toddy shops, which are dive bars famous for spicy, meat-and-seafood-rich menus—duck, frog legs, beef, and pork—and the sweet-and-sour brew.

Kishore, a pastry chef by training, imported the concept to Las Vegas in 2016, when he was searching for commercial kitchen space for his lunch-delivery business. A local dive bar agreed to rent him space for cheap. The only caveat: Kishore had to make bar food for customers. “They just wanted some kind of bar snacks for people who came to play slot machines,” he says. His impromptu toddy shop was a success, and he now runs it as a regular pop-up. Yet while he can reproduce the food, Kishore doesn’t have access to palm wine itself. He looked into palm wine production in Mexico, where locals have been enjoying the drink ever since Spanish ships introduced coconut palms from the Philippines in the late 1500s, but didn’t have the resources to import it or produce his own.

In 2018, inspired by experiences like Kishore’s and his own, Ahanotu founded Ikenga Wines. The company is his trailblazing attempt at high-tech palm wine production, and he’s aiming to be the first to commercialize the process for distribution in the United States. Ahanotu has already begun hosting palm-wine tastings and offering advanced orders to U.S. consumers, with a promise of delivering lightly aged, effervescent wines within eight to 12 months. If he succeeds, he could be the first to produce palm wine commercially in the United States—though he’ll be competing with entrepreneur Daniella Ekwueme, a Nigerian palm wine producer who is eyeing the U.S. market.

To solve the fermentation challenges around palm wine, Ahanotu is drawing on his background as an artist and materials engineer. As a scientist, he seeks to understand natural processes and materials, and harness them for sustainable development. He’s helped engineer slippery surfaces to prevent mussels from attaching to ships and created structural bricks based on origami. As an artist, he produced a multimedia installation highlighting hidden green space in Oakland, and created a photo series depicting the immediacy and vibrancy of life in contemporary Nigeria. He titled the series “Afro-presentism,” a focus on contemporary African life that riffs on “Afro-futurism,” an aesthetic that combines African diasporic culture with high technology.

His approach to commercializing palm wine is futuristic. In fact, he’s not using palm sap at all. Rather than figure out a way to extract, preserve, and import the sap to the United States—a prospect he says would be less environmentally sustainable and risk souring—he’s working out of a biotech incubation space in the Bay to create a liquid combination of sugars. It’s designed to be molecularly identical to palm sap, though more stable.

The more stable base allows Ahanotu to focus on what he argues is the true essence of palm wine: fermentation. “Palm wine is spontaneously produced, so the terroir is the microbes in the air that happen to land in there,” he says. While Ahanotu is controlling the fermentation process in the lab, he sourced the yeast and microbes straight from Nigeria. In 2018, driven by curiosity about his family roots and palm wine, he traveled through Southeast Nigeria, visiting family, tasting palm wines, and even working with producers to deliver wine and sample the sap from specific trees, including those on his family’s property.

Ahanotu returned to California with tiny vials of liquid gold: microbe-rich samples of five different local palm wines. He’s been working in the lab to isolate the different microbes, including yeast and Lactobacillaceae bacteria, that lend each their unique flavor profile. Then, he applies these microbes to his signature “sap,” controlling the fermentation to produce sparkling brews that attempt to capture distinctive regional flavor notes. Whereas wine made from natural sap sours quickly, Ahanotu’s process allows for aging, thus potentially creating more layered flavors.

When I express skepticism—can a product rightly be called palm wine without palm sap?—he compares his process to diamond fabrication. “You can mine a diamond, you can spend all this money, and you can ship it across the world. Or you can fabricate a diamond through temperature and physics,” he says. “In my mind, it’s definitely still palm.”

Ahanotu won’t tell me exactly how he’s engineered the “secret sauce” of his manufactured sap, or how it will lead to a palm-wine-like flavor. So I turn to Theodore N’Dede Djeni, a researcher in food biotechnology and microbiology at the Université d’Abobo-Adjamé who has published work on the chemical composition of palm wine. (Djeni is not involved in Ikenga Wines’ efforts). Djeni and his team have identified 338 separate compounds that make up palm wine, both found in the original sap and as a product of fermentation. About 100 of these compounds are key to the wine’s flavor, with 50 compounds from yeast alone contributing to the scent.

Djeni says achieving the full flavor profile of naturally fermented palm wine will also be challenging. “The sap is fermented by various microorganisms, and many of these microorganisms remain unknown,” he says. Some are difficult to cultivate in a lab. As a result, Ahanotu’s task is very difficult. “But it’s not impossible.”

Ahanotu isn’t the first to create molecular booze. Producers attempting to engineer other kinds of wine and spirits have faced challenges in reproducing the full complexity of the natural flavor—a taster described one lab-made whiskey as containing notes of “imitation vanilla, schoolyard woodchips, and rubbing alcohol.” Ahanotu, however, claims that his process creates a product with more complexity in flavor than conventionally produced palm wine. Rather than the “generic sweet and sour” of the natural variant, Ahanotu says, his variety is sweet and lightly carbonated, with fruity, tropical notes such as soursop, lychee, and guava.

Ahanotu isn’t the only entrepreneur with his eye on the U.S. market, though he is the most tech-focused. Daniella Ekwueme founded Pamii, arguably Nigeria’s most successful commercial palm wine brand, in 2016, after noticing that the palm wine served at family weddings was always slightly sour. “You can get palm wine fresh in the local villages,” she says. “You can’t actually get fresh tasting palm wine in cities.” If you travel from a village on the outskirts of Lagos to the city center with a keg of palm wine, it spoils before arrival.

Her family had some palm trees, and Ekwueme had some time on summer break from studying in the U.K. “I was like, hey, this would be an interesting summer project to get my head stuck in,” Ekwueme says. Four years later, Ekwueme has managed to do what other local palm-wine bottlers haven’t: commercialize a consistent product that appeals to Nigeria’s huge youth market. Because palm wine is so important in traditional and ceremonial settings, says Ekwueme, most young Nigerians wouldn’t consider it a beverage to sip from a bottle at the beach. “People associate it with drinking palm wine out of a calabash,” or gourd, she says.

Thanks to close collaboration with local tappers, biochemists working out the technical kinks, and a savvy youth marketing campaign, Ekwueme has created a bottled palm wine with mass appeal. Currently, Pamii distributes to small stores and supermarkets, and they’re in the process of setting up their own microbrewery in Lagos. By late this year, they’re hoping to begin export to the United States.

In contrast to Ahanotu’s high-tech, more wine-like brew, Pamii is light and breezy, a cool, bubbly alternative to beer on a summer day. The company’s Instagram is full of attractive young people lounging with the signature bottle at parties or on the beach. “We started as light cocktails with our friends,” Ekwueme says. She recommends drinking Pamii alone on a hot day, or as part of a cocktail with brown sugar or sugar cane syrup and something a bit stronger—a smoky liquor she says Pamii also has in the works.

With both Ekwueme and Ahanotu aiming to start selling in the U.S. in the next year, American consumers may soon have multiple palm-wine options to choose from. That’s good news for Chef Hemant Kishore, who says he’d love to bring actual toddy to his pop-up toddy shop. And that’s good news for diasporic people like Ahanotu’s family, whose younger members may finally get to experience traditions in the United States complete with the elusive palm wine they could previously only taste through their parents’ memories.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook