The Transformation of Pamola, the Protector of Mount Katahdin

How a fearsome Penobscot Nation legend became a mascot of outdoor adventure seekers.

The weather at the top of Katahdin–Maine’s tallest mountain at around 5,267 feet, and the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail–is unpredictable even on the most beautiful days. Depending on the season, the conditions above the tree line can change from peaceful sunshine to rolling thunderstorms to treacherous snowstorms within a matter of minutes.

Locals who spent time on the mountain have a simple explanation for the capricious conditions: It’s Pamola, the guardian of Katahdin—or K’taadn, as it is more closely spelled in the language the area’s Indigenous people, the Penobscot Nation of the Wabanaki Confederacy. Centuries of Penobscot legend describe Pamola as hideous and birdlike, with spindly legs, long arms, a sharp beak, and a violent temperament that demands respect for it and the mountain it resides on.

Today, though, the Penboscot’s protective spirit has become an icon for summiters of Katahdin —the very people it once frightened away. More contemporary renderings of Pamola are comparatively Disneyfied from the legends of yore, with a friendly moose face, a (notably buff) man’s torso, and eagle wings. Though the beast retains its connection to the Katahdin community, the Pamola of today is perhaps less often spotted atop the mountain than on beer cans and Boy Scout badges.

Pamola has long existed in the oral tradition of the Penobscot people, but it was first documented in written records by white settlers climbing Katahdin in the early 19th century. (Some evidence exists of European priests living in Maine and white captives of the Wabanaki making earlier reference to a creature that may have been Pamola, though lack of Indigenous language skills probably conflated Pamola and other Penobscot legends.)

Christopher Packard, author of Mythical Creatures of Maine, says that in the first recorded ascent of Katahdin by Charles Turner Jr. in 1804, the Wabanaki members of the party told Turner that Pamola “inhabits ‘Katahdin’ at least in winter, and flies off in the spring with tremendous rumbling noises.” Because of their timing, the crew was able to ascend and return without inciting the spirit’s wrath.

Not all climbers have been so lucky. Henry David Thoreau’s Penobscot guides would not continue with him in his attempted ascent of Katahdin in 1846, explaining that the poor weather conditions indicated Pamola’s fury. Thoreau went on without them but eventually had to turn back, the fog so thick he could barely see in front of him. “Pamola is always angry with those who climb to the summit of K’taadn,” Thoreau wrote in his book The Maine Woods.

![“With proper respect, [Pamola] will allow you to climb to the top" of Mount Katahdin, writes Maria Girouard, a historian, activist, and member of the Penobscot Nation. "Disrespect will get you elsewhere.”](https://img.atlasobscura.com/BOV4batg1SbQlVd_3No4mLnO0Ggpz3ktc_AlsOC6n4k/rt:fill/w:1200/el:1/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy85NDBhOWRjYzNl/NTZiY2FjNjFfMTI3/OTM0NDEyMi1GMjUx/UlAuanBn.jpg)

Maria Girouard*, a historian, activist, and member of the Penobscot Nation, detailed a range of Penobscot tales about Pamola for the Friends of Baxter State Park spring 2021 newsletter, “Forever Wild.” She tells the tale of former Indian Island chief John Neptune, who served from 1816 until his death in 1865, keeping an agitated Pamola out of a cave where he was sleeping in the winter by freezing a rock in its entrance (a story also recorded by famed Maine folklorist Fannie Hardy Eckstrom in her essay “The Katahdin Legends” for the Bulletin of the Appalachian Mountain Club in 1924, though in that telling it was a “shack with a strong door” that kept Pamola out). Girouard also relays the account of a young Penobscot runner in 1989 who climbed Katahdin despite Pamola’s tempestuous warnings and suffered from injuries in the following year as retribution.

“Instead of climbing the sacred mountain, the Wabanaki would only travel to K’taadn to become closer to the spirits that lived in the mountain, but avoided the wrath of the spirit most popular in K’taadn legends—Pamola,” Girouard writes. “With proper respect, it will allow you to climb to the top. Disrespect will get you elsewhere.”

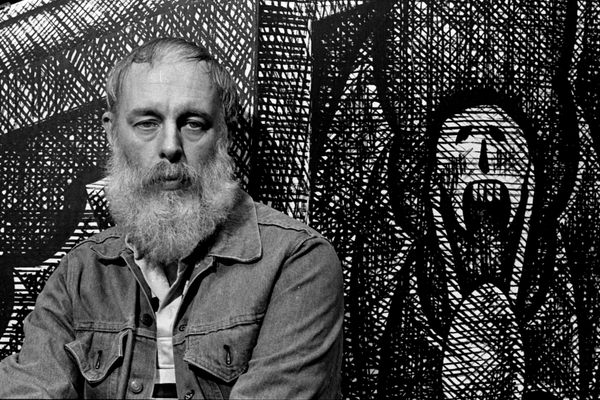

Today in Maine’s outdoor recreation community—about 63 percent of which self-identified as White, according to a report by the Maine Department of Agriculture and Forestry; 0 percent identify as Native American—Pamola is probably best known through the “yarns” spun by famed Katahdin guide Mark Leroy Dudley, who lived at the mountain’s Chimney Pond and guided hikes through the park’s trails from the 1890s until his death in 1942. In Chimney Pond Tales, a compendium of Dudley’s stories published in 1991, Pamola is at once terrifying and silly; he causes thunderstorms, falls ill (and is healed by Dudley), rafts on a stand-up paddleboard made of crowbars, gets married, and joins the storied guide on other misadventures.

Pamola is shown on the cover of Chimney Pond Tales as a giant moose-headed man with aquiline legs and wings, smoking a barrel as a pipe with Dudley by his side on a mountain top. Dudley’s depiction of Pamola is hidden in plain sight around the region, everywhere from the cans of Baxter Brewing Company’s signature brews to badges on Boy Scouts (who also have a lodge on the mountain named for the spirit).

Luke Livingston, founder of Baxter Brewing Co., said that he first heard about Pamola during the company’s original brand development in 2010, when a designer pitched the creature’s likeness for their original logo. The first beer that the company came out with was an American pale ale called Pamola, which featured a lightning-wielding rendering of the creature on the can—Dudley’s version of Pamola, perhaps, but with more of its original menace.

Livingston said that Pamola played such a central role in Baxter Brewing Co.’s original branding because the story “resonated” due to its deep ties to the company’s namesake region and outdoors community, which aligned with Livingston’s goal to make his beer “for everyone that you could get anywhere and take everywhere.” Also, he admitted, Pamola is “badass.” “How could you not be psyched about that as a mascot and a logo?” Livingston says. “It felt a lot like what I wanted the beer to represent.”

Still, Wabanaki knowledge keepers today prefer to keep the most sacred stories about Pamola within the tribe, in part due to a lack of trust towards non-Indigenous communities. Livingston admits that though reception to Pamola in Baxter Brewing Co.’s branding was overwhelmingly positive, he did receive a “one in a million” email from a critical customer saying that the company’s use of Pamola was “disrespectful;” he never heard from the Penobscot tribe directly about it. Baxter Brewing Co. retired the logo in 2019.*

For Packard the lasting influence of Pamola among different groups in the region is itself an indication of the spirit’s power. “The fact that this creature, this being, this spirit has found different ways of staying in our culture is particularly powerful to me,” Packard says. “I’m a strong believer that since people like farmers, guides, lumberjacks, and hunters whose lives depended on their knowledge of this land tell these stories, they at least have some reflection in truth.”

Yes, modern depictions of Pamola miss the mark in some ways. Like many creatures in Wabanaki lore, Pamola has found the ability to change shape and remanifest in ways that aren’t always easy to categorize. “Many creatures in Wabanaki lore can change size and shape. The idea that creatures can change shape and size and the way that they exist in multiple ways is difficult for these early writers and modern people of Western culture to really comprehend,” Packard says. “To try to trap it into that description is completely missing the point of its actual nature.”

*Clarification: This article was updated to note that Baxter Brewing Co. no longer uses the Pamola logo.

*Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled Marie Girouard’s name.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook