Why a 272-Year-Old Philosopher Just Got Carted Across a College Quad

A new home for Jeremy Bentham’s old bones is prompting a philosophical debate.

Jeremy Bentham is not unlike an aging British rock star: The older he gets, the more tours he seems to go on. Sometimes Bentham’s severed, mummified head accompanies the rest of him. Other times it’s kept in a climate-controlled room at University College London for safekeeping. After every trip, until its most recent one, the English philosopher’s remains—most of them, anyway—have been returned to a box within a box in a side corridor at the college.

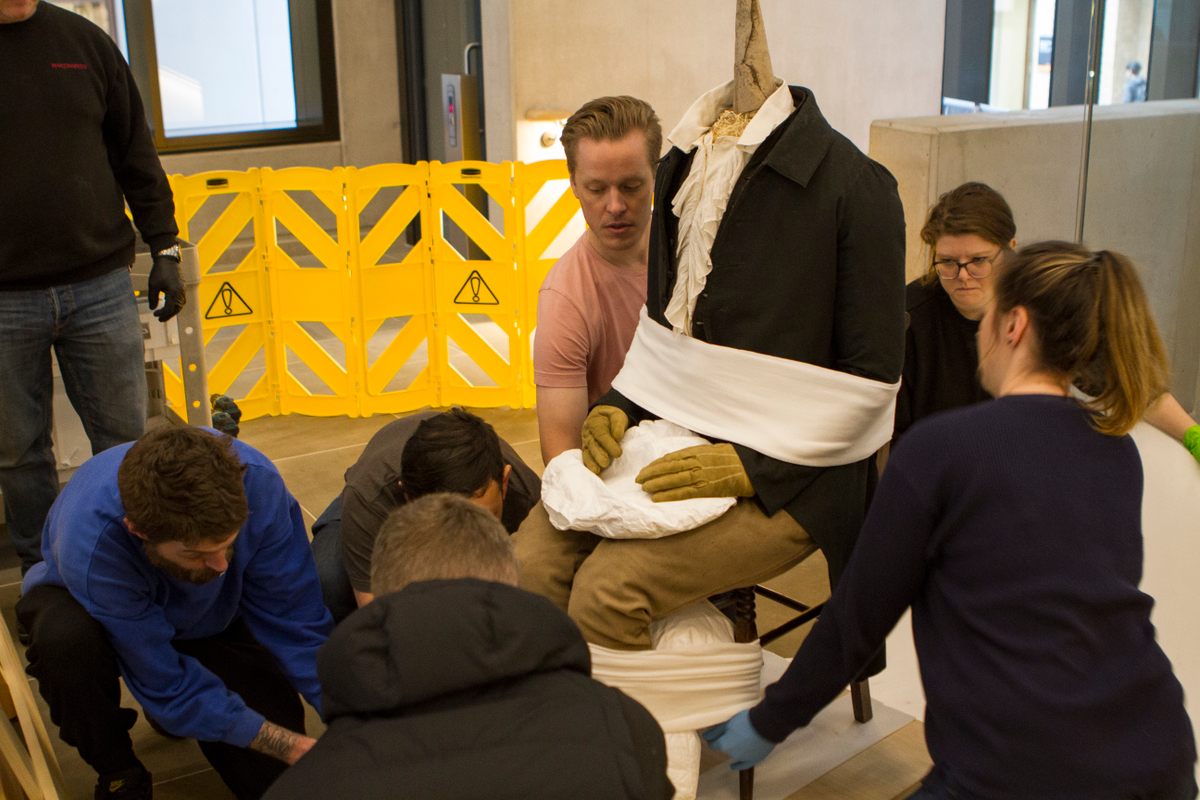

In February, the “auto-icon”—Bentham’s skeleton, cocooned in stuffing and the clothes he wore when he was alive—made one of the shorter, albeit more permanent, moves in its 188-year history. Bentham was deconstructed, removed from the wooden boxes that’ve been home to his remains since World War II, and shepherded into a new glass case in UCL’s new student center.

“At the moment, UCL is in the middle of a big refurbishment program,” says Hannah Cornish, a science curator at UCL who helped supervise the cross-campus commute. “[A]s part of that we had to move the auto-icon. We’ve taken the opportunity to look at the best way to preserve it.”

Since Bentham’s death, in 1832, his auto-icon has traveled across England, Germany, and, just last year, the Atlantic, to New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. But after every trip since it was evacuated from London during the second World War, it’s always returned to the wooden boxes in UCL’s Wilkins Building. Inquisitive students and curious tourists could find the dead philosopher’s wax replacement head gazing beyond them, toward nothing in particular. That same glassy stare persists today, only through a new, modernized container.

“What we were looking for is somewhere we could rely on the light, temperature, and humidity conditions,” Cornish says. “It brings the auto-icon into the center of the student body—and Bentham was a big advocate of education for all, regardless of things like class, race, and gender.”

Bentham’s resurrection as an auto-icon was inscribed in the late philosopher’s will, which requested that a number of fixtures be put in place to preserve his remains, that they be dressed in the clothes he wore in life, and that they occasionally be brought into meetings involving his still-living friends, so that what’s left of Bentham might enjoy their company.

“It’s very hard to describe it to people because there aren’t any other auto-icons,” Cornish says. “[Bentham] thought it’d catch on.”

The auto-icon’s existence is a peculiar addendum to the life of one of England’s most radical philosophers of the 19th century. Bentham was a champion of utilitarianism, which posits that what does the most good for the most people is what’s best. He knew he wanted to donate his body to science after he died, in line with his ethical code—that people should be useful in life and in death. But he also wanted his remains preserved, in part to spite the church, which he frequently criticized.

Due to a combination of bureaucratic mismanagement and crude taxidermy, Bentham’s head became unsuitable for public display—it became too ugly, in other words—and his organs were separated from the rest of his remains. But the skeleton remains the literal backbone of the auto-icon.

The recent bump-up from two wooden boxes to a novel glass case has caused a stir in the UCL community, as students and faculty alike have weighed in on the aesthetic and practical utility of the move. Many have brought up one question: What would Jeremy Bentham do?

“For Bentham, assessing the move of the auto-icon—as indeed for anything else—would be a utility calculation,” says Tim Causer, a senior research associate with the UCL-based Bentham Project, an initiative to produce a new edition of Bentham’s life works and correspondence. “Does the auto-icon’s new location make people happy or not—that would be the only thing that matters.”

This isn’t the first time the auto-icon’s location has drawn criticism. In 1857, when it was just 25 years young, its creator (and Bentham’s longtime friend), the physician Thomas Southwood-Smith, lamented UCL’s placement of the remains.

“No publicity is given to the fact that Bentham reposes there in some back room,” he wrote. “The authorities seem to be afraid or ashamed of their own possession.”

The auto-icon bounced around quite a bit—from Southwood-Smith’s charge to the UCL Anatomy Museum to the UCL Library to Stanstead Bury and back to UCL—but by the 2010s, its longtime mahogany-box home had become a haven for pests like carpet beetles and clothes moths, eager to take a bite out of the early 19th-century garb that clothes the stuffing-encased skeleton. That, combined with the Wilkins Building’s imminent renovations, made now an ideal time to find the auto-icon a new home.

So it was unboxed, dismantled, and shepherded through UCL’s Japanese garden, on a choreographed route to minimize the risk of what Cornish calls “birdstrikes”—pigeons confusing the stuffed person for a privy and defecating on it.

“It was wrapped in plastic, because we [took] the whole thing outside,” Cornish says. “It was a rainy day, so we wanted to make sure Bentham stayed dry.”

Once in the new student center, the auto-icon took the elevator down to its new case, where it was reconstituted in the image of Jeremy Bentham.

Soon afterward, concerns began to proliferate on social media. Some are upset that Bentham isn’t in his original box. (Only one of the older wood boxes—the smaller one—may be original. The larger wooden one dates to the 1940s.) Others have called out discrepancies between the wishes outlined in Bentham’s will and his new case.

Causer, however, notes that these wishes were bungled pretty much from the outset. Nor were the old boxes perfect. “There was a typescript label on the inner wooden box, stating Bentham’s name, dates of birth and decease, and wrongly claiming that Bentham founded UCL,” he says. “I’ve wanted to rip that label off for years, as that’s one of the myths about Bentham that refuses to die.”

Others have expressed concern that the auto-icon is merely on public display, rather than tastefully sequestered until a proper “Bentham commemoration event” comes along.

Treating Bentham’s remains in the manner requested in his will and ensuring that the objects remain preserved in perpetuity is “quite a difficult balance” to strike, Cornish says. “The way we looked at it is that the auto-icon is now a museum object that we’re responsible for. We’ve taken the approach that our duty of care is to preserve this unique object.”

There are also those who feel that the glass casing is too modernist, and is aesthetically dissonant with the traditional trappings of the dead philosopher (one Twitter critic likens the case to a “department store clothing display”).

But Causer says that some of Bentham’s own ideas run counter to this line of thinking. “While I have some sympathy with the view that the relocation seems to go against tradition and doesn’t look right,” she says, “Bentham himself would have had no truck with that argument. In his Book of Fallacies, Bentham discussed what he called the ‘Ancestor-Worshippers’ Fallacy’—that is, the argument that since something had always been done one way, it should always be done that way. Bentham spent most of his life, after all, taking that attitude to task in trying to reform the British establishment.”

One thing is inarguable: Bentham’s new location makes the auto-icon more visible and accessible—the UCL student center is located in the heart of London—and improves the conditions of its preservation.

“The auto-icon is undoubtedly a weird thing,” Causer says, “and Bentham evidently had a sense of high self-regard that he would ask for his body to be preserved in this way. But I would hope that the move might encourage visitors not to dismiss the auto-icon as a macabre curio, the final wish of a strange old man, or something ghoulish or creepy.”

Perhaps, as Bentham hoped, it can be wheeled out for events that he would have enjoyed in life: a good party or a lively debate, its presence spurring conversations about—and perhaps actions toward—the greater good. The move has already sparked discussions about what’s best for the remains themselves.

“People are very fond of the auto-icon,” says Cornish. “We hesitate to call him a mascot, because the auto-icon contains human remains. We treat it with a bit more respect. I hope more people will see him in the student center.”

Currently, the auto-icon sits next to a large panel that describes Bentham and his work in a couple of pithy paragraphs. Cornish says that a booth with more information and context, as well as a touch screen, are on order, and will soon supplement the auto-icon’s new home.

As eerily vacant as that glassy gaze may be, says Causer, Bentham, an atheist, is making a point from beyond the grave, vis-à-vis the auto-icon—his final refutation of religion and life after death.

“Even though to a visitor the auto-icon and its benign waxy smile gives the impression that Bentham is present,” he says, “it is not him any more, and is a reminder that Bentham the human is—like we all will one day become—‘senseless matter.’ And that what matters is to make the most of the life we have, and to promote the greatest happiness during that time.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook