When Lemon-Shaped Juice Containers Set a British Legal Precedent

You know the ones.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Plastic, barring all the environmental problems and health concerns that might come with it, is awesome as a moldable product. It shows up in all sorts of places, from laptop cases, to CDs, to bottles.

It’s also used to hold lemon juice—in containers that, when you think about them, are a bit strange, since most of them are also actually shaped like lemons. These first started appearing decades ago in the post-World War II plastic boom, and haven’t stopped showing up in stores or the back of your refrigerator since.

Last week, in the U.K., where many are sold under the brand name Jif, fans again celebrated what, there, has become the juice containers’ unofficial holiday: Shrove Tuesday (here known as Fat Tuesday or Mardi Gras), when many Brits traditionally make pancakes flavored with a bit of lemon juice.

But back to the lemon-shaped containers: Where, in fact, did they come from? Other fruit juices don’t get their own fruit-shaped containers, after all (except, sure, limes, though for our purposes here we’ll count them in the same family as lemons).

It turns out that the lemon-shaped backstory involves some things you might expect, like a disputed claim of who exactly invented them, but also one thing you probably don’t: a heated and precedent-setting legal battle in Great Britain.

The history of the lemon-shaped plastic container, in other words, is more complicated than you probably think.

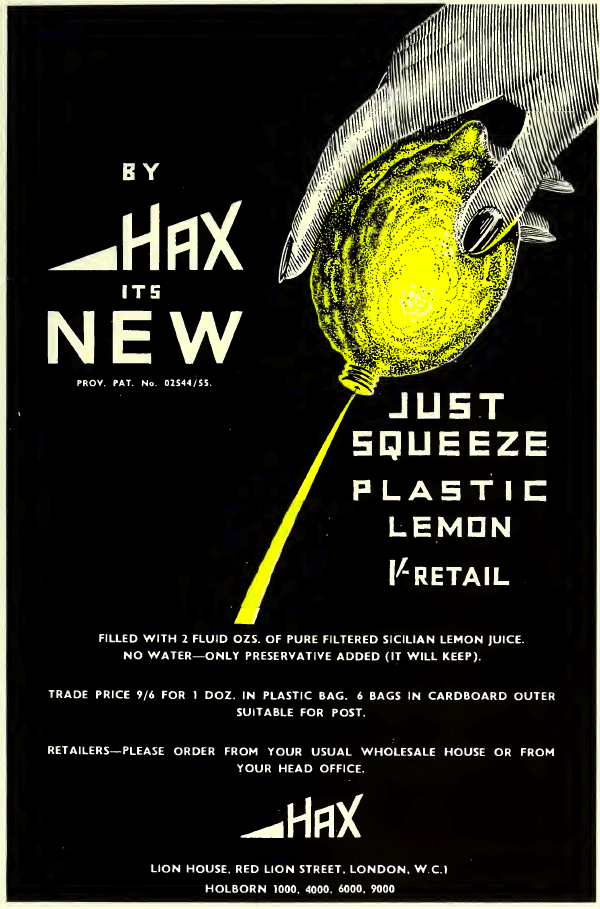

In 1959, the syndicated columnist Alice Hughes, sang the praises of a then-still-novel magical device, which had became common in the United States and the United Kingdom earlier that decade.

“This same lemon juice, contained in glass bottles, has been selling in groceries for years,” Hughes wrote. “Now it has received fresh impetus because a year or two ago some smart container designer persuaded its manufacturers to sell it in lemon-like containers which help justify the claim to real lemon juice.”

In fact, that “smart container designer,” according to the industrial design firm Beach Packaging Design, was a guy named Bill Pugh.

In the years following World War II, Pugh was the chief plastics designer for a company named Cascelloid, which was the only company in the United Kingdom—and one of only two companies in the world at the time—that had a machine that was able to blow plastic bottles into a molded shape.

Pugh built the design at the behest of a British firm, Edward Hack, Ltd., in the 1950s, and a number of American companies quickly copied the idea. (A legal document suggests they originally came from Italy in the post-World War II era, but Pugh is responsible for the modern form.)

According to The Independent, Pugh created a mold out of a combination of wood and lemon peel, recreated that mold with plaster, played with the shape as much as possible, and eventually came up with the perfect form.

This was one of many molded plastic products that Pugh’s team designed in the roughly two decades he worked with Cascelloid. He was an artist of sorts, and his medium was molded plastic.

“He was patient and a perfectionist,” his obituary says. “In similar vein he made amusing plastic fruits, a gaudy tomato-shaped ketchup bottle for cafe tables, and a range of nasal sprays.”

In terms of combining form and function, though, the lemon hit all the bases—beyond its visual appeal, you also only usually need a little lemon juice at a time, meaning that lemon juice required a container that could safely store the juice for long periods of time.

Initially, the juice was sold in the containers under the Hax brand name, but, later, after the product was acquired by the British company Reckitt & Colman (now known as Reckitt Benckiser), and the product’s name was changed to what it’s now sold as: Jif. (Yes, like the peanut butter.)

And, over the years, Jif lemons became hugely popular in the U.K., specifically around Shrove Tuesday, which, according to a 2012 Marketing article, accounts for 71 percent of Jif’s sales for the entire year.

Reckitt & Colman had this market mostly to itself for decades, but by the mid-1980s, perhaps inevitably, competitors came calling, including one in particular, the American company Borden, that would set the stage for a huge legal battle.

The initial challenge came in 1985, when Borden, which was already doing pretty well selling lemon juice under the brand name ReaLemon, saw Jif’s success in the U.K. and decided that it wanted in.

Both companies sold lemon-shaped juice containers, but Borden’s entry into the British market meant that Jif owners Reckitt & Colman could challenge them on legal grounds on their home turf.

A subsequent lawsuit highlighted a problem for Reckitt & Colman: The design of its lemon made its product distinctive in plastic form, but effectively impossible to trademark.

“The purity of this idea, though, exposed the brand to imitation and costly litigation,” brand consultant Silas Amos said in a 2012 Marketing article. “Perhaps adding one ‘twist’ to the lemon design might have turned an obvious idea into a more distinctive (and protectable) brand?”

That, eventually, made Reckitt & Colman Ltd. v Borden Inc, decided by the House of Lords in 1990, an important part of British case law, as it created a test for proving whether a product deserved legal protection despite otherwise being generic—a concept known in British law as “passing off.”

The gist of the three-part test, as formulated by Lord Oliver of Aylmerton:

- There must be an existing reputation that the public carries with the original product or design. (check)

- The competing product creates confusion or misrepresentation in the market, whether intentional or not. (check)

- There are signs that the confusion created by the competing product negatively impacts the bottom line of the original one. (double-check)

Reckitt & Colman easily hit all three parts of this test.

“[A]lthough the common law will protect goodwill against misrepresentation by recognising a monopoly in a particular get-up, it will not recognise a monopoly in the article itself,” Lord Oliver wrote in his legal opinion. “Thus A can compete with B by copying his goods provided that he does not do so in such a way as to suggest that his goods are those of B.”

Borden, then, wasn’t barred from making a plastic lemon that looked like a real one, but they did have to ensure that its design and marketing were distinctive from Jif’s and not simply intended to create market confusion.

Such cases on both sides of the Atlantic are notoriously difficult to win, but Reckitt & Colman had a generation of goodwill and history on its side, even if, in the end, it couldn’t ensure that the lemon-shaped lemon juice container was theirs and theirs only.

You still can’t trademark nature, in other words, even if sometimes your particular squeeze on it is what sets you apart.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook