Recommended Reading: Rob Dunn’s “Every Living Thing”

In the preface to Rob Dunn’s Every Living Thing: Man’s Obsessive Quest to Catalog Life, from Nanobacteria to New Monkeys, E.O. Wilson describes the stories that follow as “personality-based historical narratives.” Just between you and me, I am pretty into personality-based historical narratives. They make the otherwise mundane past burst before you.

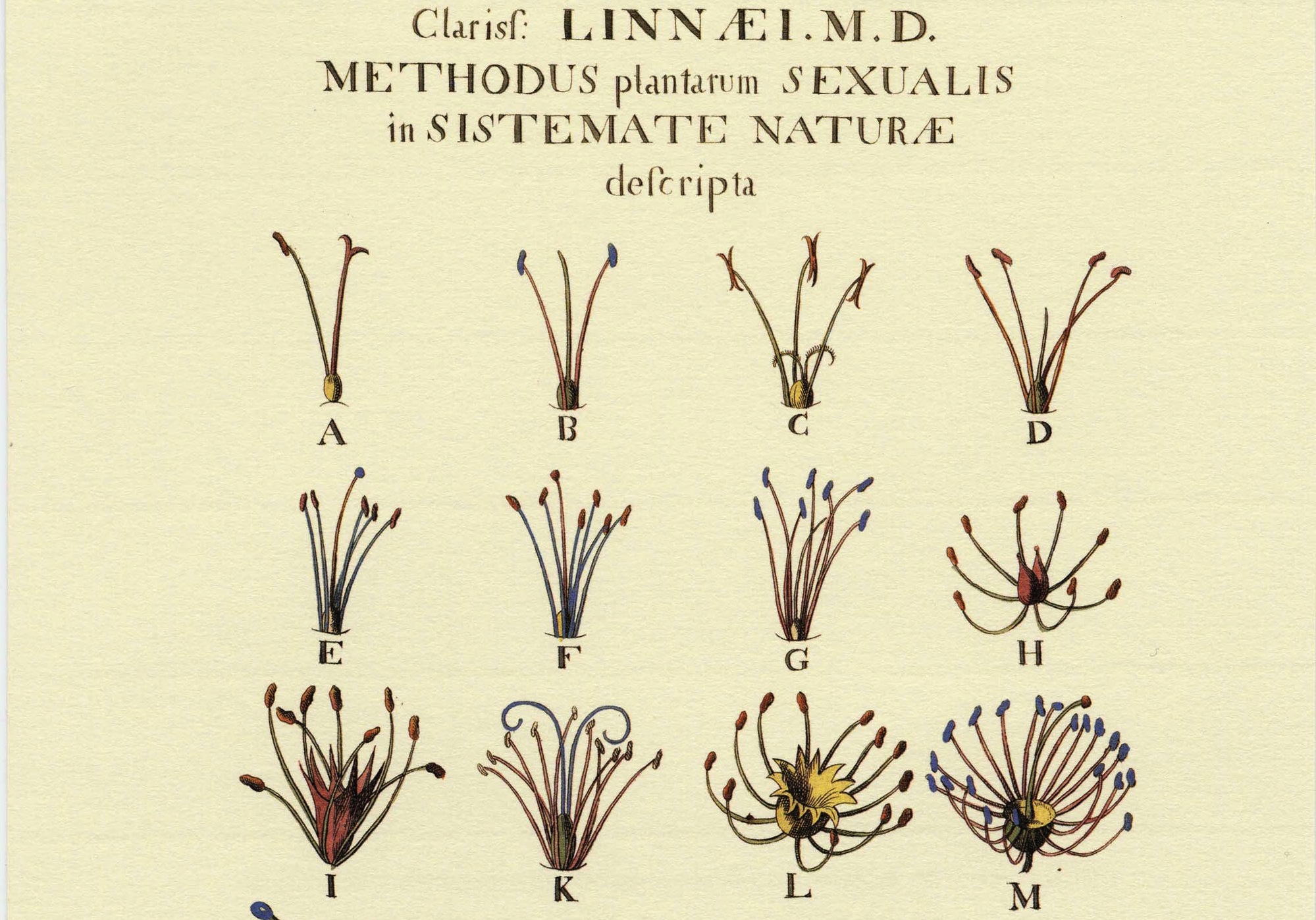

Sure, Carl Linnaeus invented species taxonomy as we have come to know it – but he was also kind of crazy. Dunn brings Linnaeus’ and other lesser known scientists’ lives to light, taking his readers through their life stories to how and where and with what they made their discoveries.

(source)

Every Living Thing isn’t really about science, or it is only incidentally. It is about how we relate to science and the unique characters who’ve spent their lives chasing beetles from trees in Panama and spending the subsequent decades staring at their specimens under microscopes.

Of the many stories that Dunn tells, I was most captivated by Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Bates, biologists who ventured to Brazil in 1848 to find more species. And damn did they! According to Darwin, Bates collected more than 14,000 animals – 8,000 of them new to science – most in his backyard in the Amazon where he lived, more or less by himself, for eleven years. After leaving the Amazon, Wallace traveled to Malaysia where his epiphanies influenced Darwin and the rest of evolutionary theory. In a bout of malarial fever, he dreamt of, as Dunn says, “species changing forms, one bird of paradise changing into dozens, one monkey turning into multiple kinds of monkeys, one primate changing into man.” Wallace then wrote to Bates and other scientists about his realizations. Malarial fever! That’s how we got evolution.

(source)

In the midst of these compelling biographies, Dunn reminds us how small we are, that we are but only a small branch on the sprawling, spindly taxonomic tree – one we don’t really understand. Dunn also navigates the large spectrum of life, focusing on the most plentiful life forms on earth: invertebrates. Bugs, bacteria, even nanobacteria fill the pages.

He says, “As scientists, we are perpetually willing to shine our lights around us, see nothing, and conclude that there is nothing left to see. Our lights are weak, the universe large.” Science, he seems to suggest, is not about knowing but about not-knowing.

(A last nerdy note: The index is really good. It’s hard to find a book that is filled with sentences, not graphs and definitions, with a comprehensive index.)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook