A Photographer’s Guide to Creating Portraits From a Distance

Visual artists are working from home—with help from FaceTime and Zoom.

Bảo Ngô’s photographs are both dreamy and forbidding. In a recent batch of images, a woman in red lounges by an empty pool, tilting her face towards a gloomy sky. There’s no one around to see her floor-length dress or her glamorous blue eyeshadow, which is as bright as the chlorinated water. This isn’t an average photoshoot: The images, which are slightly blurry, are screenshots from FaceTime, the Apple video chat app. This is photography in the time of the coronavirus.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic forced artists around the world to shelter in place, a small number of photographers have started conducting virtual photoshoots using programs such as FaceTime and Zoom. Every photographer has adapted differently. For Ngô, FaceTime photography is a way to preserve the ethos of her in-person work. “My work is very cinema-inspired, so I like to have interesting styling and interesting settings,” she says. “I like my photos to evoke a lot of emotion, and have it all feel like it’s part of a story.”

Ngô came up with the idea of a FaceTime photoshoot during a video chat with her sister, who had a color-changing lamp. “If I have decent lighting and a willing subject, there might still be a way to continue taking photographs,” she thought to herself. The story behind these poolside photos, taken in Los Angeles with assistance from her model, Matilda Sakamoto, and Sakomoto’s mother, feels symptomatic of the times. “It’s an eerie, almost apocalyptic story of a woman who is stuck in this environment she can’t leave,” Ngô says. “It’s just her trying to enjoy her time there.”

Normally, for high-budget photoshoots, Sakamoto says that a stylist, make-up artist, and photographer would prepare for the work behind closed doors, and the model would simply show up. But for this photoshoot, Ngô and Sakamoto were partners: The day before the session, Sakamoto wandered around the apartment complex where she and her mother are sheltering in place, taking photos of potential sets to send to Ngô. The building was deserted, save for a neighbor bringing in some groceries. Later, Sakamoto raided her closet and sent pictures of potential outfits and her eyeshadow palette to Ngô.

From her home in New York, Ngô looked through the pictures and picked out potential locations while styling Sakamoto’s clothes. Sakamoto served as her own makeup artist, opting for a heavy blue eyeshadow look to complement the reds and blues of the background. When it came time for the actual photo-taking, Sakamoto’s mother stepped in to help in lieu of a tripod, holding Sakamoto’s iPhone and listening to Ngô’s live, remote directing. “Shift the frame to the right, just a tiny bit,” Ngô told Sakamoto’s mother. Then, to Sakamoto herself, who was modeling without the cues of a shutter noise, “Lift your chin up. Turn your body to the side.”

“Besides the fact that you’re listening to a phantom voice over the screen, it didn’t feel too crazy,” Sakamoto says. “I thought it was going to be a lot weirder than it was.”

The lighting and backdrop in a remote photoshoot relies heavily on the model’s current surroundings. After all the theaters in New York closed, Jenny Anderson, a Broadway photographer, started taking portraits from a distance. One of the first steps in her process is finding natural light in her subjects’ environments. “Look through your house and see if you can find any interesting light,” she instructs her subjects. Are there any abstract shadows around their home? Is the light pooling in from the window? Is it hitting the floor?

“Most people stand in front of the window, and I‘m like, ‘No, no, no. The light needs to be in front of you,” Anderson says. She doesn’t take her photos as digital screenshots—instead, she points her camera at her own computer screen. If you want to try this at home, Anderson goes on, make sure to turn off any lights that could interfere with the photos on the screen.

Anderson also advises taking many photographs to find the right shot. Some may show the moiré effect, which describes waves that sometimes appear on screens when a camera tries to capture an image of it. “I overshoot,” Anderson says. “If I don’t get the shot I don’t like, I just tell the subject, ‘Hold on for a second.’”

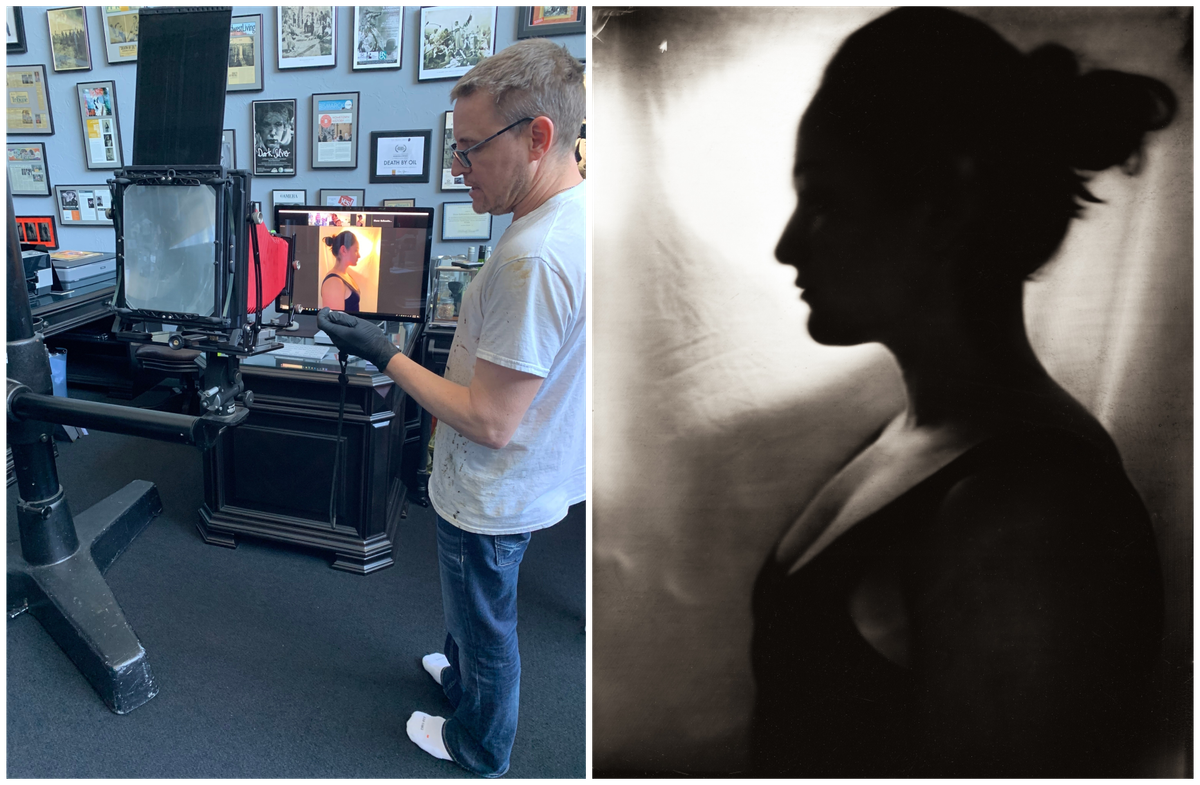

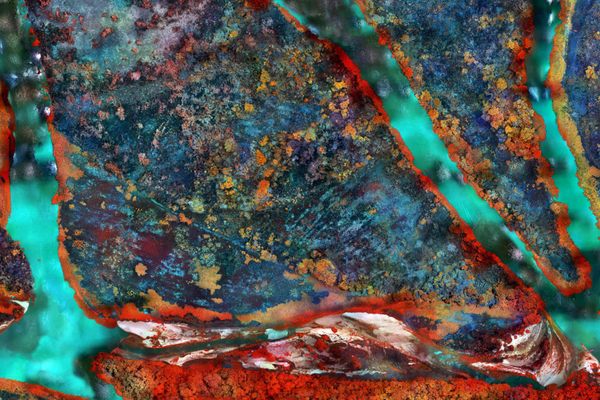

Shane Balkowitsch, a North Dakota-based wet plate photographer, also emphasizes the relationship with one’s subject. Recently, Balkowitsch shot a wet plate silhouette of a Zoom session in a long, 60-second exposure. It captured all of the movements of the model, Morgan Barbour, in a single image, from blinks to shallow breaths. “All of that is in those pictures,” Balkowitsch, who believes that even heartbeats are captured symbolically, says. “All that life is transferred from that person to that plate.”

Remote photoshoots can restore some of the camaraderie of photography while softening the loneliness of quarantine. They depict people who are physically isolated but socially connected. This is why Ngô decided not to turn to self portraits while in social isolation. “That would still be me working alone,” she says.

Before Anderson takes photos of her subjects, she talks to them about how they’re processing the pandemic and the changing world. “Sometimes the conversations are longer than shooting,” Anderson says. They talk about their worries, their cities, their families, and the difficulty of sustaining creative work. These conversations bridge the distance, at least for a time. “I’m in their home. They’re walking me around their house and apartment,” Anderson says. “It’s one of the most intimate photoshoots, and we’re doing it through a computer.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook