How Two Thieves Stole Thousands of Prints From University Libraries

They almost got away with it.

In the summer of 1980, Robert Kindred was a 35-year-old high school dropout with no plans of going to college. Despite that, scattered in the backseat of his newly leased Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham were half a dozen guides to American college and university locations, each representing a region of the United States. He also had a single volume covering the entire country in his briefcase. A former Boy Scout, he liked to be prepared.

No major American crime requires as much travelling as that of stealing rare books from libraries, a fact Kindred knew from experience. Thanks to wealthy Americans, poor Europeans, two hot wars, and one cold one, the fruits of 500 years of printing came to be scattered across the United States in the second half of the 20th century. And almost all of it could be found on the shelves of some college or university library.

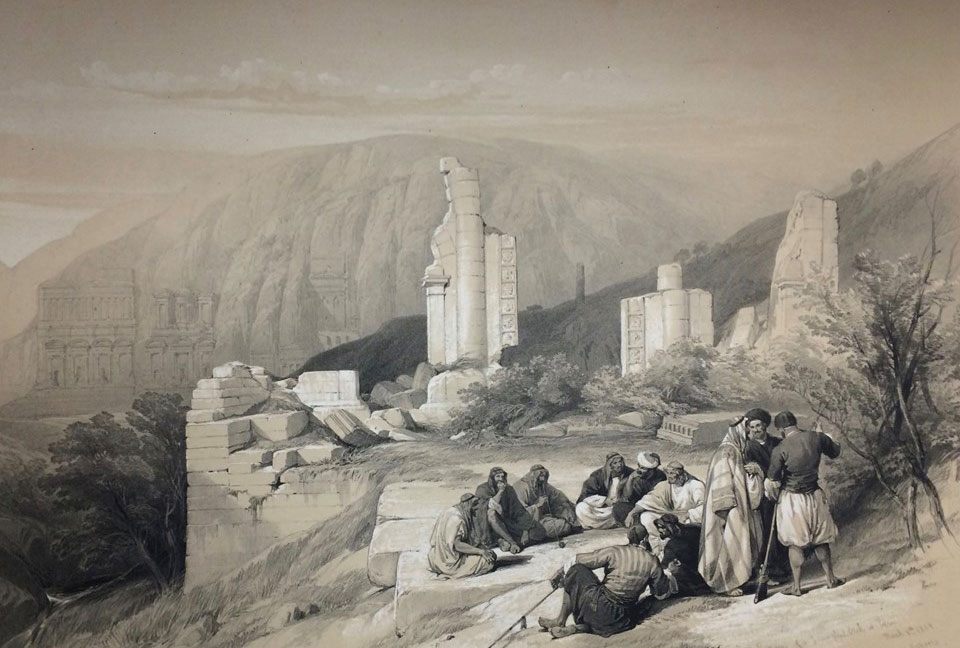

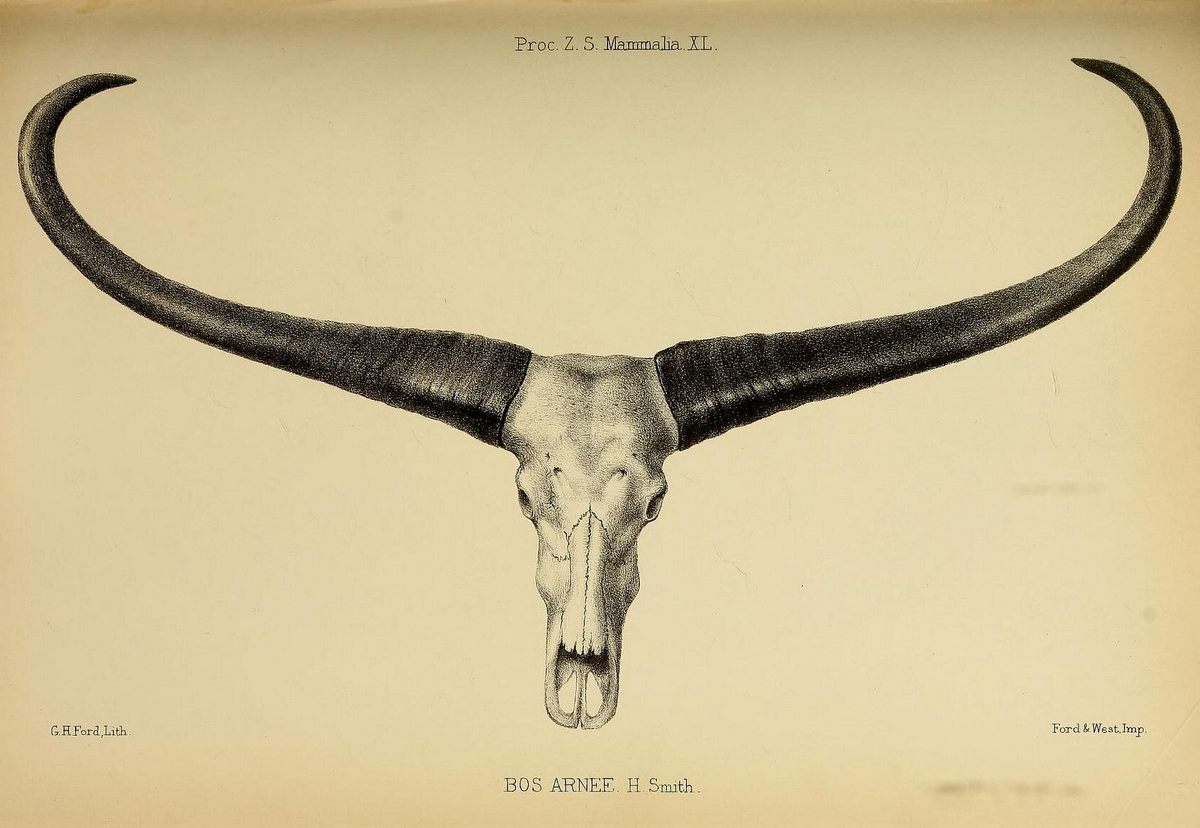

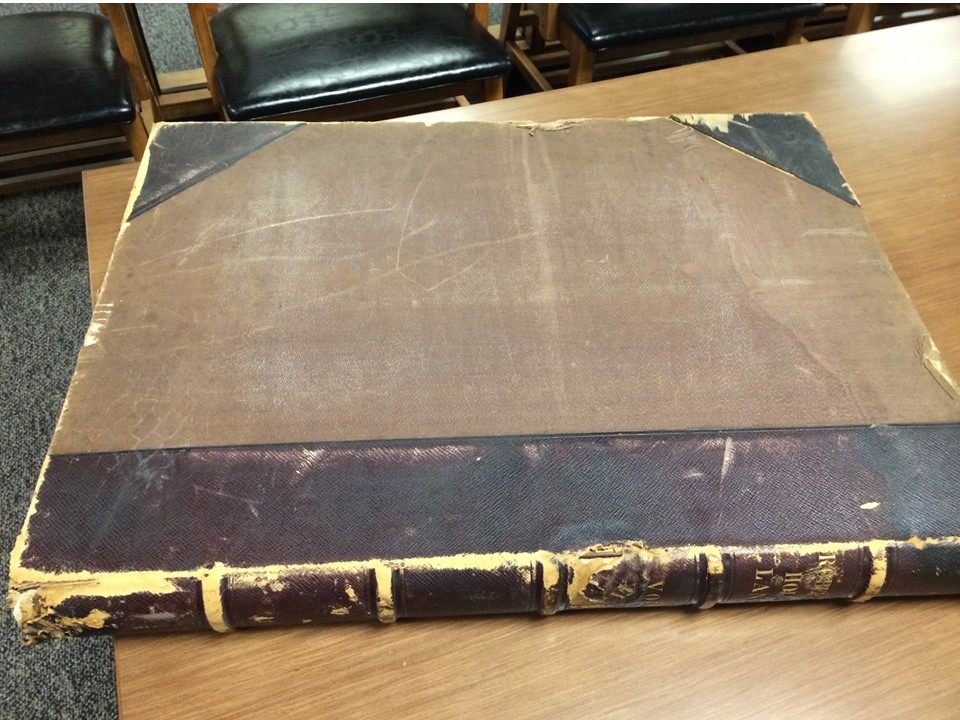

Of course, by the late 1970s, the most precious books and manuscripts in American collections had been put behind locked doors, libraries having learned that lesson the hard way. So Kindred, an antique print dealer, was not in the market for big ticket items, such as a Gutenberg Bible or Shakespeare First Folio. He was interested in the low hanging fruit of the rare book field: 19th-century scientific illustrations. In publications like Ibis and Ferns of North America and Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, the greatest natural history artists of the 19th century—including J.G. Keulemans and Joseph Wolf—had done their best work, contributing hand-colored lithographs and engravings of the world’s flora and fauna for the sake of science. Even after more than a century between the pages, the illustrations were as bright and vivid as the day they were created.

Kindred knew these books and journals were nearly impossible to find for sale, and prohibitively expensive even when they could be found. So for the sake of his business he turned to the open shelves of academic libraries. The irony is that the easy access granted him by libraries that summer was heir to the spirit of scientific inquiry in which these magnificent prints were created in the first place.

In addition to the college guides, Robert Kindred had a second important reference source in his car: a road atlas. On its largest map, he had circled a series of towns starting just south of Dallas, where he had a storefront. Linked by the Interstate Highway System, the circles went across the south, up the East Coast, and back through the Midwest. It looked like an oblong chain of pearls, clasped in north Texas.

The first circle on that map was College Station, home to Texas A&M University. The Evans Library there housed a world-class collection of 19th-century prints—but not for very much longer. Kindred and his partner Richard Green spent half a day and a handful of razors there, destroying one publication after another for the sake of their illustrations. In one afternoon they destroyed what had taken decades to gather and a century to create. The only thing left behind were the ghostly impressions on the pieces of tissue paper put between pages to preserve the illustrations—and the razors the two men dropped on the floor, dulled from use. The rest went into the hot trunk of the Cadillac, which they then pointed toward Houston, and Rice University.

At Rice their destruction was even worse. That school’s collection of 19th-century scientific illustration was more robust, for one, and the stacks more secluded. From Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London alone they cut out 1,300 prints. But quite beyond their favorites, the Rice collection was so impressive Kindred managed to find dozens of publications he had never seen before. Once he took them, no one at Rice would ever see them again.

After only two days, Kindred and Green had several thousand prints in their possession—enough inventory for several years, if Kindred wanted to turn back to Dallas. But their plan was to be on the road for several weeks, and open a new store in Washington, D.C. Plus, Kindred had already made those circles on the map. So the next day, the two men headed east, toward New Orleans, and Loyola University.

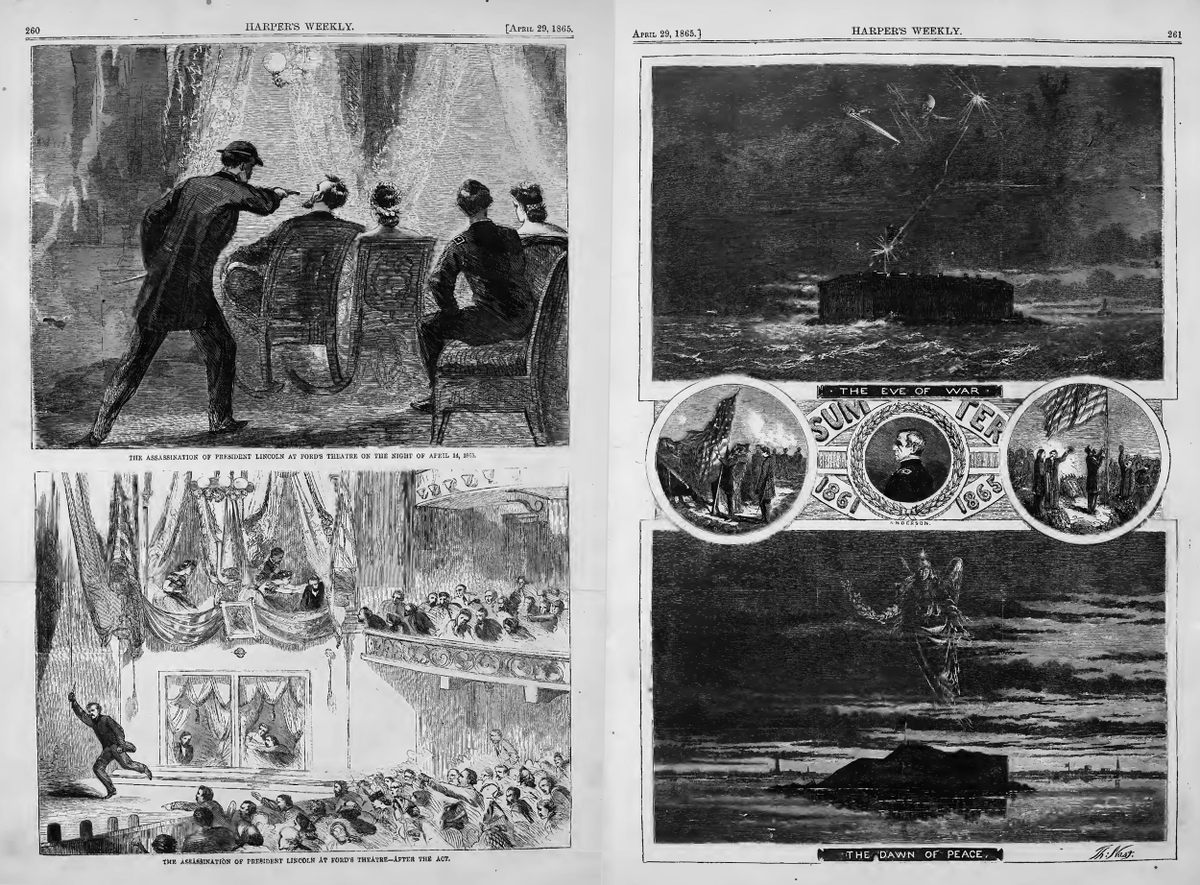

In fits and starts, the pair eventually made it to the nation’s capital. They lingered there for several days, while Kindred looked for a new storefront location, hitting the illustration collections of several local libraries along the way, most notably the University of Maryland, where the pair’s focus took a turn toward the strength of the collection, 19th-century news periodicals such as Harper’s Weekly and Illustrated London News. These were a nice change from natural history, offering a host of other types of illustrations, from ballerinas to baseball to battles of the Civil War. Then they pointed their big car west, toward what they thought was home, but was actually the end of their crime spree.

The third reference source Kindred kept with him was the Union List of Serials, a monumental work detailing the periodical holdings of more than a thousand U.S. libraries. It was the Union List that was most indispensable for the trip, as it was responsible for which towns got circled on his map. Kindred would look up his favorite publications and make a list of which universities owned them. If a certain university had enough of his favorites that it warranted a stop, he found its location in a college guide, called the library to find out its summer hours, and then circled it on the map. And that’s how the two men, weathered by weeks of travel and with a trunk full of stolen prints, decided to spend several days at the end of June in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois.

They would have stopped at the twin cities anyway—Kindred was from nearby, and had family in the area—but they would not have lingered. The prairie of east central Illinois has little scenic appeal in high summer, unless you’re into humidity and vistas of cash crops. But according to the Union List of Serials, the enormous University of Illinois library had nearly everything Kindred desired and a great deal more. What it did not have, however, was open stacks.

So instead of loitering in the library all day, cutting at their leisure as they had done everywhere else, Kindred and Green devised a different plan. Departing from a theretofore successful criminal formula would seem to most thieves to be a bad idea, especially if they were driving a car bursting with evidence of their prior success. But the theft of rare books from libraries has traditionally been so easy that it instills in even the least talented thief the idea that he is a criminal mastermind. So Kindred thought his plan was flawless. He broke in late at night, found a spot in the stacks with the largest concentration of books with prints, picked out his favorites, and then lowered them by rope out a window to Green below.

Unfortunately for him, the books he wanted were enormous, and located on the eighth floor. So gathering them in groups of four and lowering them down the side of the building was more heavy industry than cat burglary. Still, they made the plan work the first night and obtained some $10,000 in books. They were halfway through their second night when bad luck, for the first time in their trip, reared its head.

Once every five nights a university employee came to the large, deserted library in the middle of campus to check the air conditioning unit. Kindred had one packet of four books on the ground and another halfway down the side of the building when that employee swung his car into the parking lot, unaware he was about to put to an end the greatest theft spree of its kind in American history.

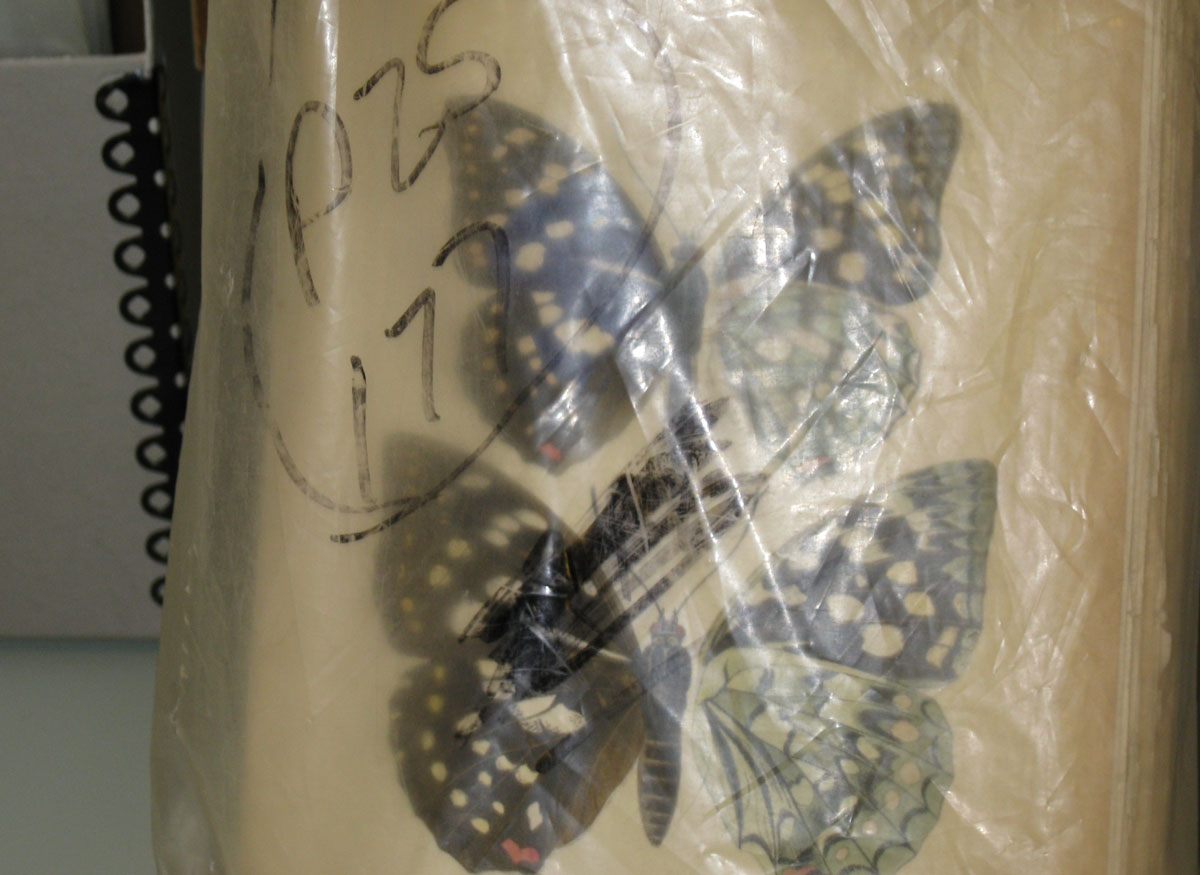

Kindred’s capture, and his subsequent prosecution, led to the creation of one more reference source, this one unique: a catalog of the stolen items he kept in the car trunk. Two librarians from the University of Illinois spent the rest of the summer of 1980 in a cramped room in the campus police station trying to make sense of the thousands of loose prints piled and packed in bags and boxes. Before web browsers and online catalogs—and without even access to a telephone to call other libraries—the two men mostly used their bibliographic instincts and a few reference sources to reverse engineer Kindred’s trip and identify the owners of some of the pieces.

Alas, all of their work amounted to nearly nothing. It aided the return of some of the prints to their rightful owners, but the state’s attorney did not use it at all. Kindred pleaded guilty to a single charge in Champaign County, and was sentenced to probation. Green was not prosecuted in Illinois at all, and neither man was prosecuted by any other state, including Texas, where they did the most damage.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook