Did German U-Boats Smuggle Alcohol Into the U.S. During Prohibition?

One photo suggests that rampant rumors of submarine smuggling were true.

In the winter of 1922, two years after the start of Prohibition in the United States, a mysterious craft was said to be sneaking around the waters of Seattle’s Puget Sound. Locals reported seeing the boat multiple times, and authorities believed that it had delivered illegal liquor in Seattle and then traveled south to the California coast. In years when the United States was a dry country—by law if not in practice—it was not uncommon for boats to smuggle liquor into the country. But this one was different. This one was a submarine.

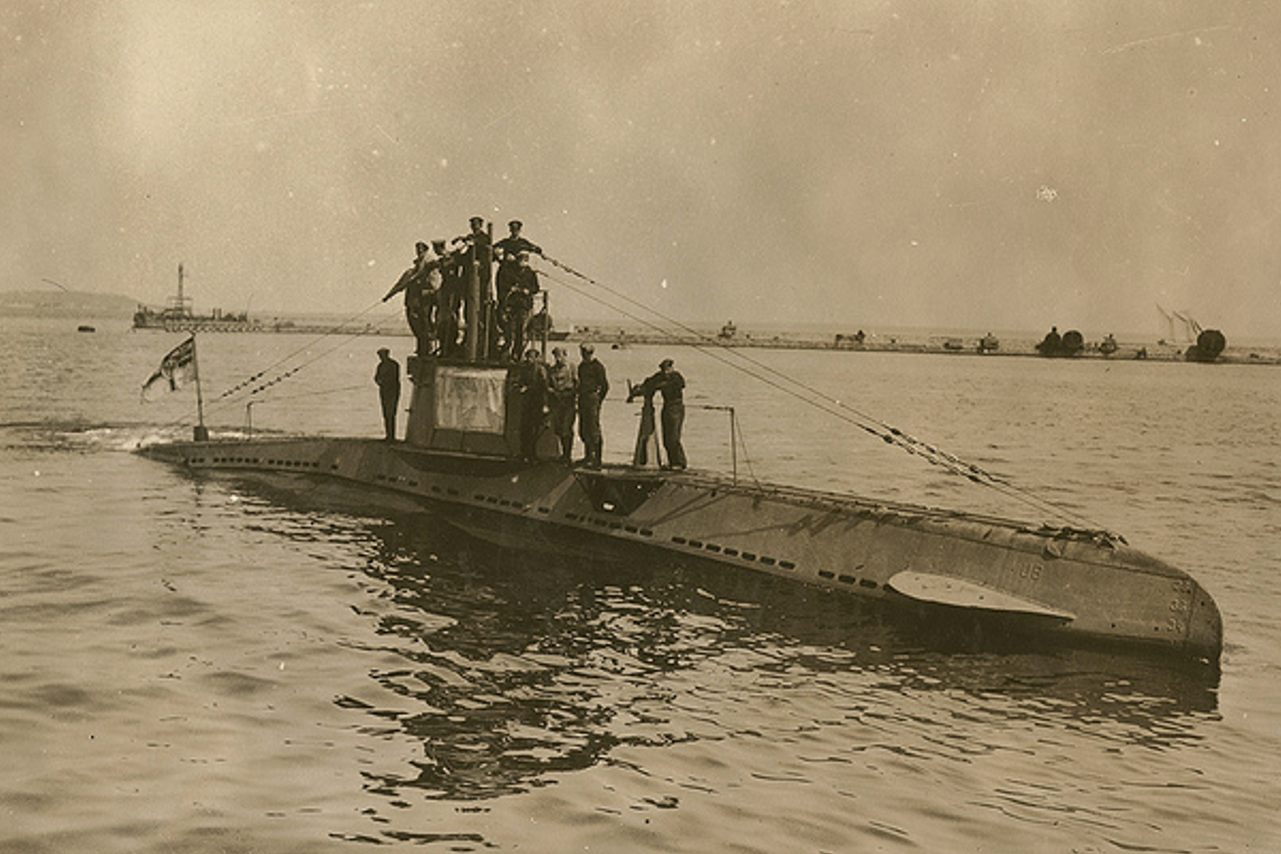

Submarines first became practical in the 1860s, when a crewed submarine successfully submerged, cruised, and resurfaced—and when, for the first time, a military submarine sank a ship. Several decades later, during World War I, submarines, specifically German U-boats, began to play a major strategic role for the first time. The creepy, claustrophobic craft had become the focus of public fascination and an enduring source of mystery and paranoia.

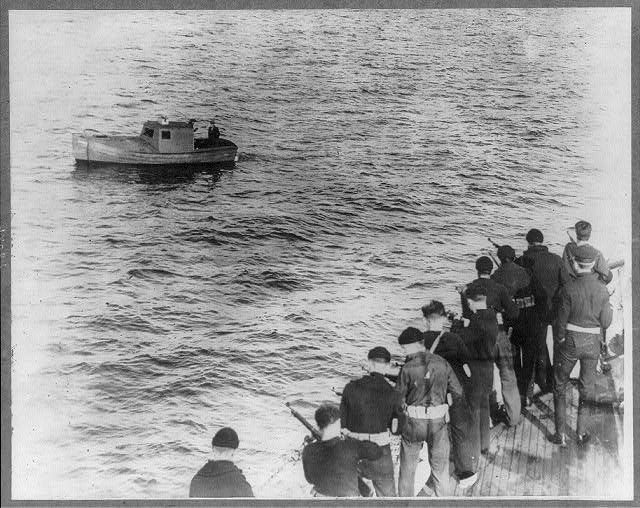

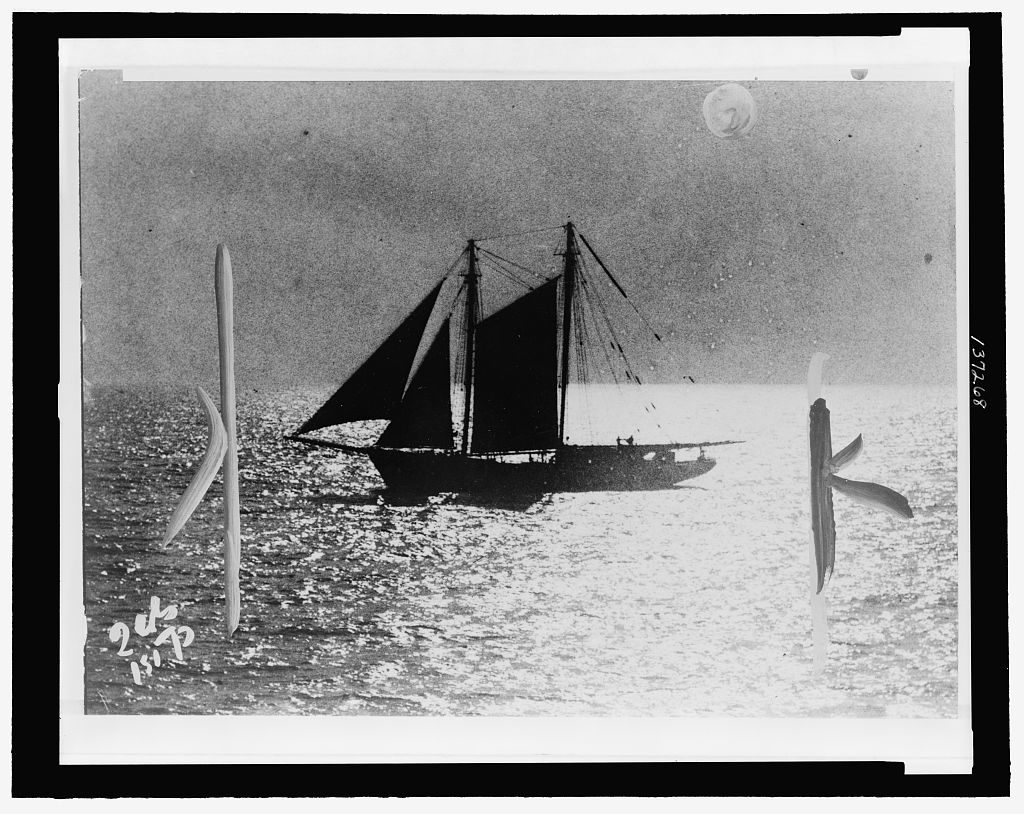

Throughout the Prohibition Era, there were persistent rumors and newspaper reports that boats—both traditional and the underwater variety—were running rum and other spirits from Canada and the Caribbean to thirsty American shores. Coastal officials investigated these sightings, but also tried to downplay submarine stories, calling them “absurd,” or reporting that what seemed to be submarine conning towers were, in fact, dorsal fins of dolphin.

But as much as U.S. officials wanted to deny it, there was at least some truth to the rumors of rumrunning submarines.

Around the same time as the reports of a submarine in Puget Sound began, East Coast officials were dealing with similar sightings—off the coast of Cape May, New Jersey, for example, where the Coast Guard faced wintry conditions to search for the alleged boat, the Associated Press reported at the time. Over the next few years, people began seeing smugglers’ submarines off the shore of Long Island all the way up to Cape Cod. Investigating officials, however, always came back empty-handed.

One of the reasons that authorities dismissed these reports is that it seemed unlikely that smugglers, even very successful ones, would have been able to obtain a submarine. They were still relatively rare: In the years before and during the war, Germany built close to 400 U-boats, but more than half were destroyed or out of commission by the end of the war. The United States had just a few dozen in total, with just 11 new subs constructed during the war. This was military technology that didn’t just fall into the hands of smugglers. Navy officials in New York told reporters that rumrunners would never get their hands on a submarine, “as the United States navy has sold none, and none is believed to have been manufactured in this country for other than war purposes under navy jurisdiction.”

People who claimed to have seen these boats were likely to agree with that assessment—because they didn’t think these were American Navy ships. The Puget Sound submarine was thought to have been built in Seattle but sold to the Canadian government, which later sold it for junk. And the boats on the East Coast were thought to come from Europe: “Up and down Cape Cod chin whiskers are bristling in the salt air as fishermen tell of a giant German U-boat which is torpedoing the Eighteenth Amendment with liquor and beer,” one United Press reporter wrote sun 1924.

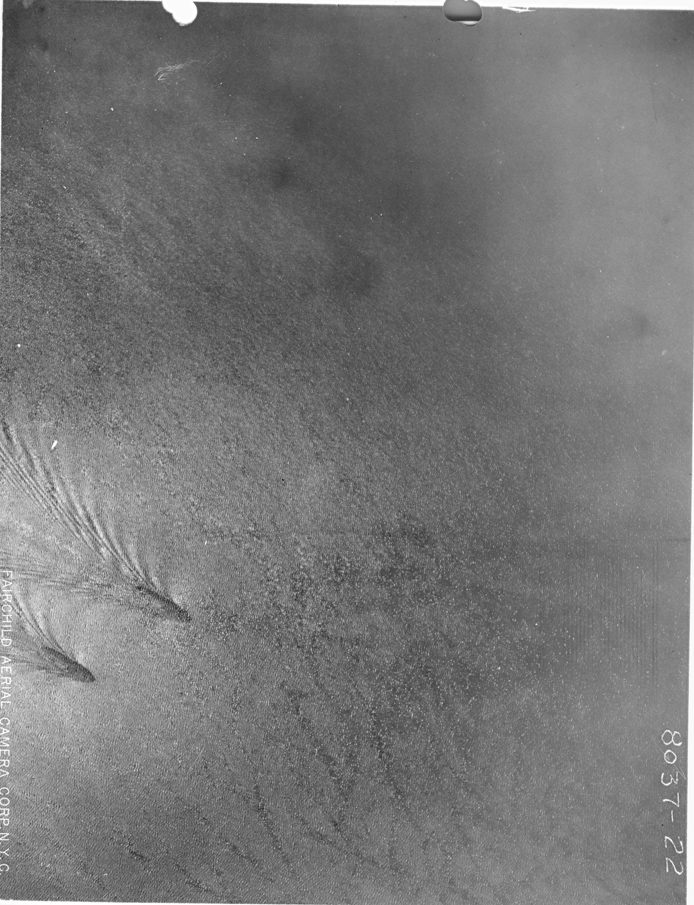

Finally, after two years of rumors, evidence surfaced. As historian Ellen NicKenzie Lawson reports in her book Smugglers, Bootleggers, And Scofflaws, in 1924, a commercial mapping firm was flying over the Hudson River when it spotted two submarines, each 250 feet long, in the water 30 miles up the river. They shared a photo with the Navy, which confirmed the submarines did not belong to the United States. Could those photos, preserved in Coast Guard intelligence files, have shown the U-boats of rumor?

Over the remaining years of Prohibition, law enforcement officials did sometimes find ingenious underwater craft used to ferry alcohol over international borders. In 1925, in Lake Michigan, smugglers were using a cast-iron craft, which the Associated Press described as a “cigar-shaped trailer” big enough to hold 150 cases of beer. The submerged iron case could be towed across the lake by boat. No one knows how many successful trips it made, but when officials found it, it had sprung a leak and sunk. The next year, Canadian authorities found a similar setup in Lake Champlain, which connects Quebec with New York and Vermont, a “submarine without motors” that could hold close to 5,000 bottles of beer. The beer weighed the container down to keep it underwater to be towed across the border.

This strategy seemed successful enough that variations were used (and sometimes foiled) through the 1930s (and it seems to be common in the drug trade today), but there’s no hard evidence of a U-boat running liquor on the East Coast or a rogue Canadian underwater vessel plying the waters of Puget Sound. If they had been out there, the same stealth that made them threats in wartime kept their party-time cargo safe.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook