Remembering America’s Golden Age of Hot Sodas

Drink like a Prohibition-era teen with recipes for the Hot Cherry Egg Bounce and Hot Egg Lime Juice Fizz.

In the classic American play Our Town, Emily Webb and George Gibbs stop at Mr. Morgan’s drug store. There, at the soda fountain that serves as the center of the social life in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, young love blossoms over strawberry ice-cream sodas: Emily and George realize they are “fond of” each other and always will be.

The play is set in 1901 and debuted in 1938, when soda fountains had become wildly popular. They were in drug stores and department stores, on steamships and trains. According to a 1929 issue of The New York Times, Americans were spending $700 million annually at soda fountains. Emily and George’s youthful romance was far from the only one set among ice-cream sodas. In one memorable scene from the film It’s a Wonderful Life, a young George Bailey scoops ice cream behind the counter as Mary Hatch whispers softly, “George Bailey, I’ll love you till the day I die.”

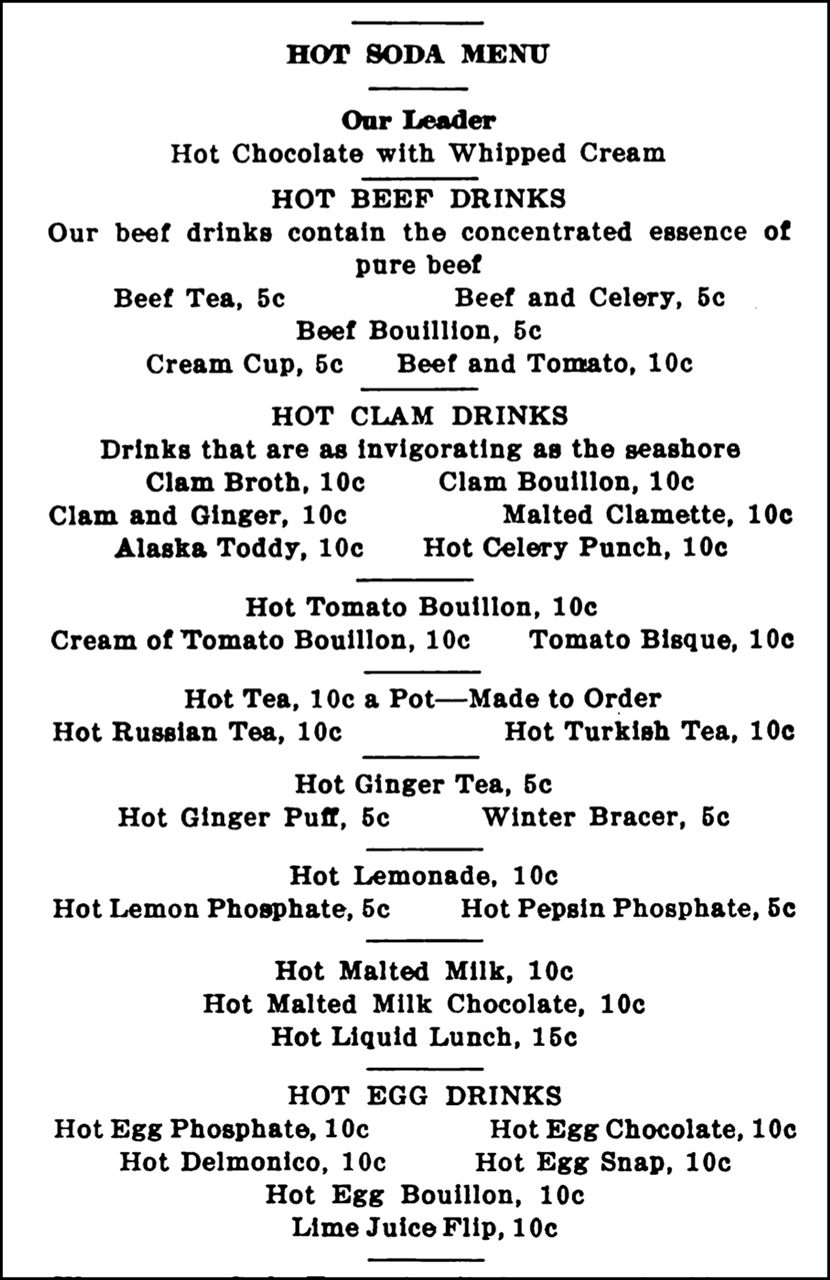

But the gargantuan soda-fountain industry had a problem: Every year, as soon as the temperature dipped, sales and profits did too. So each winter, soda fountains recommended what they called “hot sodas,” which could mean anything from hot eggnog to hot mint juleps to a “Reeking Smatch” (a blend of clam juice, cream, and ginger). Although largely forgotten, the appearance of these drinks heralded the start of a new season in the United States just as the pumpkin spice latte does today.

Not all the wintertime drinks were sodas. Some were simply familiar drinks such as coffee, tea, or hot chocolate topped with whipped cream. Soups and broths served in cups and sipped were also called hot sodas. Other drinks, such as hot angostura tonic and hot pepsin phosphate, recalled soda fountains’ medicinal roots in 19th-century drug stores. These early fountains dispensed carbonated waters and drinks including C.O. Cocktails (castor oil and soda), celery caffeine bromide, and “Moxie Nerve Food” to middle-aged men suffering from upset stomachs, nervous exhaustion, or other conditions. Similarly, Coca-Cola treated headaches and depression and Dr Pepper was sold as a “brain food and exhilarate.” Only after the replacement of old elixirs with modern medicines, and the influence of the temperance movement and Prohibition, did bicarbonate of soda and Bromo Caffeine give way to the strawberry flip, the orange fizz, the ice cream soda, and the sundae.

Hot drinks became popular almost immediately, especially with women. A New York Times column in March 1902, which referred to a drugstore fountain in the city as the “Woman’s free lunch counter,” was typical. Every day at noon, women arrived and ordered a beverage, “usually hot,” according to the article, which noted that the women were partial to hot-egg drinks. Because the hot drinks were accompanied by crackers, they were “equal to a small meal in themselves.” The drugstore, unnamed in the article but located in the heart of the shopping district, was said to be selling so many hot drinks that they needed to upgrade from a two-gallon boiler to a 40-gallon one.

Hot-egg drinks were not the only popular choice. Soda fountains sold hot ginger ale and other sodas, which didn’t come from bottles or cans, but were made in-house from the fountain’s own syrups or extracts. They simply added cold soda water for cold sodas and hot water for hot ones. The October 1918 issue of Confectioners’ Gazette included this recipe for hot ginger ale:

Soluble ginger ale extract, 10 drops; soluble lemon extract, 10 drops; sugar, two cubes (or teaspoonfuls); fruit acid, 10 drops; hot water to fill the mug.

Popular drinks called phosphates, meanwhile, were made with “fruit acid” or “acid phosphate.” The acids added a dry, sour element, like lemon or lime juice, but without the specific taste of the fruit. They’ve become popular in cocktails today, but they were especially helpful back then since citrus fruits were less available and more expensive. A 1921 issue of The Spatula magazine ran this recipe for Hot Foam Phosphate below the heading New Hot Drinks:

Pour one-half ounce of orange syrup and one-half ounce of lemon syrup into a cup containing one egg well beaten. Add a dash of acid phosphate and fill with hot water. Finish with a pinch of nutmeg.

The popularity of hot drinks didn’t happen on its own. Trade magazines and books not only published recipes, which they often called formulas, for everything from hot pineapple juice to hot malted orange, but they also offered promotional ideas and sales tips. An issue of The Soda Fountain, for example, suggested staging a “Hot Soda Pageant This Winter.” The editors proposed selecting different drinks each month and promoting them with window displays. One month would promote hot milk and egg drinks; another bouillons, broths, and soups; another coffee, tea, and chocolate drinks; another hot fruit drinks. During malted-milk-drinks months, they recommended a “peaceful scene with cows grazing, milkmaids, great pails of foaming milk and happy, healthy youngsters in the foreground.”

In a fall issue of The Confectioners Journal, the magazine ran a column of “Hot Soda Hints” filled with practical advice like:

“Never use silver cups for hot soda. They hold the heat and will burn the lips. China will not.”

“Never serve a straw with a hot drink.”

“Always serve a drink too hot… if you serve [a customer] a luke-warm drink he will never come back again.”

They also listed presentation tips:

“Use whipped cream on every possible hot drink. It costs but little and makes it classy.”

“Serve sweet crackers with sweet drinks like chocolate and coffee; saltines with the bouillons. They match better that way.”

“Have sugar, pepper, salt, celery salt, grated nutmeg, and Worcester sauce handy so a customer may season his drink to suit his taste.”

Best of all:

“Introduce some novelty at your hot soda counter every week. It keeps interest awake—yours and the customer’s.”

The Confectioners Journal’s prediction came true. Serving hot sodas and crackers led naturally to the addition of sandwiches and soups, especially when Prohibition ended the barroom tradition of a free lunch with a drink. Before long, for both men and women, having lunch at the soda fountain was as natural as having a soda.

In a 1930 New York Times article titled “The Human Filling Station,” Eunice Fuller Barnard wrote, “Three meals a day, once a function of hearth and home, and lately of kitchenette and restaurant, are passing before our unconsidering gaze to the nickeled and marbled purlieus of the soda fountain. Where a decade ago it purveyed a few timid crackers along with the hot chocolate, today there is little from chowder to pie, or from waffles to chop suey, that is not at one time or another in its enterprising repertoire.” She attributed this to Prohibition, the speed of modern life, convenience, and affordability. She failed to mention the lengths the fountain business went in order to make sure their industry grew and succeeded, in hot weather and cold.

Today, nearly all of the drug-store soda fountains have been replaced by fast-food chains, and hot ginger ale isn’t on menus. But there’s no reason we can’t follow one of these recipes and enjoy our own hot sodas.

Hot Cherry Egg Bounce

From The Dispenser Soda Water Guide, c 1909

One egg, 2 ounces cherry juice, 1 spoonful powdered sugar. Mix thoroughly and mix again while adding hot water. Add several cherries and a slice of orange. Serve with nutmeg.

Tasting Notes:

- Taste the drink after adding the hot water and adjust the amount of cherry juice and sugar as necessary to get a pleasant sweet-tart flavor.

- Canned, pitted cherries work wonderfully for this recipe. If using them, their syrup can be added to the drink or substituted for the sugar for an extra cherry kick.

Hot Egg Lime Juice Fizz

From The Dispenser Soda Water Guide, c 1909

White of 1 egg, 1 ounce lime juice, 2 teaspoonfuls powdered sugar. Add hot water and top off with a small spoonful of whipped cream.

Tasting notes:

- Microwave your lime for 20 seconds first to make it easier to squeeze and get the most juice out of the fruit. (The heat softens the membranes of the fruit, and your drink will be hot anyway!)

- 1 large lime produces about 1 oz of juice.

- Grate a bit of lime on top of the whipped cream for a final zesty flourish.

- Add hot water slowly while stirring with a fork to avoid cooking the egg white too much.

- If you prefer your sodas sweeter, you may prefer 1-2 tbsp of powdered sugar rather than the 2 tsp stated in the recipe.

Reeking Smatch

From The Dispenser Soda Water Guide, c 1909

Cream, 1 ounce; clam juice, 1 ounce; butter, 1 teaspoonful; Jamaica ginger extract, 1 teaspoonful. Place in mug, fill with hot water, and season with celery salt.

Tasting notes:

- If you don’t have easy access to clam juice, you can make your own with fresh clams. Add a few clams to a mug, just barely cover with hot water, and microwave for 1-2 minutes, until the shells have opened and the clams are fully boiled. Remove the clams and stir up the resulting clam juice.

- Don’t hold back on the ginger extract! The kick it adds is key to balancing the flavor.

Grace Kwan contributed recipe testing to this story.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook