The Power of a South Pole Sunrise After Six Months of Darkness

Astrophysicist Robert Schwarz has spent more winters at the southern tip of the world than any human in history.

On September 20, the sun began to rise at the South Pole. It took 30 hours for the sun’s disk to clear the horizon, and weeks later, it is still climbing toward noon. And for the first time in a decade, Robert Schwarz, a.k.a. The Iceman, was not there to see it. “When the sun started coming up, I always thought it was too bad,” Schwarz says. “It means winter at the South Pole is ending.”

Antarctic weather is notoriously bad, so this year’s sunrise wasn’t much to see. But staff at the South Pole say they still laugh with surprise when they step outside into the golden light gleaming off the ice.

In the heart of Antarctica, winter is one long night that lasts six months. As darkness starts to fall in mid-February of each year, a small crowd gathers outside Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station to watch a gray C-130 Hercules ski down an icy airstrip and take off. Because no planes brave the sunless Antarctic winter, this flight is the last chance to leave the white continent. Everyone who stays is stuck there until the summer research season starts in November. Antarcticans call it “wintering over.”

Schwarz has spent 15 winters at the South Pole, nine of them in succession from 2011 to 2019. When he stepped down from his role this year at the age of 50, he had wintered over at “Pole,” as it is colloquially known, more times than any human in history. On a recent Friday, he was at home in Germany, wearing a yellow shirt emblazoned with the word “ANTARCTICA.” He smiled often and laughed easily. On the wall behind him, a framed poster showed Neil Armstrong standing on the Moon.

The COVID-19 pandemic isn’t exactly what Schwarz had in mind for his first year back from Antarctica, but he has learned a few things from the isolation of winter at the Pole. “I finally have time for all the projects I missed out on over the last 10 years,” he says. “You have to make the best of it.”

Denis Barkats, a senior scientist who wintered with Schwarz in 2006, recalls an old Antarctic joke: “The first time you winter, it’s for the adventure. The second time, it’s for the money. The third time, it’s because you don’t fit anywhere else.” But that doesn’t seem true of Schwarz, who is cheerful and easygoing, Barkats says. “He has something I don’t have,” he goes on. To return 15 times, one must effectively treat the rigors of winter as one’s job. “You might say, ‘Oh boy, I really want a watermelon!,’” Barkats says with a smile. “Well, you can’t have it for nine months.”

Schwarz doesn’t regard himself as unusual. Still, at the start of each winter, as Pole’s summer population fell from around 150 to under 50, he usually felt relief. “Suddenly everything is quiet, you only hear the wind, and there are only a few people left,” he says. “It’s a great feeling.”

For weeks, the small crew watches the sun spiral closer to the icy plateau. (At Pole, one can literally see the Earth orbiting the Sun.) In late March, the sun finally touches the horizon. As it disappears over the course of a full day, it emits an elusive “green flash” rarely seen anywhere else in the world. For the month that follows, twilight slowly fades and the world seems to shrink in every direction but one: upward.

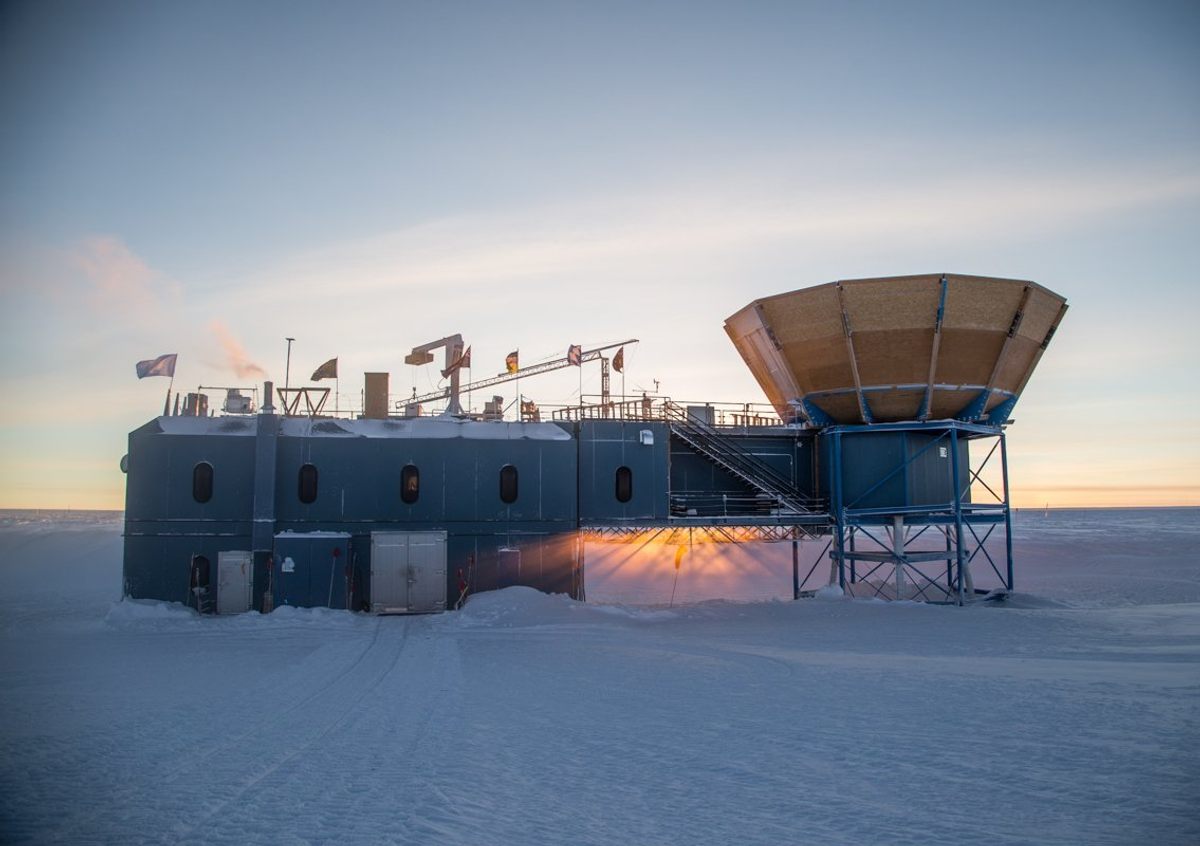

Most research at the South Pole is directed into outer space, and during winter, Schwarz’s job was to look after telescopes. One area, known as the “Dark Sector,” is kept free of light and electromagnetic signals, and houses some of the world’s largest telescopes. Here, in the clearest air in the world, the telescopes look back in time, to the Big Bang and the origins of the universe. “When we look into space, we always look into the past,” Schwarz says. “And the signal we are looking at was 13.8 billion years on its way to us.”

Schwarz holds an advanced degree in physics and astronomy, but describes himself as a “soldering iron and wrench physicist.” He has done everything from maintaining hardware to debugging software to cryogenics—whatever the telescope needs to continue beaming data out to researchers. “If something breaks, you can’t order new parts,” Schwarz points out. “Well, you can, but they won’t arrive until summer. You have to start improvising.” He considers it a bit like living on another planet.

The history of Antarctic winter-overs is full of grim stories: mental breakdowns, even attempted murders. The Belgian explorers who were first to overwinter on the continent developed a therapeutic routine of walking in endless circles around their ship, the Belgica, which became trapped in the ice in 1899. They called it the “madhouse promenade.”

These days, those who overwinter at Pole bid farewell to the last flight by watching all three versions of The Thing, about an Antarctic station crew torn apart by paranoia and an alien invader. (They used to watch Kubrick’s The Shining, but now they save that for midwinter.) “People who are curious have a great time,” Schwarz says. “It doesn’t matter if you have a PhD, if you’re a cook, if you’re a mechanic—everybody’s equal.”

The winter crew try to keep busy, filling their social calendars with parties, pickup basketball, and movie screenings. “One of the doctors I wintered with three times taught us how to assist during surgery,” Schwarz says. And when the temperature drops to 100 degrees below zero, you can join the exclusive “300 Club” by jogging naked from a 200° F sauna to the South Pole marker and back. Naturally, Schwarz has joined several times over.

Paula Crock, a telescope engineer currently wintering at Pole, agrees that it helps to stay curious and open-minded. “I’ve learned not to get fixated on thoughts of what I am missing up north,” she writes via email from Antarctica, “but instead focus on the opportunities that I have down here.” She has self-care rituals, too: sleeping in sometimes, having some ice cream at night. “It’s important to not take it personally if one of your crewmates is having a bad day, and forgive and forget easily if they take it out on you,” Crock says.

Of everything he experienced at Pole, Schwarz misses the aurora australis, or southern lights, most of all. Every day, he would walk 15 minutes from the main station building to the Dark Sector.* On his “commute,” Schwarz would listen to the crunch of his boots on the frozen ground and the wind passing over the polar plateau. “Sometimes you’ll walk and see the snow flashing green,” he recalls, “and you’ll look up and see this awesome aurora display above you.”

The river-like flow of an aurora is formed by bursts of charged particles from the sun. When these “solar storms” strike the Earth’s protective magnetic field, the collision releases energy in a dazzling array of colors that stream towards the poles. “A rule of thumb is the brighter they are, the faster they move, and they can move really, really fast,” Schwarz says. “The auroras alone are worth going there for.”

Outside of Antarctica, Schwarz actually considers himself a summer person. “Back home, six months, no sun? It would be crazy, I can’t imagine it,” he says with a laugh. “But at Pole, things are in many respects so different. I actually enjoy the real darkness there.”

After spending a quarter of his life in Antarctica, living in Germany has taken some adjusting. His email signoff still reads: “Antarctica - best place on Earth.” Unable to travel far due to pandemic restrictions, he is exploring the mountains close to home, and even found a bit of astronomy at a nearby museum: the Nebra Sky Disk, an ancient bronze map of the heavens. “You have to live with what you have,” he says. “When things come back, you’ll enjoy them even more.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this piece described the walk from the main station building to Dark Sector taking 30 minutes.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook