Taiwan’s Pygmy Seahorses Have a Robust Social Media Presence

Scientists used it to conduct a survey of them in the country’s dive hotspots.

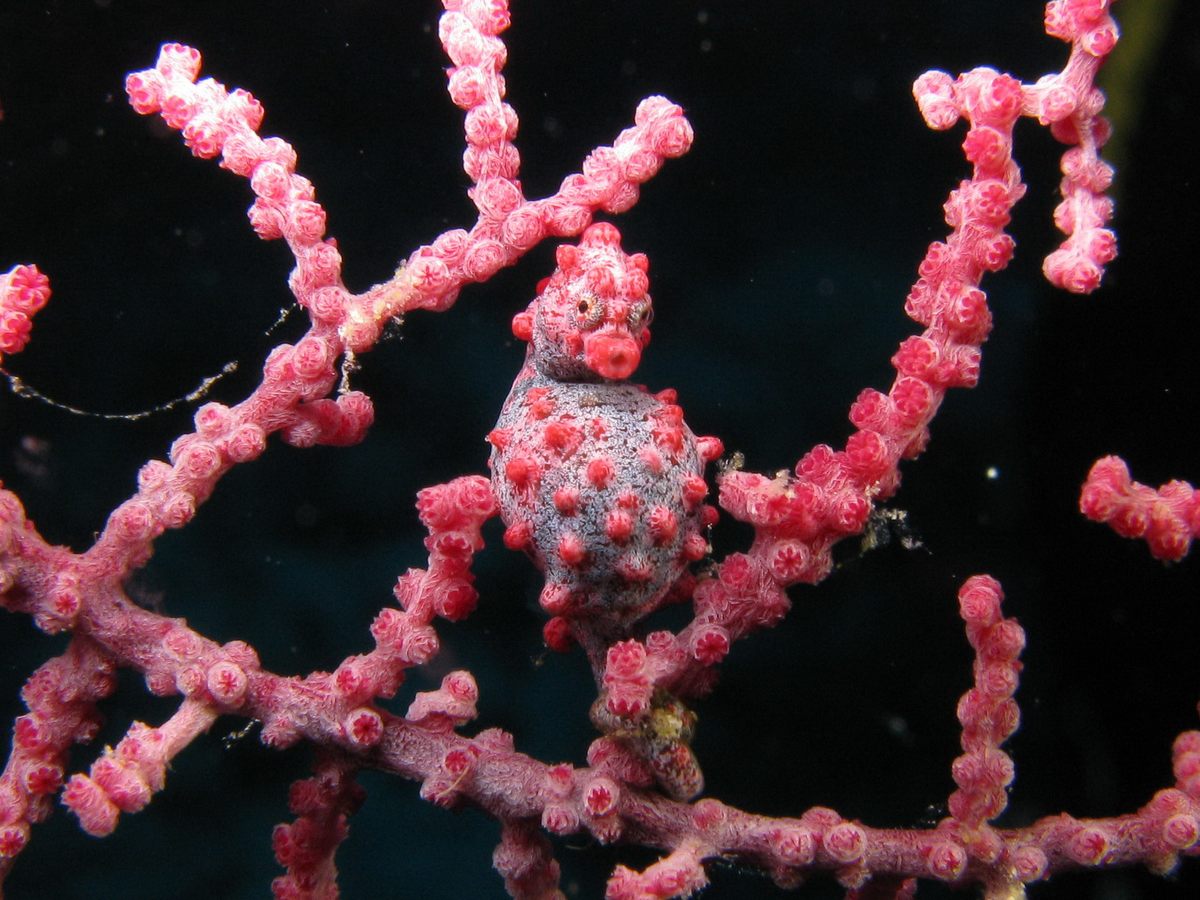

Joseph Heard had journeyed to Orchid Island to find a seahorse the size of a paperclip. Typhoon season had just passed in 2019, and a diver had reported spotting a single female pygmy seahorse—Denise’s pygmy seahorse, Hippocampus denise, specifically—coiled around a gorgonian sea fan off the coast of the Taiwanese island, almost 100 feet below the surface. Marine biologist Heard and his team of divers located the sea fan—it wasn’t terribly hard, as it was only one in the area, right next to a drop-off—and looked for at least 10 minutes, examining every latticed crevice of the nearly 10-foot-tall soft coral. There was no tiny seahorse, but instead a hawkfish, one of H. denise’s known predators. Mystery solved.

This might be a pygmy seahorse researcher’s greatest challenge: finding them in the first place. “You can spend hours and come back with nothing,” says Heard, from Tunghai University in Taiwan. “I never want to have my hopes up.” It’s not just that pygmy seahorses are small—and they are itty-bitty—but also that they’re aces at camouflage. That can make it impossible for any one person to document the critters alone, so the few scientists who study them often rely on social media. People know that pygmy seahorses lurk in the waters near Taiwan, and divers that spot them often take pictures. So Heard and Colin Wen, another marine biologist at Tunghai University, used social media to complete the first-ever survey of Taiwan’s known populations of pygmy seahorses. They found that the waters boast enough distinct species to be considered a biodiversity hotspot. Their study was published recently in the journal ZooKeys.

Heard and Wen first came up with the idea for the survey while studying something much larger: schools of fish such as milkfish and sea breams. But the ocean is a big place and, like the seahorses, the fish proved surprisingly hard to spot—for a reason. “We were collecting data to prove that parts of Taiwan are being overfished,” Wen says. So in their downtime, the biologists began looking for other, more cryptic, species. That’s when they learned from the scuba community about the H. denise sighting. Heard wanted to find it.

Pygmy seahorses, which rarely grow over an inch long, can spend their entire lives on a single coral colony. Some species, such as Denise’s seahorse, live exclusively on one or two species of sea fans, and have evolved to match their coloration and texture to them exactly. Scientists only discovered the first pygmy seahorse, Bargibant’s pygmy seahorse, H. bargibanti, because one turned up on a sea fan that wound up on a dissection table in New Caledonia in 1969.

With no Denise’s seahorse, Heard and Wen had nothing to report. So they set themselves on a data set larger than a single individual of a single species, and considered how they might create a distribution map of all of Taiwan’s pygmy seahorses. “All pygmy seahorse distribution data to date is based on haphazard sightings here and there,” Wen says. “If one person sees a pygmy seahorse in one country, that becomes a population.”

Since they were unable to find even one, the scientists figured they’d have to enlist an army—and there are a lot of divers who frequent the waters around Taiwan and its smaller islands in the western Pacific. They pored through posts on Facebook and Instagram, between 2017 and 2019, that included the term “豆丁海馬”—Chinese for “pygmy seahorse.” They also dug into underwater photography message boards. “I constantly scour underwater photography websites and social media to see if any unusual fishes have been observed and photographed by local divers,” Graham Short, an ichthyologist at the California Academy of Sciences who was not involved in the survey, writes in an email. “Thank god for Google Translate!”

According to Heard, there’s a fine, fine line between regular seahorses, which are small, and pygmy seahorses, which are really small (and dwarf seahorses, which are tiny regular seahorses). Aside from size, pygmy seahorses have a single gill slit opening and trunk brooding, compared with a pair of gills and pouch brooding in the others. Some species are mistaken for pygmies, such as the paradoxical seahorse and the bullneck seahorse, which are both actually dwarf seahorses. Luckily, the diving community knows its hippocamps; the majority of the social media posts did not make this mistake.

From 75 photos and 275 social media posts of professional and amateur divers, the researchers identified 78 individual animals and triangulated where they might live. The photos also confirmed that there are five species of pygmy seahorses living in Taiwanese waters: Bargibant’s, Denise’s, Coleman’s (H. colemani), Pontoh’s (H. pontohi), and the Japanese pygmy seahorse, or H. japapigu, which was discovered just last year.

The Japanese species had only ever been recorded in southern Japan. In 2017, a diver saw a cluster of seven of them off the coast of Hejie, Taiwan, clustered in halimeda algae—a throng, by pygmy standards. H. japapigu is found in the lower reaches of the Kuroshio Current, Hiroyuki Motomura, an ichthyologist at Kagoshima University who helped discovered the species, writes in an email. Taiwan is at one end of the current, explaining how something so small might have a range that could span over a thousand miles of ocean.

As the researchers collected data and photos of the striking creatures, Heard grew determined to see them in Taiwan himself. Orchid Island was a bust. In one area, Heard and two other divers spent three hours peeking inside every nook and cranny of a rock. Later that month, Heard tried Green Island, on the basis of social posts by the owner of a local dive shop. It took an hour and a half, but he finally found one: a single individual in a clump of algae. “He was larger than I expected,” Heard says. “Which is to say, not very big at all.”

Heard tried to take a photo, but “He was being really uncooperative. Every time we took a photo, it would turn away.” Eventually they got the snap and collected the specimen for study. “Coral people, whenever they find a new species it just sits there for them!” Heard says. “I’m jealous.”

Though Heard originally identified the specimen as a Coleman’s, he’s found a few traits that don’t quite fit. “The coloration is a bit different, and the shape of the coronet is short,” he says, referring to the group of spines that crest the seahorse’s head like a mohawk. Genetics and CT scans are next. Until then, the critter is in Heard’s fridge, almost impossible to see in a small bottle.

For all these reasons, very little is known about pygmy seahorses, Heard says. No one has managed to keep one alive in a lab, but for now, the researchers hope their distribution map, though far from exhaustive, will help guide development along Taiwan’s coast, Wen says. “The first step to conserving a species is knowing where they occur in your country,” he says. “There are still so many species that are undiscovered.” Green Island has already begun to adopt its tiny stars: Photos of the animals decorate storefronts and a children’s book. The photos are, needless to say, larger than life.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook